- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Les Comédiens italiens

Entered June 2019; revised August 2022

Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1946.7.9

Oil on canvas

63.8 x 76.2 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

A Company of Italian Comedians

The Italian Comedians

Pierrot: a Group

RELATED PRINTS

Watteau’s painting was engraved in London by the French-born Bernard Baron, who had taken up residence in the British capital. The engraving, in reverse of the painting, was included in Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé and was announced for sale in the March 1733 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 554).

PROVENANCE

London, collection of Dr. Richard Mead (1673-1754; royal surgeon). His ownership of the painting is indicated on Baron’s engraving: “Tiré du Cabinet du Dr Mead.“ London, Langford, Mead sale, March 20-22, 1754 (3rd day): “A Company of ITALIAN COMEDIANS, by the same [Watteau], and of the same size (Two feet by two feet six inches). Watteau being in England, and not in the best health or circumstances, Dr. Mead relieved him in both, and employed him in painting these two pictures, which are engraved by Baron.” Sold to Wood for £52.10 according to an annotated copy of the catalogue. Mead’s ownership and sale of Les Comédien italienes and the pendant L’Amour paisible is attested to in George Vertue’s Note Books: “ Dr. Meade for whom he painted two pictures, that were sold in the doctor’s collection.”

London, with Thomas Wood (1708-1799; art dealer?).

London, collection of Francis Beckford (d. 1768).

London, collection of Roger Harenc (1693-1763). His sale, London, Langford, March 1-3, 1764 (3rd day), lot 52: “WATTEAU . . . A musical Conversation, and Italian Comedians, its Companion.” Sold for £8.18 to the duke of Grafton, according to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Dokumentatie.

London and Euston Hall, collection of Augustus Henry, 3rd duke of Grafton (1735-1811).

London; with Asher Wertheimer (1843-1918; art dealer).

London, with Thomas Agnew and Sons, Ltd., London; purchased and sold in 1888 to the 1st earl of Iveagh.

Elveden Hall, Suffolk, and Iveagh, County Down, collection of Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st earl of Iveagh (1847-1927); by descent to his third son, Walter Edward Guinness, 1st baron Moyne (1880-1944).

Paris, New York, and London, with Wildenstein & Co., purchased February 18, 1930, from Baron Moyne.

Schloss Rohoncz, Rechnitz, Hungary, and Amsterdam, collection of Baron Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza (1875-1947) by July 1930; sold to Wildenstein & Co. before December 1936.

New York, with Wildenstein & Co., by December 1936; sold November 23, 1942 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

New York, Samuel H. Kress Collection; given in 1946 to the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

EXHIBITIONS

London, Royal Academy, Old Masters (1871), cat. 176 (as Watteau, Pierrot: a group, lent by Thomas Baring).

London, Corporation of London, Works by French and English Painters of the Eighteenth Century (1902), cat. 40 (Antoine Watteau, Comédiens italiens [Italian Comedians], lent by Lord Iveagh).

Munich, Neue Pinakothek, Sammlung Schloss Rohoncz (1930), cat. 348 (Watteau, Die italienischen Komödianten).

Munich, Alte Pinakothek, on extended loan (1930-31).

London, Royal Academy of Arts, Exhibition of French Art 1200-1900 (1932), cat. 260 (177) (Watteau, Comédiens italiens, lent by Schloss Rohoncz, Hungary).

Washington, National Gallery, Recent Additions to the Kress Collection (1946), no. 774.

Washington, National Gallery, Picasso: The Saltimbanques (1980), cat. 1.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 71.

Athens, National Gallery, From El Greco to Cézanne (1992), cat. 26.

Ishikawa, A Gift to America (1994), cat. 36.

Ottawa, National Gallery, The Great Parade (2004), cat. 1.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854-57), 4: 96-97.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 74.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 75.

Goncourt, L’Art du XVIIIe siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 68.

Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England (1876), 2: 295.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 119.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 70.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 68, 147.

Graves, A Century of Loan Exhibitions (1913-15), 4: 1625.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 96, 99; 3: cat. 204.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 70.

Vertue, "Note Books" (1933-34), 23.

Cairns and Walker, Masterpieces of Painting (1944), 110.

Frankfurter, “French Masterpieces” (1944), 10, 24.

