- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

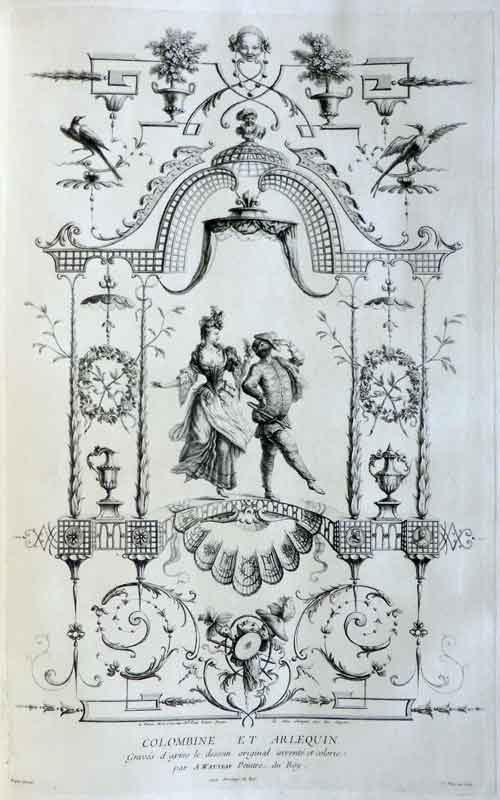

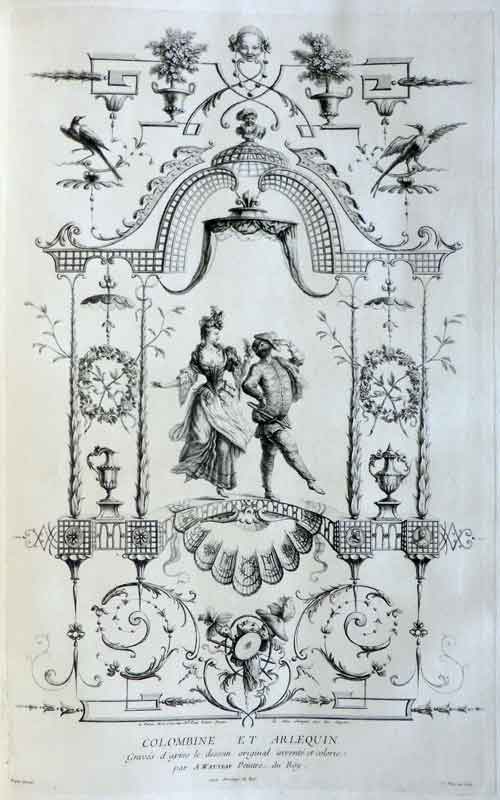

Colombine et Arlequin

Entered June 2018; revised January 2020

Presumed lost

Watercolor or gouache on paper

Measurements unknown

RELATED PRINTS

This composition was engraved by Jean Moyreau, and the print was announced for sale in the April 1729 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 751).

PROVENANCE

No trace of this composition has been found in eighteenth- or nineteenth-century sales.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 2: 59.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 306.

Fourcaud, “Watteau: Peintre d’arabesques” (1908-09), 130.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 3: cat. 64.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), 3: cat. G 146.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Although there are a number of extant preparatory studies by Watteau for arabesques, they are never fully rendered, symmetrical compositions of the type recorded in Moyreau’s engraving. Generally just the right side of the arabesque is drawn, and the left side is a variant design or is left blank. A noticeable exception is a fan design in the British Museum, La Coquette, whose significance is discussed below.

It seems likely that Watteau would have turned to separate figure studies of Harlequin and Colombine for this composition. While his specific models are not known, one of the counterproofs that Swedish count Charles Gustav de Tessin bought from the artist in 1715 suggests the type of drawings he might have used: a study of a masked Harlequin holding a guitar aloft, his leg raised or resting on a step (Rosenberg and Prat 17). His jaunty, active posture is like that of the two theatrical characters in Colombine et Arlequin, and is found in other early Watteau drawings and paintings.

REMARKS

Almost no attention has been paid to this arabesque, yet the neglect should not be attributed simply to the absence of Watteau’s original design. Many of Watteau’s other arabesques are also known only through the Jullienne engravings yet they have engaged scholars’ attention. Whatever the reason, this early design invites more serious study.

