- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Les Charmes de la vie

Entered November 2017; revised December 2024

London, Wallace Collection, inv. P410.

Oil on canvas

67.3 x 92.5 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

The Attractions of Life

The Charms of Life

Concert champêtre

Garden Party in the Champs Élyseés

The Music Party

Vue des anciens Champs Elysées

RELATED PRINTS

Pierre Aveline after Watteau, Les Charmes de la vie, engraving, c. 1730.

Les Charmes de la vie was engraved in reverse by Pierre Aveline. The print was announced for sale in the August 1730 issue of Mercure de France (p. 1831).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Claude or Jean-Baptiste Glucq, 1730. Aveline’s engraving recorded the owner as “Glucq.” It is unclear which of the two art-loving Glucq brothers was intended. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold identified him as Jean-Baptiste, while Adhémar claimed it was Claude.

Sale, Paris, November 11, 1784, anonymous sale, lot 35: Vue des anciens Champs Elysées de la galerie des Tuilleries, sous laquelle se voit une société intéressante, occupée à faire de la musique: une jeune fille pince de la guitarre; elle est entourée de plusieurs figures qui l'écoutent: au milieu de cette composition est un jeune homme qui accorde un instrument, il est debout & se détache dessus le ciel par une opposition vraie; à côté un negre prépare des rafraîchissemens. Ce Tableau est un des plus beaux de ce Maître, qui a réuni l'agrément & l'ingénuité à la plus grande richesse de ton. Il est gravé par Aveline.”

Paris, collection of Pierre de Grand-Pré (painting dealer). His sale, Paris, February 16-24, 1809, lot 39: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . Peint sur toile, haut. 34, larg. 24 p. Un Tableau de la plus riche couleur, d'une touche spirituelle et d'un dessin aussi fin que correct. Il représente le Sujet agréable de divers Personnages, Hommes, Femmes et Enfans, rassemblés sous un grand Vestibule d'architecture, pour faire de la musique et prendre une collation. La Figure qui se fait distinguer davantage dans le milieu de la composition, est un Homme de la plus belle figure, dans un habillement espagnol, qui est dans le mouvement d'accorder sa Guitare. Un vaste point de vue de paysage présente encore de riches détails dans le lointain, qui se détachent avec autant d'art que de goût sur un ciel frais et brillant. Il a été gravé sous le titre du Concert champêtre.” The painting sold for 172 livres to “Chaise” according to the copy in the Rijksbureau vor Kunsthistorische Documentatie.

London, with Simon-Jacques Rochard (1788-1872; miniature painter); sold to Lord Hertford. Rochard’s ownership is affirmed in a letter he wrote to Prosper Merimée in which he claimed to be one of the earliest collectors of Watteau’s paintings, and he listed Les Charmes de la vie among the seven Watteau pictures that had been in his possession.

Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th Marquess of Hertford (1800-1870), before 1854. Rochard’s sale of Les Charmes de la vie to the Marquess of Hertford is recorded in a letter from Mawson to Hertford, written before May 2, 1856: “like your Lordship’s splendid picture bought of Rochard.” Seen in Hertford House by Waagen IV, p. 83. By descent to Sir Richard Wallace, and then to his widow, Lady Wallace. Bequeathed to the nation in 1897.

EXHIBITIONS

London, Bethnal Green, Paintings, Porcelain, Bronzes (1874), cat. 377 (as by Watteau, A Music Party, lent by Sir Richard Wallace).

London, Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters (1889), cat. 93 (as by Watteau, Garden Party in the Champs Élyseés, lent by Sir Richard Wallace).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 104.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 105.

Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854-57), 4: 83.

Goncourt , L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 117.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), no. 52.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 183.

Hendy, “Watteau and Rubens” (1926), 137-39.

Miller, “Borrowings of Watteau” (1927), 44 n. 6.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 157.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 31-32.

Puyvelde-Lasalle, Watteau et Rubens (1943), 16.

Sutton, Les Charmes de la vie (1946), 3-22.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 157.

Mirimonde, “Sujets musicaux chez Watteau” (1961), 263-66.

London, Wallace Collection, Pictures and Drawings (1968), 362-64.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 184.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A24.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 228.

Ingamells and Lank, “The Cleaning” (1983), 733-39.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 160, 223, 228-29, 266, 270, 273, 291.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 123, 157, 160, 200, 239.

Gétreau, “Watteau and Music” (1984), 542.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), under cat. 48.

Ingamells, Wallace Collection, French (1989), 361-65.