Washington, National Gallery, Kress Collection (1945), 158.

Washington, National Gallery, Recent Additions (1946), cat. 774.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 211.

Panofsky, “Gilles or Pierrot?” (1952), 334-39.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 69.

Mirimonde, “Sujets musicaux chez Watteau” (1961), 273, 283.

Nicoll, The World of Harlequin (1963), 92-93.

Cairns and Walker, Masterpieces of Painting (1964), 110.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 31-34.

Brookner, Watteau (1967), 17-18, 23, 40.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 203.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B21.

Eisler, Kress Collection (1977), 300-06.

Pope-Hennessy, “Completing the Account” (1977), 10.

Raines, “Watteaus and ‘Watteaus’ in England'” (1977), 57, 62.

Chan, “Watteau’s ‘Les Comédiens italiens’" (1978-79), 107-112.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 244.

Bryson, Word and Image (1981), 77-79.

Posner, “Another Look at Watteau’s Gilles” (1983), 97-99.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 107, 177.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 120, 263, 265-67, 269, 291.

Grasselli, Drawings of Watteau (1987), 2: 390-95, 542-45.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 179, 219, 479, 481, 507, 519, 621, 622, 624, 647, 649, 651.

Heck, Picturing Performance (1999), 2-5.

Börsch-Supan, Watteau (2000), 53-54, 62.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 127, cat. 110.

Bryant, Kenwood (2003), 15-16, 416.

Hanson, “Mead and Watteau’s ‘Comédiens italiens’” (2003), 265-72.

New York, Wildenstein, Arts of France (2005), 78.

Glorieux, “L’Angleterre et Watteau” (2006), 50-51, 59, 71-72.

Conisbee, French Paintings (2009), cat. 99.

Grasselli, Renaissance to Revolution (2009), under cat. 42.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 344, 319-27.

Sund, “Why So Sad?” (2016), 322-23, 325.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), under cat. 24, 54, 86.

Paris, Jacquemart-André, Watteau à Fragonard (2014), under cat. 27

Washington, National Gallery of Art. http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/art-object-page.32687.html

RELATED DRAWINGS

Remarkably, there are not only individual studies from the model for many of the fifteen characters in this composition but also several important compositional studies.

The young actor at the upper left portion of the painting, his cape stretched out, is based on a red chalk drawing in Minneapolis (Rosenberg and Prat 623). Watteau employed this same study for his equally late Gilles in the Louvre, and possibly also for Les Deux cousines. The young actress whose face attracts the actor's fond gaze is based on a vigorously rendered drawing now in a private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 519).

Watteau, Les Comédiens italiens (detail).

Watteau, Study of a Guitarist, red chalk, 15.8 x 10.3 cm. Alençon, Musée des beaux-arts de la dentelle.

The guitarist seated on the steps is taken from a red chalk drawing in the Alençon museum (Rosenberg and Prat 219). It is rendered in such quick, broad terms that one wonders if Watteau prepared a more detailed study of the actor’s costume and head.

The two children in the lower left of the Comédiens italiens were delicately studied on a sheet in Rotterdam (Rosenberg and Prat 649). In the painting the larger child looks more directly at us, whereas in the drawing his head is tilted downward and to the side. But he may not have needed an additional study. In the drawing the child at the right looks directly out but in the painting looks slightly downward and to the side. This may have been an adjustment made while the painting was being created, without the need of an additional study.

The actress to the left of Pierrot was based on a drawing in the British Museum, showing not only her face but also the head of a charming small dog (Rosenberg and Prat 647). Did Watteau rely on another study for defining her body and dress?

The young actor at the right side of the painting derives from a study now in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 507 verso). This study was apparently made expressly for this painting. Watteau's original study for Dr. Baloardo, a delicate but expressive drawing, is now in California (Rosenberg and Prat 624). The artist must have used a counterproof of this sheet for the painting, where the doctor appears in reverse.