The central figures in this arabesque are quite elongated, with disproportionately small heads and tall, scrawny bodies. Their proportions and awkward suggestions of movement find parallels with the central figures in Watteau’s Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, an early picture. The same traits characterize a couple at the center of La Coquette, the early fan design in the British Museum, London.

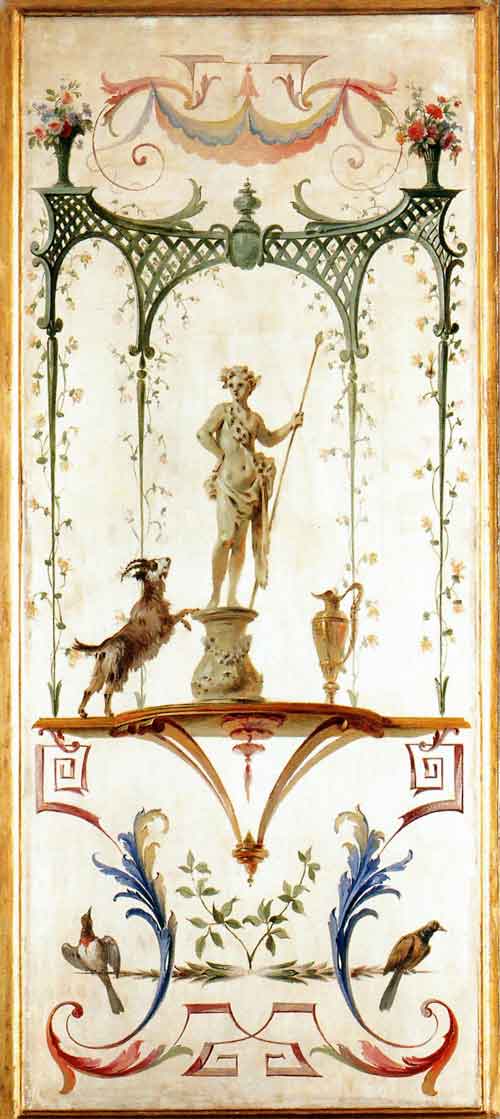

Colombine et Arlequin has been related to Watteau’s stay with Gillot, but Gillot’s arabesques rarely included theatrical characters. By contrast, Colombine et Arlequin is wholly consistent with other early arabesques Watteau executed while working with Claude III Audran. It can be favorably compared with L’Enjoleur and Le Faune, two arabesques originally in the Hôtel de Nointel, Paris. The three share several elements: foliate scrolls, trellises, leafy colonettes, urns, containers with bouquets and shrubs, even the birds on branches. The couple in L’Enjoleur, it should be noted, has the same proportions and awkward movements seen in Colombine et Arlequin.

All these stylistic analogies suggest that Colombine et Arlequin was executed early in Watteau’s career. While a date of c. 1710-13 can be posited, the absence of firm chronological markers leaves the question slightly unresolved.

Watteau, A View of a Distant Town, 16.2 x 22 cm, red chalk and watercolor. Haarlem, Teylers Museum.

A major issue surrounding Colombine et Arlequin is its medium. The unusual legend beneath the engraved image declares: “Gravés d’après le dessein original inventé et colorié par A. Watteau . . . .” Whereas “inventé” and “dessiné” are standard terms, “colorié” is quite unexpected. What does it imply? The arabesque may have had washes of watercolor, as seen in the striking landscape in the Teylers Museum, Haarlem (Rosenberg and Prat 135).

Watteau, La Coquette, 21.5 x 42.3 cm, gouache, black chalk, heightened with white, on Japanese paper. London, British Museum.

It is equally likely—perhaps more so—that Watteau employed gouache on Colombine et Arlequin. This was the medium he used for the beautiful fan design, now in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 189). It is a drawing (black chalk is visible underneath) that is colored with gouache; thus it could be described as "dessiné et colorié" much like Colombine et Arlequin. When La Coquette was engraved for the Jullienne corpus it was designated “A. Watteau pinxit;” however Rosenberg and Prat have classified it among Watteau’s drawings. This registers the ambiguity surrounding this mixture of mediums. We have chosen to list Colombine et Arlequin and La Coquette among Watteau's paintings, and have also classified his other gouaches under this rubric, such as his study of roses recorded in the Charles Coypel sale of 1753.