Vidal, Watteau's Painted Conversations (1992), 42-44, 111, 151.

Plax, Watteau and Cultural Politics (2000), 135-37.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 106, cat. 94.

Sund, “Middleman: Watteau and Les Charmes de la Vie” (2009), 59-82.

Vogtherr, ''Fêtes galantes in London and Potsdam” (2009-10), 180-84.

Vogtherr, Watteau at the Wallace Collection (2011), cat. 5.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 241-42.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), 13-41.

Duffy and Hedley, Wallace Collection's Pictures (2004), 471-72.

Vogtherr, Watteau at the Wallace Collection (2011), 8-90.

Brussels, Leçon de musique (2013), 32,146; cat. 109, 124.

Paris, Jacquemart-André, Watteau à Fragonard (2014), 34.

Plomp and Sonnabend, Watteau: Der Zeichner (2016), 198-200.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau, Le Concert (detail). Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg.

Watteau, Les Charmes de la vie (detail).

Bernard or Jean Audran after Watteau, Standing Theorbo Player, engraving. Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal.

Although Les Charmes de la vie is essentially a variant of Watteau’s earlier Le Concert in Berlin, they actually have few figures in common. One of the major ones that they do share is that of the theorbo player tuning his instrument. The drawing for this musician has not survived but it was recorded in reverse in an engraving by Bernard or Jean Audran. The print was ultimately not included in Jullienne’s Figures de différents caractères, but an impression of it is preserved in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Paris. Few differences appear in a comparison between the Audran engraving and the musicians in Le Concert and Les Charmes de la vie. The question is whether Watteau copied the figure from one painting to the next, or each time referred to his original drawing from the model. Given that the musicians in the two paintings appears together with the woman playing the guitar and the girl toying with her spaniel, it seems probable that the artist transferred the image from one canvas to the second without referring to his original drawing.

The child playing with a spaniel in the foreground of both paintings was based on an extant drawing, one that is now in the Musée du Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 229). The child appears in the lower center of the sheet, but minus the dog. Although there are multiple studies of the same child on the page, none of them were used for either Les Charmes de la vie or Le Concert. Thus the second child appearing in both paintings must have come from a sheet similar to the one in the Louvre.

The problems of understanding Watteau’s working methods are highlighted again here. There is the basic issue of whether he relied solely on his first version of the painting or turned back to his original drawings when creating the second version. Equally intriguing is the relationship of these works to other Watteau paintings where the same figures reappear. The theorbo player appears once more in Pour nous prouver que cette belle. The child playing with the dog appears again in Le Passe temps and Assemblée galante; here the question concerns not only the source of the child but the ensemble of the child and the dog.

Most of the remaining principal figures in Les Charmes de la vie can be traced to extant Watteau drawings. One of the most fascinating of these is the man standing at the left of the painting. He is not another anonymous model but Watteau’s close friend Nicolas Vleughels. Watteau made many drawings of his friend, but the one he used for this painting is the study now in Frankfurt (Rosenberg and Prat 338). This artist did not return to Paris until the spring of 1715, which gives us a terminus post quem for both the drawing and the painting.

The striking figure of the woman playing the guitar in Les Charmes de la vie originates in a sheet of studies in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 596) that shows her in two slightly different poses, the second time with another woman placed next to her as though singing. When Watteau took the leftmost figure over for his painting, he repeated the details quite faithfully except that he added an unexplained extra layer of fabric around her waist and changed her chair from a plain, wooden ladder-back to a gilt one with red velvet upholstery, adding an additional note of elegance to this already palatial scene.

There is a second seated woman in Les Charmes de la vie, absorbed by the words spoken to her by the man leaning over her shoulder. She was taken directly from a sheet in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 587). It seems likely that this sketch was once part of a larger sheet with other studies. Her male companion, whose head alone is visible in the painting, was based on a drawing that, fortuitously, is also now in the collection of the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 564). This drawing likewise shows only his head, but did Watteau draw it this way just for the painting? Probably not.

Also to be considered is the black servant adjusting bottles of wine in the copper bucket. His head is derived from a drawing in the Louvre containing several studies of two young black men’s heads (Rosenberg and Prat 608). Although these studies were drawn from life, the motif of a black servant taking charge of bottle of wine in a cooler curiously echoes Veronese’s banquet scenes.

