- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

L’Assemblée dans un parc

Entered August 2015; revised November 2022

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. MI 1124.

Oil on walnut panel (additional strips of poplar or tilleul)

32.3 x 46.2 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Assembly in a Park

Convegno in un parco

Gathering in a Park with a Flautist

Gesellschaft im Park

Paÿsage avec figures en parc

PROVENANCE

Owned by Jules Robert de Cotte (d. 1767; director of the monnaie des médailles); by descent to his grand daughter. Sold to Dr. Louis La Caze.

Paris, collection of Dr. Louis La Caze (1798-1869; physician). “Etat des tableaux de la collection La Caze, (ms.)” cat. 76: “Assemblée dans un parc (gravé par Aveline) délicieux tableau —.” On the verso of the painting is La Caze’s label: “paÿsage avec figures en parc de Wateau aÿant appartenu a Mr de Cotte directeur des médailles de la monnaÿe vendu par sa niece Mde de Cotte son heritiere rüe de Varenne no 36 a paris connû comme un des plus fin de ce maitre. gravé par avaline.”

The La Caze family donated the painting to the Louvre in 1869.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, musée du Louvre, Chefs d’oeuvre (1945), cat. 123 (as Watteau, Assemblée dans un parc, lent by the musée du Louvre).

Paris, Petit palais, Chefs d’oeuvre de la peinture française (1946), cat. 205 (as Watteau, Assemblée dans un parc, lent by the musée du Louvre).

San Francisco, Palace of the Legion of Honor, Exhibition of French Art (1949).

Rome, Ames et visages de France (1962).

Vienna, Oberes Belvedere, Kunst und Geist Frankreichs im 18 Jahrhundert (1966), cat. 76 (as Watteau, Gesellschaft im Park, lent by Musée du Louvre).

San Diego, Fine Arts Gallery, French Paintings (1967), (as Watteau, Gathering in a Park, lent by the musée du Louvre).

Paris, Monnaie, Pélerinage (1977), cat. 38 (as Watteau, Assemblée dans un parc, lent by the musée du Louvre).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 56 (as by Watteau, Assembly in a Park / Assemblée dans un parc, lent by the musée du Louvre).

Paris, Louvre, Les Donateurs du Louvre (1989).

Valenciennes, Musée des beaux-arts, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), cat. 44.

Louvre, Le tableau du mois no. 109, (1984).

Paris, Louvre, Collection La Caze (2007), 195.

Paris, Louvre, L’Envers du tableau (2011), cat. 22.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Paris, Louvre, Notice des tableaux (1870), cat. 263.

Goncourt, Watteau (1875), 165.

Paris, Louvre, Catalogue sommaire des peintures (1903), cat. 986.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), no. 45.

Brière, Louvre, catalogue de peintures (1924), cat. 986.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 2: 99.

Wildenstein, Lancret (1924), n. 136 and 276.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 149.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1930), 30-31.

Ratouis de Limay, “Trois collectioneurs“ (1938), 78.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 186.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 35, 68.

Brookner, Watteau (1967), pl. 24.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 170.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A26.

Rosenberg, Reynaud, and Compin, Musée du Louvre, Catalogue (1974), cat 922.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 211.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 111, 176.

Compin and Roquebert, Catalogue sommaire (1986), 286.

Jollet, Watteau (1994), pl. 44.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 466, 504, 506, 536, 543, 553, G5, G68, G78.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 91, cat. 83.

Techné, Watteau et la fête galante (2010), 17, 103-04.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 146.

