- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire

Entered June 2019; revised June 2020

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten

inv. GK I 5602

Oil on canvas

64.7 x 91.3 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Attori della commedia dell’arte sul campo della fiera

Bauernhochzeit

Eine Dorf-hochzeit, mit einem Jahrmarkt und einer Masquerade

Une Noce villageoise avec une foire et une masquerade

PROVENANCE

Berlin, collection of Frederick II [Frederick the Great] (1712-1786; king of Prussia). Possibly recorded in Berlin by 1763; restored in 1765 (“noces de paysans de Watteau qui est crevassée, pour boucher des crevasses . . . 60 Thalers”). By 1773 the painting was in the Great Concert Hall of the Neues Palais in Potsdam. Through the nineteenth century and until 1941 it hung in the Small Gallery of Sans-Souci.

EXHIBITIONS

Potsdam, Charlottenburg, Meisterwerke aus den Schlossern Friederichs des Grossen (1962), cat. 90 (Watteau, Bauernhochzeit).

Paris, Louvre, La Peinture française du XVIIIe siècle à la cour de Frédéric II (1963), cat. 31 (Watteau, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 10 (Watteau, Actors at a Fair / Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, lent by the Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Oesterreich, Description (1773), 83.

Nicolai, Beschreibung (1786), 1146.

Rumpf, Königlichen Schlösser in Berlin (1794), 159.

Rumpf, Berlin und Potsdam (1803), 2: 63.

Dussieux, Artistes français à l’étranger (1876), 222.

Förster, “Das Gegenstuck zu Watteaus ‘Brautzug’ in Schloss Sans-Souci” (1924), 27-29.

Ingersoll-Smouse, Pater (1928), 11.

Hubner, Schloss Sanssouci (1938), 22.

Junecke, “Meisterwerke aus den Schlössern Friederichs des Grossen” (1962), 68.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965)

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 62 bis.

Eidelberg, “Quillard, Assistant to Watteau” (1970), 70 n. 53.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 1: 77-78; 3: cat. A2.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1977), v.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 95.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 115, 209, 213. 269.

Eidelberg, “Watteau’s Italian Reveries” (1995), 123-24.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 32, 98, 114, 125, 163.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 34, cat. 15.

Valenciennes, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), under cat. 22, 24.

Rosenberg, Gesamtverzeichnis französische Gemälde (2005), cat. 1240.

Toffolo, Le feste galanti (2005), 28-29.

Lauterbach, Watteau (2008), 37-39.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 67, 71.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. 1.

Eidelberg, Rêveries italiennes (2015), 46-49.

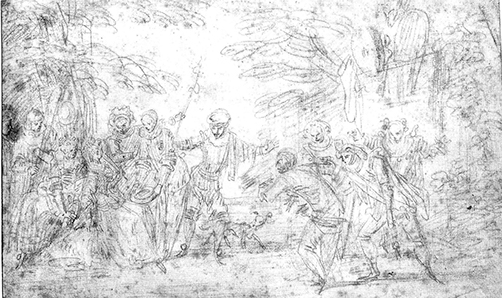

RELATED DRAWINGS

Of the fifty-some figures in this busy composition, a good number can be traced to extant drawings. Nonetheless, a great many in the painting cannot be traced to Watteau’s studies from the model. This is predictable since we have lost a disproportionate quantity of his early drawings.

