- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

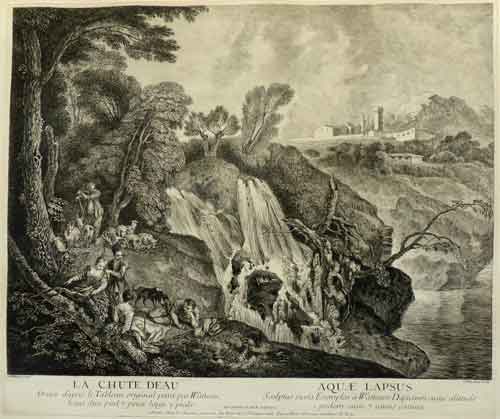

La Chute d’eau

Entered June 2018; revised January 2020

Valenciennes, Musée des beaux-arts, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lionel Sauvage to the American Friends of the Louvre, depôt du musée du Louvre

Oil on canvas

52 x 64 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

La cascata

RELATED PRINTS

The painting was engraved by Jean Moyreau in 1729 and was announced for sale in the March 1729 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 542).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). The picture was in Jullienne’s collection in March 1729 when the engraving was announced for sale in the Mercure de France, June 1729, p. 542. The caption on the engraving states “du Cabinet de Mr Jullienne.” The painting was sold from the Jullienne collection by 1756 when the manuscript inventory of his holdings was prepared (now in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York).

Madrid, collection of Francisco Alfonso Pimentel y Borja, 11th Duke of Benavente (1706-1763). By descent to his daughter, María Josefa Alonso-Pimentel, 12th Duchess of Benavente and Duchess of Osuna, (1752-1834), who married Pedro Téllez-Giron, 9th Duke of Osuna (1755-1807).

El Alameda d’Osuna, a castle nine kilometers from Madrid. Desparmet Fitz-Gerald (p. 6) claims to have seen La Chute d’eau there in 1885, at which time it was one of a group of three paintings, each labeled “Escuela flamenca” on their frames. A printed paper label on the reverse of the painting declares “de la antigua casa ducal de Osuna” and this corresponds to the phrase used in the 1895 catalogue of the Osuna collection.

Given by Duchesse d’Osuna to her confessor, whom Desparmet Fitz-Gerald (p. 6) seems to suggest was Don Rodriguez of Valladolid. By descent to his nephew, José Rodriguez of San Sebastian (Desparmet Fitz-Gerald, pp. 5-6). He supposedly advertised the painting for sale in 1907; however, it was probably not bought by Desparmet Fitz-Gerald until the late 1920s. He was an active dealer trading in paintings of the Spanish school, often buying them in Spain and bringing them back to Paris.

Paris, with Xavier Desparmet Fitz-Gerald (1861-1941; artist and art dealer) by 1928-29. The painting’s presence in Paris was acknowledged first by Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold. Desparmet Fitz-Gerald published a book about the painting around this time.

Paris, anonymous sale, Galerie Charpentier (Ader), June 24, 1937, lot 49: “WATTEAU

(JEAN-ANTOINE) . . . La chute d'eau. Par une belle journée d'été, deux couples sont venus chercher l'ombre et la fraîcheur sur la rive d'un torrent dont les eaux se brisent, au centre, contre des rochers, et retombent en cascade au creux d'un gouffre.

Derrière eux, un berger, appuyé sur sa houlette, garde ses chèvres et ses brebis. A gauche, les édifices d'une ville.

Toile. / Haut., 0m52; long., 0m64. / Cadre en bois sculpté. / Gravé par Moyreau.

Ancienne collection de M. Jean de JULLIENNE, à Paris. / Ancienne collection du duc de BENAVENTE Y PIMENTEL, à Madrid. / Ancienne collection de Mme la duchesse de BENAVENTE, à Madrid. / Ancienne collection de l'ALAMEDA D'OSUNA, près Madrid. / Collection de Don RODRIGUEZ, à Valladolid. / Collection de Don José RODRIGUEZ, à Saint-Sébastien.