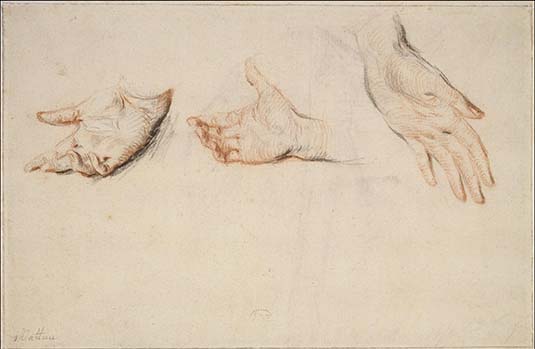

Watteau, Three Studies of a Hand, red and black chalk, graphite, 15.2 x 23 cm. London, British Museum.

One of the most fascinating drawings associated with Les Comédiens italiens is a sheet in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 507). On the side considered the recto are three studies of a hand. The middle study served for the hand of Brighella, gesturing to Pierrot. The hand at the left was probably used for Harlequin. What makes it fascinating is that the verso of the sheet in London contains the study for the young actor pulling back the curtain, a drawing discussed above. It is rare to find two sides of one sheet used for the same painting.

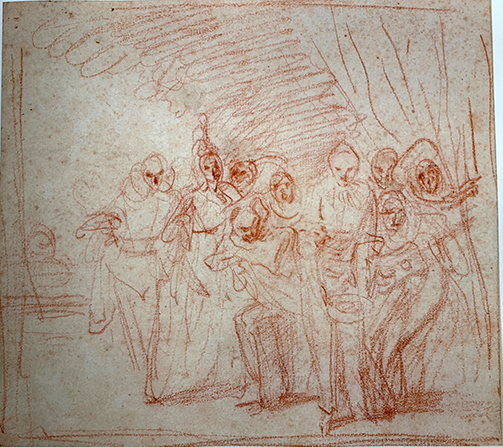

Watteau, Compositional Study with commedia dell’arte characters, red chalk, 17.5 x 21.7 cm. Paris, École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts.

Four compositional studies by Watteau are related to Les Comédiens italiens, which is quite extraordinary. As far as can be determined, Watteau never spent so much effort in working out a composition on paper.

Probably the first in this series of compositional studies is a sheet in the École des beaux-arts, Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 179 verso). Curiously, it was not included or rejected in Rosenberg and Prat’s recent study of Watteau’s drawings. It is a very lightly drawn red chalk sketch, but the characters are surprisingly easily to distinguish. The group of comedians is off-center to the right, divided into essentially two groups: the one at the left has a static figure flanked by two players looking in at him; the second group is a standing guitarist and a Crispin with his typical costume. With hindsight we can presume that the static figure is Pierrot and while here he is flanked at either side by the two women, in Les Comédiens italiens, they appear together at one side. The strumming guitarist in the painting has been moved to the other side and is seated. The Crispin at the right is a motif that Watteau had employed earlier in Pierrot, Arlequin, Scapin. He returned to the idea in another study for Les Comédiens italiens but then eliminated him in the final painting. Above, at the top right are diagonal lines representing what will be the theater curtain of the painting.

Watteau, Compositional Study with commedia dell’arte characters, red chalk, 16.9 x 18.4 cm. London, British Museum.

The second of the drawings, in the British Museum, is more firmly drawn and the figures are more resolved (Rosenberg and Prat 552). Once again the group of comedians is off to the right side. Pierrot, bowing and with his hat in both his hands, is posed as in an early drawing and in Comédiens sur le champ de foire. He is surrounded by his colleagues in a way that approaches the Washington composition. At least one of the actresses stands behind him, and the guitarist crouches at the other side. An actor just behind Pierrot seems to pull back, countering the actor at the far right who points out of the picture. This tension around the calm Pierrot foreshadows the scheme in the Washington painting. Finally, a curtain at the right is pulled back and establishes that the scene is being played on a stage.

The third of the compositional studies (Rosenberg and Prat 622) shows at the center a bowing Pierrot, his hat in his hands as in the previous drawing. He now is at the center of the ensemble as in the final painting. Surrounding him are equally balanced groups of comedians; in a general way this drawing anticipates Les Comédiens italiens more so than the previous two studies. At the left a Mezzetin strumming his guitar and a grappling couple anticipate similar figures in the Kress painting, and at the right are a twisting Harlequin and an actress leaning forward to view Pierrot better. All these elements presage what Watteau established in his final painting, though in a different order. The stage setting portrays an urban milieu of classically inspired buildings—a type of painted backdrop used in French theaters—although that is unlike the setting in the Kress painting. The curtain pulled up at the right prepares the way for the one in the painting.