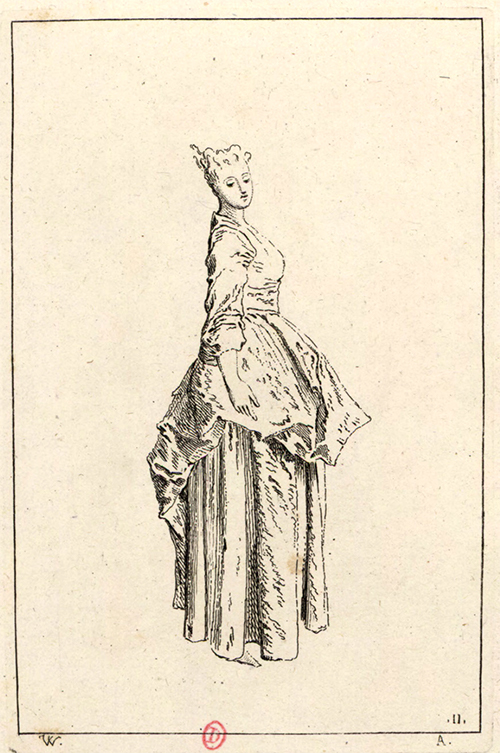

The simplest relations between Watteau's preliminary drawings and the painted figures are those instances where both elements survive, but these pairs are surprisingly few. The strolling couple in the lower right of the painting is derived from two separate studies. Unnoticed until now, the man was taken from an early sheet in the Teyler Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 102). His female companion depended on a lost study recorded in the Figures de différents caractères, plate 11.

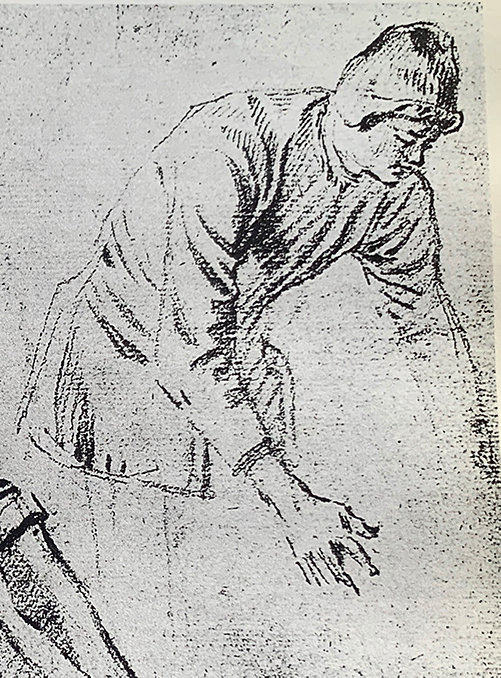

Two drawings are related to the group in the lower left of the composition, the very area that some critics have wrongly proposed was a later addition. The standing man bending forward can be traced to an early study whose present whereabouts are unknown (Rosenberg and Prat 98).

The man in the foreground, reclining on the ground, with his right arm extended in a mannered way behind him, was based on a drawing in Munich (Rosenberg and Prat 269). Watteau turned to this drawing when he was painting Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire and Le Plaisir pastoral, in both works placing him in the very foreground. Watteau also inserted this figure at the edges of groups in the middleground of other paintings, such as the Réunion en plein air in Dresden and Les Champs Elysées in the Wallace Collection. There is a problem in reconciling the assured style of this drawing with the early, more awkward style evidenced in Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire and Les Agrémens de l’esté. Rosenberg, for example, dates the Munich drawing to 1714 yet the Berlin painting to 1711. Clearly, the drawing cannot postdate the painting. Was there an earlier version of the figure study?

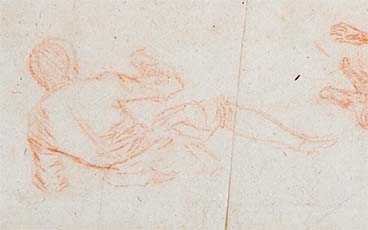

Farther back in the painting, near its center, is another man reclining on the ground; he too has his back toward us; and his right arm is extended outward, as though he were speaking. He was perhaps taken from a quick sketch whose counterproof is in Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat 122). There, however, his outstretched arm is bent at the elbow.

The dancing woman at the center of the painting, striking an awkward pose with both her left hand and leg raised, was based on a no longer extant drawing. However, that lost drawing is recorded on a Quillard sheet of studies. The adjacent woman on Quillard’s sheet, standing with her back to us, would resemble the other women in Watteau’s quadrille if her arms were raised. Quillard’s page is particularly fascinating because he copied, most, if not all, of the remaining figures from early Watteau drawings. These suggests something of the sketchbooks that Watteau kept.