RÉFÉRENCES BIBLIOGRAPHIQUES : Mars 1729. — Gravure de « La Chute d'Eau »; annoncée au Mercure de France, p. 542. Novembre 1845 à février 1846. — L'Artiste, p. 78. Hédouin. Essai de Catalogue de tableaux de A. Watteau, n° 110. « La Chute d'Eau », gravé par J. Moyreau, cabinet de M. de Jullienne. 1875. — De Goncourt. Catalogue raisonné de l'œuvre peint et gravé d'Antoine Watteau, n° 192. « La Chute d'Eau », du Cabinet de Jullienne. 1922. — Émile Dacier et Albert Vuaflart. Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIIIe siècle, t. III, p. 81 ; n° 164. « La Chute d'Eau ». « La peinture originale mesure d'après l'estampe I p. 7 po. x 2 p., c'est-à-dire 0,513 x 0,648. D'après l'estampe du Cabinet de M. de Jullienne : « Ne se trouvait plus dans la coll. de Jullienne en 1756, « époque vers laquelle a été dressé un cat. manuscrit, illustré de dessins, des peintures « appartenant à cet amateur. » 1929. — Jacques Herold et Albert Vuaflart. Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIIIe siècle. Notices et documents biographiques, t. I, p. 263, n° 164. « La Chute d'Eau ». « Le tableau de « La Chute d'Eau », en sens inverse de la gravure, actuellement coll. de M. Desparmet Fitz-Gérald à Paris. » Op. cit. Tome IV. Planches, n° 164. « La Chute d'Eau », gravé d'après le tableau original peint par Watteau. Haut. 1 pied 7 pouces (sic), large 2 pieds. Cabinet de M. de Jullienne. Bibliothèque Nationale, Cabinet des Estampes. Cf. Œuvre de A. Watteau. Il est regrettable que les épreuves du temps aient enlevé à ce tableau l'éclat qu'il devait avoir à l'origine.

Appartenant à MM. T. et D. F... et vendu en vertu de jugements. / Voir la reproduction, pl. X.”Paris, private collection. In 1950 Adhémar indicated that it was in Paris, and this is confirmed by the 1951 exhibition at the Galerie Charpentier, a modest show with loans from local sources. However, “private collection” may have been a euphemism for its being with a dealer.

Oslo, collection of Ludvig G. Braathen (1891-1976; maritime and airline entrepreneur). By descent to his son Bjorn G. Braathen, and then to his grandson.

London, Christie’s, July 7, 2009, lot 49: “Jean-Antoine Watteau . . . La Chute d’eau / oil on canvas laid onto panel / 20 1/8 x 24 7/8 in. (51.1 x 63.2 cm.) / £100,00-150,000 / US $160,000-230,000 / €120,000-170,000. . . The painting will appear in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Watteau's paintings by Alan Wintermute, currently in preparation.” Bought for £121,250 ($196,304) by Lionel Sauvage.

Paris and London, collection of Ariane and Lionel Sauvage. In 2015 the work was donated to the American Friends of the Louvre, depôt du musée du Louvre.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Plaisir de France, 1951.

Valenciennes, Musée de beaux-arts, Reveries italiennes, 2015.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 110.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 111.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 58.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 192.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 263; 3: cat. 164

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 201.

Desparmet Fitz-Gerald, La Chute d’eau (c.1929).

Barker, Watteau (1939), 107.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 88.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 34, 67.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 273-76.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 86.

Ferré, Watteau, 1972, 1: 208, 212, “1729”; 4: 1107, 1120.

Roland Michel,Watteau (1981), cat. 125.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 159-60, 265-66.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 109.

Luna, “Watteau et l’Espagne” (1987), 231.

Eidelberg, “Watteau’s Italian Reveries” (1995), 121-22.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 122, R359.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 21.

Glorieux, “Watteau et le Nord” (2004), 52.

Michel, «Le célèbre Watteau» (2007), 211 n. 51.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 208-09.

Eidelberg, Rêveries italiennes (2015), 12-29.

RELATED DRAWINGS

The one Watteau drawing that can be directly linked to La Chute d’eau is a an early sheet of studies of men, mostly sitting or reclining, now in the Stockholm Nationalmuseum (Rosenberg and Prat 122). At the very top of the page is a figure of a recumbent man who rests his head on a bent arm, and he corresponds to the figure at the left of the foreground group in the painting. Because this sheet is a weak counterproof, only his other arm, crossing his body, and the direction of his head are easily understood. More of this figure would have been visible in the original chalk study. The sheet now in Stockholm is one of a group bought from the artist in 1715 by Swedish count Charles Gustav de Tessin. This means that the original drawing was made no later than 1715—a date that may help determine when the painting was executed.