Watteau, Compositional Study for Les Comédiens italiens, red chalk, 14.5 x 17.9 cm. Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André.

The fourth and final compositional study for the Washington painting is in the Musée Jacquemart-André (Rosenberg and Prat 621). Apart from the sculpted nude in the left corner (the same statue appears in the foreground of Réunion en plein air, Dresden), the remainder of the design closely corresponds to Les Comédiens italiens. The foreground stairs, the Pierrot, and the figure of Sylvia or Flaminia embracing Pierrot’s shoulders are all as Watteau would paint them in the Washington picture. However, the figure of Crispin bounding in from the right side was not retained in the painting.

REMARKS

One of three paintings that Watteau is known to have executed when he visited London in 1719-20, Les Comédiens italiens has all the qualities of his late works, especially the monumental character of the figures and their emotional warmth.

The second painting that Watteau executed in London was L’Amour paisible. In the eighteenth century it was paired with Les Comédiens italiens, and both were owned by Dr. Richard Mead. The contemporary remarks in George Vertue’s Note Books, the descriptions in the Mead sale catalogue, and the captions on Baron’s prints reinforce the idea of Mead’s patronage. Adhémar needlessly proposed that Mead could have bought L’Amour paisible prior to the artist’s arrival in London. Equally curious, Eisler questioned whether Mead purchased Les Comédiens italiens directly from the artist. All other critics have rightly accepted that Watteau painted these works when he was in London, between very late 1719 and August 1720, by which time he had returned to Paris.

In regard to the early provenance of Les Comédiens italiens, Robin Simon has kindly clarified the identity of “Wood,” the buyer of the painting at Dr. Mead’s sale. He was Thomas Wood of Littleton Park, Staines, Middlesex. On a previous occasion, in 1745 at the Hogarth sale, he bought that painter’s Actresses Dressing in a Barn, and the following day sold it to Beckford (see Elizabeth Einberg, William Hogarth, A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings (New Haven and London: 2016), cat. 103. Evidently the two men had an understanding between them.

Les Comédiens italiens and L’Amour paisible seem unlikely pendants. Although the figures in both works are of the same scale, the latter composition is set lower on the canvas, creating a disequilibrium. Yet the two works share certain qualities and seem to correspond. In both works, children are tucked into the lower left corner, both have a central focus, and one of the male protagonists at the center makes a sweeping gesture with his arm. Whether or not the pairing of these two compositions is to our taste, they were paired when they were in Dr. Mead’s collection and when they were subsequently owned by Beckford and Harenc.

Les Comédiens italiens features fifteen actors grouped closely, in an arrangement that some have likened to a final curtain call. They stand before a semicircular stone apse, with a central opening crowned by a sculpted mask. On the central axis stands Pierrot (or Gilles) in his traditional white costume. To our right, in a brillant yellow costume adorned with black brandenburg fastenings, stands Brighella; with a broad gesture he brings our attention back to Pierrot. Standing at the clown’s side and holding onto his shoulder is a young actress, possibly playing Flaminia or Sylvia, two relatively undifferentiated roles. At the right, the aged Dr. Baloardo, shown resting on his cane in a customary pose, his line of sight blocked by Brighella, leans forward to get a glimpse of Pierrot. At the left, seemingly indifferent to the central character, is Mezzetin strumming his guitar, Harlequin in his traditional, contorted pose, and a pair of young lovers, possibly Mario and Isabelle as suggested by Connisbee, although there are no fixed costumes to identify these secondary actors. At the lower left is the Fool—not a character in the commedia dell’arte—and two children. This is an ensemble uniting as though accepting applause now that they have played their piece. As the flowers strewn at Pierrot’s feet establish, it was a success. Indeed, there is a slight, subtle smile on Pierrot’s face

Watteau, Les Comédiens italiens.

Watteau, Sous un habit de Mezzetin, 28 x 21 cm. London, Wallace Collection.

Watteau, Arlequin, Pierrot, Scapin, 18.6 x 23.8 cm. Waddesdon Manor, Rothschild Collection.