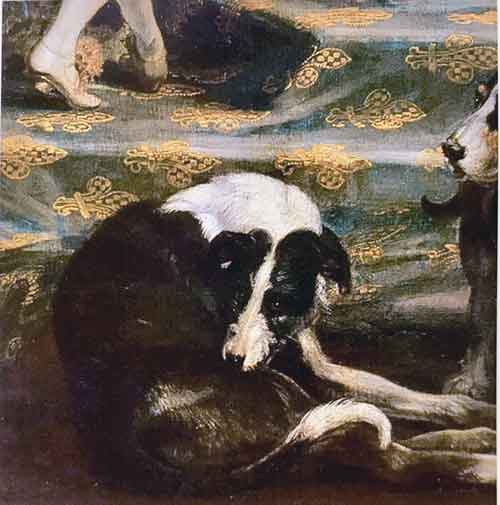

There is no known drawing for the dog curled up on the terrace, indecorously licking its hind parts. Yet surely there was one, for this animal was borrowed from one in the foreground of Rubens’ Coronation of Marie de’ Medici. In Les Charmes de la vie the dog is in the opposite sense of Rubens’ canine. In L’Enseigne de Gersaint the dog reappears exactly thesame,but in Watteau’s Le Jugement de Paris it appears in the same sense as Rubens’ dog. Watteau’s fascination with the Flemish master’s dogs is remarkable.For example, he copied the small yapping dog in the Birth of Louis XIII and inserted the pet in La Surprise. A drawing with studies after the Old Masters (Rosenberg and Prat 359) includes one of a dog licking discarded plates in a hamper that Watteau copied from Rubens’ Kermesse, a painting whose elements he studied closely. Although the drawing of the dog licking itself that he studied from the Coronation of Marie de’ Medici and employed for Les Charmes de la vie has not survived, its one-time existence can be confidently presumed.

REMARKS

X-rays taken of the Wallace Collection painting reveal the dramatic changes that were made during the course of the painting’s execution. When Watteau first established the figures in Les Charmes de la vie, he remained close to Le Concert in that he brought over the theorbo player and the two children, as well as a number of secondary figures that appear at the right side of Le Concert: a woman seated on the ground, seen from behind; her recumbent male companion; and a woman and man strolling away who turn to look back over their shoulders. They were then covered over during the course of painting, and were replaced by less fully realized figures placed farther back in the landscape. These changes assure the anteriority of Le Concert.

Other changes are visible in the x-ray of Les Charmes de la vie. Watteau reworked the group at the right. He removed the figure of a woman who was originally seated next to the guitarist, and another portion of an additional figure, replacing them with a different seated woman and a man peering over her shoulder.

From the start, it would seem, Watteau planned on placing the standing figure of Vleughels at the left, whereas a woman had stood there in Le Concert. He also chose to portray Vleughels in his Fêtes venitiennes, where Vleughels’ face was painted over a pre-existing figure and he dances to the music of a bagpipe played, it would seem, by Watteau. The two men were good friends and lived together, first under Crozat’s roof and then in a studio they shared. Scholars have largely been concerned with their artistic interchanges, especially since they occasionally copied each other’s work—be it figure studies or landscapes. The question generally ignored is whether their relationship was restricted to friendship or whether it ran deeper.

As was mentioned, Vleughel’s presence in Les Charmes de la vie establishes that it was painted after that artist returned from Italy, that is, no earlier than the spring of 1715. And almost all critics agree that it was painted after Le Concert, the fête galante now in Berlin. Posner’s is the only dissenting voice but the x-rays of Les Charmes de la vie prove him wrong. Despite the generally unanimous view that Les Charmes de la vie is the second, more mature work, there is no agreement on exactly when it was painted. Adhémar dated it to 1716, her catch-all for most of Watteau’s paintings; Roland Michel posited both c. 1718 and 1717-19; Rosenberg proposed c. 1717-18, Temperini suggested 1718, while Posner and Vogtherr dated it 1718-19. In short there is a general but not specific unanimity.

Earlier interpretations emphasized the harmony and gallantry of this gentleassembly of members of society, but recent critics have sought to impose novel, personal readings. Perhaps the most important was that of Mirimonde, who focused on the man tuning his theorbo. Because that stringed instrumentwas notedfor its tendency to fall out of tune, Mirimonde saw the inclusion of this instrument and the emphasis on the musician tuning it as both an emblem of discord and an ironic comment on the difficulties of love. Critics have been intrigued by this idea. Posner, who consistently imposed complex amorous narratives on Watteau’s paintings, wrote that the man peering over the guitarist’s shoulder is the lutenist’s rival and he is successfully pressing his suit, while “the lutenist’s inadequacy as a musician spells his failure as a lover.” This was repeated by subsequent critics, including Rosenberg. But Mirimonde’s interpretation and the subsequent fanciful manipulations of his thesis read the cup as half empty rather than half full. If maintaining relationships is difficult, then in this scene of intimacy the musician tuning his instrument could perhaps be read as emphasizing the harmony that with effort can be achieved in music and society.