A landscape drawing of a thundering waterfall in Montpellier is also directly linked to La Chute d’eau. It shows exactly the same landscape seen in the painting—with trees and tangled roots in the foreground ledge, the rocks and trees in the midst of the surging water, and a distant town in the left background. The scene represents the famous falls at Tivoli, outside of Rome, a site frequently depicted by visiting Netherlandish and French artists from the sixteenth century onward, including Paul Brill and François Stella. And there is a corresponding engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. When this essentially unknown drawing was published in the 1960s, Eidelberg recognized that Watteau must have based his painting on this sheet but he wrongly proposed that it was a copy after a lost Watteau drawing. The incisive style of the Montpellier drawing is more emphatic than we might expect from Watteau’s hand, and since he had never traveled to Italy, he could not have recorded the site first-hand. Jean-François Méjanès’ proposal, written on the mount of the Montpellier drawing, that the drawing was by a member of the Sylvestre family, many of whose members had gone to Italy, was more reasonable. In Paris, Watteau must have had access to this study and used it as the basis of his painted landscape. Certain of the changes he introduced when using the drawing might be expected: his reduction in importance of the trees in the middle distance, and, especially, his enlargement of the foreground shelf to accommodate the figures he added there.

REMARKS

Portions of the painting’s early provenance are murky. First is the issue of its passage to Spain. Other Watteau paintings were taken from Paris to Madrid in the early eighteenth century, such as the Contrat de marriage and L’Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune. So too, the Leçon de chant and Amoureux timide made the same journey south. To whom they were sold and who transported them remains unknown. The early history of La Chute d’eau is similarly ambiguous.

In fact, we cannot be certain that the painting went directly to Spain. A London sale on May 5, 1748, contains a tantalizing reference to a picture listed under the name of Watteau and described as showing “A Landscape with a Water fall.” The sale was led by Robert Bragge and many of the pictures came from the collection of the prime minister of England, Sir Robert Walpole, owner of several Watteau paintings. There are very few paintings in the Watteau oeuvre which fit this description other than this work, a small panel in the Louvre, a similar painting that was in the Natoire collection, and the landscape in the Hermitage–-none of whose whereabouts can be traced securely in the first half of the eighteenth century. Thus it is possible that Walpole owned La Chute d’eau before it traveled to Spain.

Desparmet Fitz-Gerald’s unsubstantiated claim that in the eighteenth century the painting was in the collection of the duke of Benavente (he does not name the specific duke) may have been a hypothesis to explain where the painting was in Spain before it entered the Osuna collection.

A catalogue of the Osuna collection was prepared by Narciso Sentenach in 1895 and published the following year. The phrase used to describe the collection, “de la antigua casa ducal de Osuna,” is the very same phrase printed on a long paper sticker that remains affixed to the back of the present painting. But, if Desparmet Fitz-Gérald’s account is correct, La Chute d’eau had been given away by 1895, which explains why it is not listed in the printed catalogue. Precipitated by the Osunas’ declining fortune, the family’s art collection was auctioned in May 1896, the very same year that the catalogue was printed, with the book serving as the auction catalogue. An additional page inserted in the front of the book, “Exposición y Venta de los cuadros e demas objetos de arte de la antigua casa ducal de Osuna,” bears the date of March 1896. An earlier auction of the Osuna collection of arms and armor, as well as furniture and some works of art, had been held in Cologne, at J.M. Heberle, on November 24-December 2, 1890.

The painting’s misattribution to the Flemish school when it was in the Osuna collection helps explain how it managed to stay unobserved. As we know from the 1896 catalogue, there were two other landscape paintings in the Osuna collection of approximately the same size. They were both Flemish and showed scenes set in the countryside—one with women and soldiers picnicking, and the other with women and men but without a citation of their activity: “197—Reunión de damas y guerreros merendando en el campo. Lienzo.—Alto, 0,51; ancho, 0,63. 198—Reunión de damas y caballeros en el campo. (Compañero del anterior.) Lienzo.—Alto, 0,51; ancho, 0,63.” Certainly La Chute d’eau would have fitted comfortably with these two subjects, although a trio of such paintings would be unusual. Usually such groupings are arranged in evenly numbered sets, with two, four, or eight works. On the other hand, Luna’s theory that there was a set of four pendants and that they all were by Watteau seems highly unlikely.