As in so many of Watteau’s later paintings, there are reminiscences of earlier works—especially the idea of a theatrical troupe posed together, looking out to the viewer. Sous un habit de Mezzetin, reputedly a portrait of Sirois and his family rather than a portrayal of an actual troupe of commedia dell’arte characters, has the same basic formula. In that painting, it is Mezzetin who takes center stage and the arched opening is off to the side rather than in the middle. But the basic premise remains of a central character flanked by actors and a child. Likewise, Watteau’s Arlequin, Pierrot, Scapin anticipates other aspects of Les Comédiens italiens. Here a stiffly posed Pierrot, his arms immobile at his sides as in the Kress painting, looks out to the audience. Here too he is surrounded by his fellow actors, including a young man in the upper right who pulls back the curtain, just as in the Kress painting. As Watteau’s several compositional studies for Les Comédiens italiens reveal, endless possibilities existed: different characters could be included or excluded, and the players could be placed at left or right of the central actor.

Watteau’s painting is so compelling that it has invited various interpretations. When Baron’s print was first made available in Paris, it was described in the Mercure de France as “Presque tous portraits de gens habiles dans leur art que Watteau peignit sous les différens habits des acteurs du Théâtre Italien.” The task of identifying the specific actors is a frustrating exercise, especially since we cannot be certain whether Watteau was trying to portray the actors of the troupe in Paris or the one in London. Or was he portraying friends and models who were dressed in commedia dell’arte costumes? Some scholars have been quite categorical in naming the actors. For example, when the painting was shown in Munich in 1930, the names of the actors and the roles they were playing were named as though documented beyond doubt. An alternative and curious explanation circulated at the start of the twentieth century and was repeated by Staley, namely that Watteau had portrayed all the leading male and female sculptors of the day.

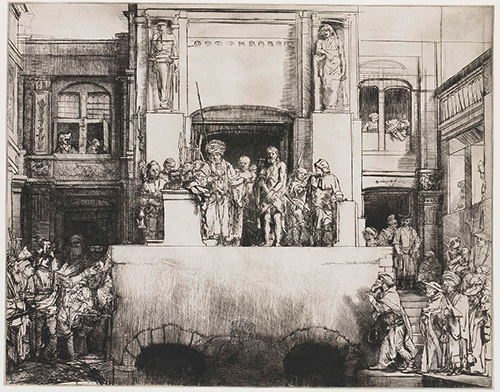

Rembrandt, Christ Healing the Sick (the Hundred Guilder print), c. 1647-49, etching.

Rembrandt, Ecce Homo (Christ Presented to the People), 1665, etching.

Most contemporary scholars’ discussions of this painting are colored by Dora Panofsky’s interpretation of the work. Although she first distinguished the development and differentiation of the characters Pierrot and Gilles, she then turned to the Washington painting, which she saw as the artist’s final testament. Writing with the skills of a modern art historian using references to past artistic traditions, she posited that Watteau identified with the suffering Christ, with the Christ of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder print and Christ Presented to the People. Posner rightly dismissed her interpretation as based on “a fortuitous visual relationship.” Indeed, several of Panofsky’s basic premises need to be reconsidered.

A first, very basic issue is whether Watteau's paintings were as melancholic and tragic as she would have us believe. It is useful to remember Dezallier d’Argenville's testimony that although Watteau had bouts of melancholia, his paintings showed none of this: “Watteau, whom work made melancholic, never painted it in his pictures: one finds gaiety and a live and penetrating spirit throughout.“ Likewise, Gersaint denied any melancholic element in Watteau’s paintings, noting that his subjects were pleasant, despite the artist’s nature. Yet nineteenth-century critics exploited the idea that Watteau and his art were not only melancholic but tinged with tragedy. Thus Jules Michelet (La Regence), a true nineteenth-century Romantic, wrote of the Gilles in the Louvre: “He attains tragic heights often, once even the sublime also. The example: the Italian clown . . . the great Gilles. At his last triumph, overwhelmed by success, shouting and flowers, he returns before the public, humble and with lowered head. . . . He dreams; he is as if swallowed up. Morituri te salutant. Hail people, I am to die.” Like Michelet, whose text she probably read, especially since it had been reprinted in Adhémar’s Watteau catalogue just a year earlier, Panofsky turned the Pierrot of Les Comédiens italiens into a self-portrait of the artist, and then into a suffering Christ-like figure, about to die. But the Pierrot of the Washington painting is not a suffering Christ. In fact, there is a slight smile upon his lips.