RELATED DRAWINGS

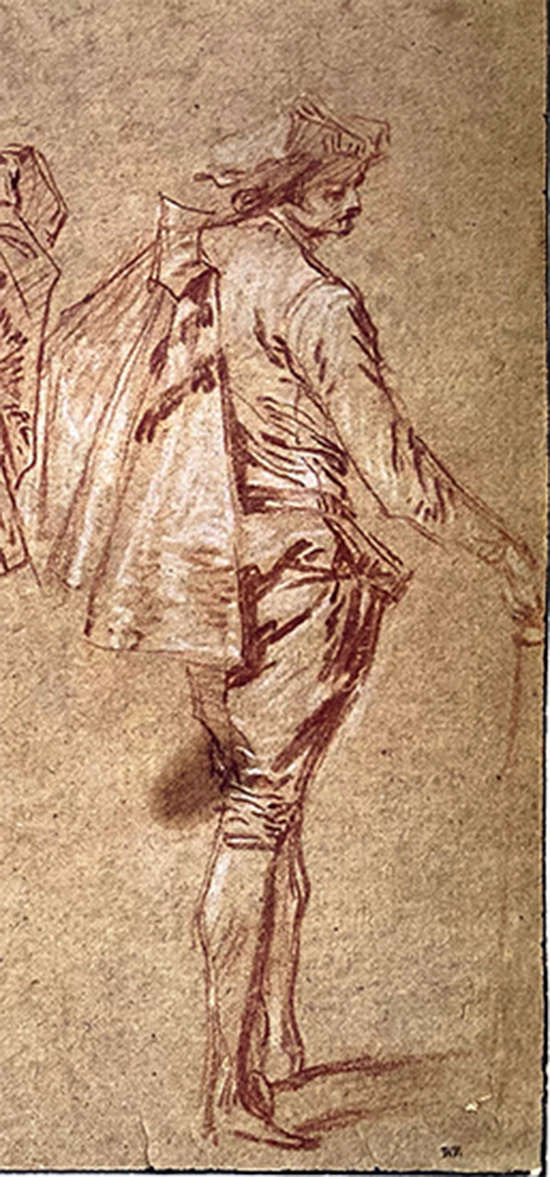

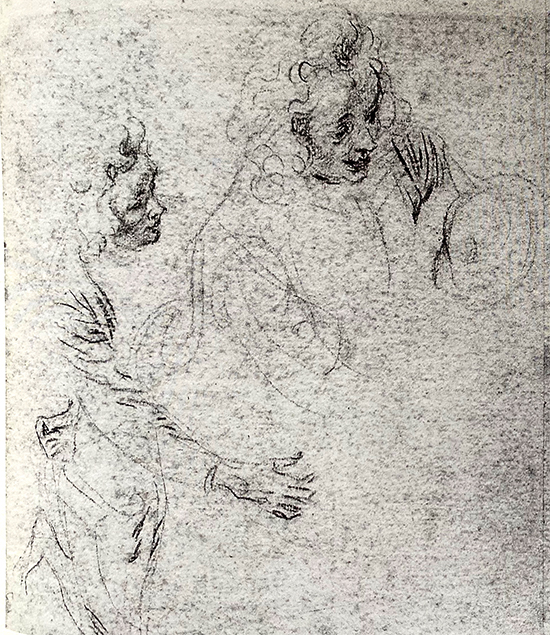

Only a few of the many drawings that Watteau originally employed for L’Assemblée dans un parc are extant. Three of the twelve figures in the foreground can be traced with certainty to extant drawings but there is evidence about the sources of his other figures.

Watteau, L’Assemblée galante dans un parc (detail).

Watteau, Three Studies of a Woman (detail), red, black, and white chalk. Los Angeles, the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Watteau, Four Studies of a Man (detail), red and white chalk. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

Jean Audran after Watteau, A Couple Strolling (detail), engraving, Figures de différents caractères, plate 205.

The strolling woman at the far left of the painting relied on a sheet of studies now in the Getty Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 466). The correspondence is exact. So too, her companion can be traced to a drawing in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 504).

Watteau brought these two, otherwise unrelated figures together on the canvas, first probably using chalk to indicate the major lines and the details of drapery folds. Then, using his brush and dark brown pigment, he painted over his primary indications to preserve them and guide him as he laid in the color. However, before adding the color, he made a counterproof, pressing paper against this area. The result is similar to Watteau’s chalk counterproofs, only the medium is oil paint rather than red chalk. Although this oil counterproof has not survived, its existence can be surmised from an engraving by Jean Audran, plate 205 of the Figures de différents caractères. Certain features in Audran’s engraving, especially the blurred quality of the man’s face and the way his chin resembles a short beard, suggest that the counterproof was not pressed correctly. While it might be argued that that Audran’s engraving records a lost Watteau drawing where he redrew his two studies from the model, this was not the artist’s practice, whereas he was accustomed to make oil counterproofs. Rosenberg and Prat would have us believe that Audran copied the two figures from the painting—an argument that they advanced for several other plates in the Figures de différents caractères with paired figures—but there is no reason to believe that Jullienne’s engravers would have betrayed Jullienne’s expressed desire of recording Watteau’s drawings.