Plax’s reading of the theorbo player is wholly novelistic. She contrasts the ideal state of love expressed by the musical instruments with the physical desires of men. In her view, the men’s hands are swollen and signify “displaced erotic desire.” Plax declares that the hands of some of Watteau’s musicians, including those of the theorbo player, “seem to stumble, as if the men’s desire has made it impossible for them to pursue the sort of controlled amorous ritual implied by the playing of the stringed instrument, a symbol for elevated, ideal love.” Her association of hands and aroused phalluses is surely extreme. But Sund has pushed this line of interpretation still further. Not unexpectedly, she characterizes the theorbo as “none-too-subtly phallic” and adds that “the clumsiness of his endeavor to subjugate it” speaks to his ineptitude as an instrumentalist and lover. (Furthermore, she views the black servant grasping the neck of a wine bottle as a gesture of masturbation.) Would Watteau recognize his painting in these texts?

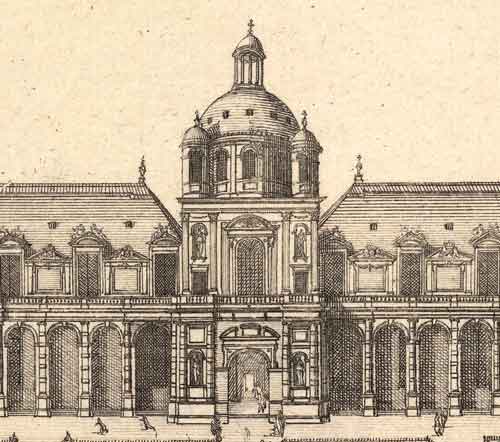

One of the striking features of this painting is its architectural setting. What was its source? Similarly banded columns are featured in Watteau’s Les Plaisirs du bal and, less emphatically, in Sous un habit de Mezetin. They also appear in many of Rubens’ paintings, such as The Garden of Love and some of the scenes in the Marie de’ Medici series, paintings that Watteau was drawn to. Beyond this pictorial tradition, there were two buildings in Paris built in this style, both for Marie de’ Medici: the Luxembourg Palace—at least its garden façade—and the Tuileries Palace, the palace between the Louvre and the Tuileries Garden. In fact, when Les Charmes de la vie was sold in 1784, it was described specifically as “Vue des anciens Champs Elysées de la galerie des Tuileries.” The details of the Tuileries’ facades are known to us through engravings and photographs made before it burned to the ground in 1871. However, while banded columns were certainly a feature of the building, especially on the central pavilion, there were no large openings or halls along the ground floor, and the columns were not alternately light and dark.

Nonetheless, the identification of the setting of the painting as the Tuileries Palace is an attractive myth and has frequently been intoned. When the painting was exhibited in 1889, for example, it was entitled Garden Party in the Champs Élyseés. That idea has been repeated by modern critics, including Adhémar and Temperini. Watson, while accepting the basic concept, rightly noted that there were differences between the painting and the actual building. Vogtherr is alone in insisting that the building represented here is the Luxembourg Palace. He believed that the proof was to be found in the fact that the dog in the painting was taken from Rubens’ Coronation of Marie de’ Medici, a painting which was in that palace. But such reasoning defies logic. In truth, the architecture depicted in Les Charmes de la vie corresponds less to either real building than it does to the fantasy structure in Les Plaisirs du bal.

Apropos of the provenance of the painting, Adhémar suggested that it came from the collection of King Louis-Philippe d’Orléans (1773-1850) and that it was sold in London at Christie’s on May 28-30, 1853, lot 31: “WATTEAU. . . . A landscape, with figures representing actors of the Comedie Italienne—a composition of eight figures . . .” However that picture proves to be a Lancret painting now in the Wallace Collection, Italian Comedians by a Fountain, inv. P465. Similarly, Denys Sutton introduced the notion that Les Charmes de la vie had been sold from the collection of Paul Periet on December 18, 1846. However, as Watson observed, this provenance belongs to another Lancret painting in the Wallace Collection, Mademoiselle Camargo, inv. P393.

For copies of Les Charmes de la vie CLICK HERE