Also, we should consider the degree to which Watteau was interested in the art of Rembrandt. Whereas he was drawn to Rubens’ corpulent energy, Rembrandt did not exert the same attraction. Watteau may have occasionally emulated Rembrandt, as in his borrowing one of the Dutch master’s composition for his L’Indiscret, and he probably remembered Rembrandt’s Danae when he posed his model for Femme nue et couchée. But there is no evidence that Watteau was drawn to the pathos and human emotion expressed so nobly in the art of Rembrandt. Watteau’s preparatory studies for his paintings reveal that he was planning not a solemn Ecce Homo but, rather, a joyous, ebullient gathering.

One of the most difficult questions is what Dr. Mead knew of this theater and how he would have seen this painting. As Craig Hanson has pointed out, this man of science was well aware of the traditions of the commedia dell’arte. A pamphlet war was being waged in London at this time between Dr. Mead and a rival, Dr. John Woodard, over the proper treatment for smallpox. Commedia dell’arte characters assumed the roles of protagonists in these pamphlets. While a fascinating aperçu, Hanson’s attempt to draw more specific ties with the characters in Watteau’s painting lacks sufficient basis.

Watteau’s composition was subjected to another, even more improbable interpretation by Victor Chan. He would have us believe that the painting is meant to convey the cycle of the Ages of Man: from the children and youthful couple at the left, to the more mature figures at center, and then to the old doctor at the right. It is a clever idea but Watteau was not an allegorical or moralizing artist. Moreover, the iconography of the stages of life requires a continuous path from start to finish, whereas Watteau’s painting is centrally focused, without due emphasis on the aged doctor. Moreover, the youth behind the doctor, at the extreme right of the composition, interrupts any such chronological schema.

Separate from these hypothetical speculations, the French commedia dell’arte had particular relevance to London during the time Watteau lived there. In Paris, several years earlier, the regent Philippe d’Orléans called back the exiled Italian comedians. In 1716 they played at the Palais Royal and then at the Hôtel de Bourgogne. A rival group that had emerged in Paris in the interim, the Opéra Comique, was extremely popular (this was the theater Watteau knew), but in the face of opposition from the newly returned Italian players, it was forced to disband in 1719. Many of its players traveled to London to start a new troupe. In short, these comedians were a constant presence in Watteau's life. Whether his painting represents the last performance of the Italian players in Paris or the debut of the newly reformed troupe in London (both interpretations have their proponents) or just a recurrent theme that Watteau turned to throughout his career, the success of his painting cannot be denied. Along with the great Gilles in the Louvre and the disputed Pierrot, Mezzetin, Scaramouche, Scapin et Arlequin in the Getty Museum, these portrayals of the commedia dell’arte are the great jewels of his maturity.

The history of the Kress painting’s whereabouts in the eighteenth and twentieth centuries is remarkably well established, but there is a surprising gap in the nineteenth century. It is sometimes claimed (e.g., by Macchia and Montagni) that it was in the collection of Thomas Baring, 2nd Bart. (1799-1873) but that is incorrect. The Baring sale in London, Christie’s, June 2-3, 1848, contained three Watteau paintings: Voulez-vous triompher des belles?, its pendant, and L’Accord parfait. Dr. Mead's two paintings not only disappeared from sight during the greater part of the nineteenth century, but the pendants were separated and L'Amour paisible never reappeared.

Although the painting in the National Gallery has almost total acceptance, still, there are some naysayers. Those who have rejected the Kress painting, or preferred instead a version formerly in the Groult collection and now, coincidentally, in the National Gallery (our copy 1), include Mantz, Dilke, Phillips, Réau, Eisler, Pope-Hennessy, Posner, Ferré, and Börsch-Supan. Eisler’s idea that the Groult painting is the original and that the Kress version is a copy, executed with Philippe Mercier’s assistance, is implausible. The outstanding quality of the Kress painting speaks for itself.

Click here for copies of Les Comédiens italiens