One of the most intriguing relationships between Watteau’s drawings and Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire revolves around a compositional drawing formerly in the Villeboeuf collection (Rosenberg and Prat 125). Like the painting, the drawing shows a Pierrot bowing to the central woman, his hat extended outward to her. In the drawing, Pierrot—his hat still in his hand—is surrounded by a large number of other comedians, including an excited, gesturing Mezzetin and another actor who patiently stands and gestures for her to join in. Moreover, a second, more animated group of comedians at the right adds to this vivacious circle. By contrast, the painting retains only the courting Pierrot, a Mezzetin, and a comedian behind Pierrot who signals encouragingly with his staff. The question is whether the drawing was used for the painting or, equally likely, whether the drawing was done at a later moment, expanding upon the painting’s narrative. The latter is quite possible and, in fact, Philippe Mercier developed the same motif into an independent painting, as discussed below.

REMARKS

The history of Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire is curious: although it was in the German royal collection from at least the late eighteenth century and was recognized as a Watteau in the published guides, it nonetheless remained completely unknown to Watteau scholars until 1924. The one exception is a mention in Dussieux’s 1876 publication on French art outside the mother country, but this reference may be nothing more than Dussieux culling one of the Berlin guide books. How did the painting escape Zimmerman’s attention, we wonder.

It was not until Förster’s 1924 article that the painting entered the literature on Watteau. Subsequently Ingersoll-Smouse rejected an attribution to Pater and accepted the idea that it was by Watteau. Yet still the picture did not gain a firm foothold among scholars. It was wholly ignored by French critics, and was not cited by Réau or Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold. Despite the passage of fifty years, Adhémar also ignored Förster’s publication as well as the painting itself. So too did Mathey, despite his interest in Watteau’s early works. Only over the last half century has Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire finally gained a firm position in the Watteau literature.

The poor condition of the painting has been a major obstacle to its acceptance. Early on the pigment darkened and the surface crazed—problems frequently encountered in Watteau’s juvenilia. The 1765 invoice for repairs indicates that deterioration began quickly. Subsequent stages of overpainting and restoration have not helped the matter. Too many faces, for example, are “reinforced” by black contours.

In 1924 when Förster published the painting, he countered critics who were claiming that it was actually by Pater. Ingersoll-Smouse concurred with Förster, denying that it was comparable to Pater’s work, and accepted that it was by Watteau. Occasionally other negative voices have been heard. In 1965 Eidelberg rejected the attribution, misled by the poor condition of the painting, but a few years later, in 1970 and again in 1977, he recanted and upheld the attribution to Watteau. On the other hand, Posner rejected the painting, calling it an imitation of Watteau.

All scholars are agreed that Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire is one of the artist’s early works, although there is the inevitable vacillation as to exactly when the picture was painted. Lauterbach suggested c. 1708; Temperini, Toffolo, and Glorieux proposed 1708-10; Junecke, Roland-Michel, and Macchia and Montagni, proposed 1710 and also 1710-11; Saint Paulien (and Ferré) suggested c. 1711-12, as did Borsch-Supan. Rosenberg thought it earlier than 1711 and then in 1996 questioned whether it might not be c. 1711. Certainly Les Comédiens sur le champs de foire has all the characteristics we would expect in an early work—to whatever year it is assigned. The scrawny figures and their relationship to early Watteau drawings, and their association with Quillard and, as will be seen, with Philippe Mercier, all point in this direction.

Förster proposed that the work was created as a pendant to La Mariée de village. Indeed, the two paintings may have been hung as such. Their measurements are comparable and so too are their super-populated compositions. However, there are issues raised by this idea of pendants. While some critics have maintained that Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire was painted to correspond to La Mariée de village, it would have been La Mariée de village that was painted to complement Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire. Of the two works, Les Comédiens is stylistically and therefore chronologically earlier.

Anonymous Flemish artist after David Vinckboons, Flemish Kermesse, c. 1610-20. Bruges, Groeningenmuseum.