Watteau, L’Assemblée galante dans un parc (detail).

Watteau, Study of a Seated Woman, red, black and white chalk, 23.5 x 14.2 cm. United States, private collection.

The woman at the right of the painting, repulsing a man’s overly forward advances, was based on a drawing in a private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 543).

Watteau, L’Assemblée dans un parc (detail).

Watteau, Studies of Men and a Woman’s Hand (detail), red, black, and white chalk. Whereabouts unknown.

The flutist at the far right of the painting, his lower body hidden by shrubbery, was taken from a drawing that recently reappeared on the auction market (Rosenberg and Prat 536).

Watteau, L’Assemblée dans un parc (detail).

Watteau, Three Studies of a Young Man (detail), red chalk. Geneva, private collection.

It has been claimed that the overly zealous man reaching toward the woman at the right was derived from a sheet of studies of a man with outstretched arms (Rosenberg and Prat 506). He supposedly was based on the figure at the left, but the match is troublingly inexact. The cast of his body is slightly different, and the fingers are splayed differently.

Jean Audran after Watteau, Study of a Standing Child, engraving, Figures de différents caractères, plate 21.

Jean Audran after Watteau, Study of a Reclining Child, engraving, Figures de différents caractères, plate 177.

Watteau, Assemblée dans un parc (detail).

It was noted by Parker (but not by Rosenberg and Prat) that two of the children in the painting can be traced to lost Watteau drawings, studies that were recorded in the Figures de différents caractères. The standing girl seen from behind was engraved by Jean Audran as plate 21, and the young girl reclining on the ground appears as plate 177.

Watteau, L’Assemblée dans un parc (detail).

Watteau, Fêtes venitiennes (detail), oil on canvas. Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland.

Surely, though, Watteau called upon drawings for the other figures. For example, there must have been a drawing of the woman seated on the ground at the far right, her fan in her lap, her head turned to speak to the man lying on the grass. Watteau used that same lost drawing for a figure in Fêtes venitiennes. So too, he employed the drawing of the women being groped for both L’Assemblée dans un parc and Fêtes venitiennes. Also a lost drawing used for the woman seated on the grass and seen from behind in L’Assemblée dans un parc (see Rosenberg and Prat R 733) was also used for Fêtes venitiennes. Quite possibly the two pictures were painted at about the same time.

REMARKS

Although L’Assemblée dans un parc was not included in the Oeuvre gravé, almost no critics have expressed doubt about the picture’s authenticity. Indeed, it is the quintessential Watteau fête galante. Elegantly dressed members of a leisured class sit and walk through an extensive landscape, not the formal terrain of a Le Nôtre garden but the meadow of an Elyssian field. Polite conversation, even an excess of amorous zeal, but no clear narrative. The music of a single flutist is heard, but even that is casual accompaniment—background music rather than a formal concert. The trees in the distance part to allow a vista, but it is not necessarily an indication of where one should go. in fact, a pool of water keeps us from attempting to reach that distant place.

Probably because this painting was not engraved in Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé, it did not inspire copyists to repeat the composition. Indeed, it is one of the few major Watteau fêtes galantes so singularly devoid of copies. On the other hand, because it has been in the Louvre since the mid-nineteenth century, it has enjoyed a central place in the Watteau literature. Its lack of narrative content and its dark tonality, the result of Watteau’s poor painting technique, and restoration when the painting came to the Louvre, encouraged writers to rhapsodize over what they read as Watteau’s depiction of the penumbral melancholy of love. Huyghe, for example, wrote of “les reveries automnales et somptueusement châtoyantes.”

Unlike the situation with most Watteau paintings, there is a general consensus as to when L’Assemblée galante dans un parc was executed, namely around 1717. Mathey and Posner would date it c. 1716; Brookner, Temperini, and Glorieux have opted for 1716-1717; Macchia and Montagni, as well as Roland Michel and Rosenberg and Prat prefer 1717; Adhémar dated the painting to 1717-18.