Before the actual painting came to light around 1930, the engraving was acknowledged but it elicited little comment. Since its rediscovery, the painting has been accepted by all scholars. It has suffered losses in the landscape, but not in the foreground figures. The greatest loss was in the white highlights that evoke the roaring cataract, and in some of the trees in the center of the composition, although the clearing and restoration in 2009 helped clarify the surface immeasurably.

Whereas there rarely is agreement regarding the dating of most Watteau paintings, the great majority of scholars seem agreed that La Chute d’eau was created in 1712. This was the opinion expressed by Adhémar in 1950, and then by Mathey, Macchia and Montagni, Temperini, Glorieux, and the Christie’s cataloguer. Roland Michel opted for a slightly later dating, c. 1713-14. Indeed, one cannot equate the charming peasant figures in the foreground with the stiffly posed, cardboard creatures in Les Jaloux, the painting that Watteau submitted to the Académie in 1712 when he was agréé. If Les Jaloux characterizes Watteau’s art in 1712, then it seems probable that La Chute d’eau represents a slightly later stage, closer to 1714-15, a period when Watteau was exploring Italian landscapes. The Christie’s cataloguer claimed that the “the comparatively flat planes of the landscape, [are] so reminiscent of painted stage backdrops,” such as the Bal champêtre in the Noailles collection. Yet the landscape of La Chute d’eau is deep and inviting, and, moreover, the Noailles painting is generally not considered to be from 1712 but rather from several years later.

Until recently it had not been realized that La Chute d’eau depicted the great falls at Tivoli. In fact, except for Posner and Eidelberg, no scholar had even commented on this most unusual landscape, although it clearly did not represent the Île de France. As Posner noted, “It brings Italian hill towns to mind, and the architecture at the upper left does, in fact, seem rather Italianate. The craggy rocks and precipices, and the turmoil of rushing water especially recalls views of the waterfalls at Tivoli painted by Poussin’s brother-in-law, Gaspard Dughet . . . and some works by him may very well have inspired Watteau.” However, as Eidelberg pointed out, Watteau had not been dependent on any drawing or painting by Dughet. Instead, he had relied on the drawing in the Montpellier museum, now attributed to a member of the Sylvestre family. It had been drawn on site and Watteau had adopted all of its essential features—the foreground shelf of space (which he deepened to provide space for his figures), the cataract falling in two main streams, and the distant town.

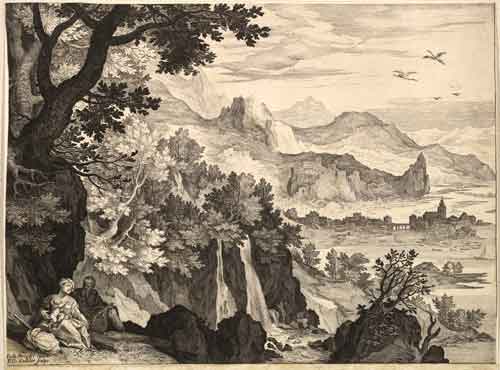

Aegidius Sadeler, after Jan Bruegel the Elder, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, c. 1596, engraving.

This notwithstanding, in 2004 and again in 2011 Glorieux needlessly claimed that Watteau had relied on a print by Aegidius Sadeler after a painting by Jan Bruegel the Elder for the topography of the waterfall (Bruegel had actually visited Italy firsthand). While it is true that the Flemish print depicts the waterfalls at Tivoli, Sadeler’s rendering is far less specific than the Montpellier drawing in recording the rocks, the trees, and the distant town.

Moreover, as demonstrated in 1995 and again in 2015, La Chute d’eau is one of a larger group of Watteau paintings dependent on drawings that portray specific sites in Rome and its environs. La Promenade sur les remparts, one of the earliest in the series, features the Campo Vaccino and was painted perhaps a few years earlier than La Chute d’eau. So too, Watteau’s La Ruine, which depicts the interior of the Colosseum, should also be classified earlier. La Mariée de village, with Vignola’s Sant’ Andrea in via Flaminia dominating the background, is close in spirit and execution to La Chute d’eau.