Certainly the Flemish type of subject matter in Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire and its mode of portrayal point to the early part of Watteau’s career, when he depends on Northern pictorial traditions. As in Flemish portrayals of village life and fairs, such as the many copies after David Vinckboons’ Flemish Kermesse, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire enjoys a bird’s-eye view. This provides an expansive platform on which a myriad of activities are played out—peasants dancing, merchants selling their wares, drinkers outside a tavern. Paintings such as one now in the Groeningen Museum are typical of the sorts of works that circulated freely on the French art market and that Watteau knew and freely adapted.

Anonymous French artist, La Foire de Bezons (detail), woodcut, c. 1700.

Watteau may also have been influenced by popular French prints, such as an anonymous, early eighteenth-century woodcut purportedly portraying the fair at Bezons, an annual event that took place outside of Paris. Here too there is a high point of view that allows an expansive view of the fair’s many attractions. Like Les Comédiens sur le champs de foire, various people stroll and dance in clusters here and there. Looking to the middle ground at the left we see seven fashionably dressed participants in a circle dance. Beyond them are characters from the commedia dell’arte performing. This print of the Bezons fair is interesting both as a reminder of what these public events included and the existing artistic tradition for representing them.

It is frequently written that originally the painting measured 61 x 81.5 cm, but then was enlarged, probably in the eighteenth century: an 11 cm strip was supposedly added at the left and a 4 cm strip at the bottom edge. This would have made the painting fit as a pendant to La Mariée de village, which measures 65 x 92.2 cm. If true, this would mean that the group of five figures at the lower left was not painted by Watteau. But that is not credible, especially since there is no visible break in the quality of the execution. Moreover, as we can see in Quillard’s drawings and in the copies of the composition, these groups were integral to the composition from the start. Rather than additions, these areas of canvas were part of the original composition, I think, and then at some point were folded back to reduce the size of Watteau’s canvas.

A fascinating and overlooked aspect of Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire is its relationship with the work of Watteau’s satellite, Philippe Mercier. Two of Mercier’s paintings have direct ties to this Watteau composition. Mercier’s Le Danceur aux castagnettes offers specific evidence of his knowledge of Watteau’s Comédiens sur le champ de foire. Although the dancer and the cornet player are obviously borrowed from Watteau’s Le Bal champêtre, three of the figures in the left foreground—the standing man, the seated woman leaning into her companion’s lap, and her companion—closely echo the characters in the left foreground of Comédiens sur le champ de foire. Since the latter work was not engraved, Mercier must have seen the painting first hand.

Another of Mercier’s fêtes galantes, Comedians Paying Homage to a Seated Woman, is wholly dependent on the same Watteau compositional drawing that, as we have seen, is closely linked to the group of players at the left of Les Comédiens sur le champs de foire. This association and other evidence suggest that in the mid-1710s, when Mercier was about thirty years old, he either had access to Watteau’s shop or was actually working with the master. Taken together with Quillard’s knowledge of at least one drawing for the same Watteau painting, this suggests that at least in this portion of his career, the young Watteau was at the center of a circle of other young artists. He certainly was not an isolated figure cut off from his contemporaries.

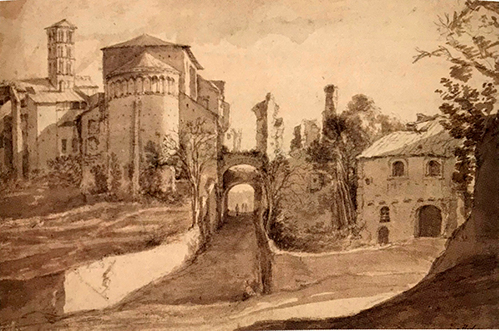

Finally, a word should be said about the landscape setting of Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, especially the portion at the right side, where the ground rises. On the top of the hill is a large building with several wings, and the portion nearest the viewer terminates in an apse with an arcade beneath the roof. It is a discrete feature, largely because of the poor condition of the painting’s surface and also because it is obscured by the foreground trees.

Jan Asselyn, View of SS Giovanni e Paolo, graphite and wash, 25 x 37.7 cm. Vienna, Albertina.

Nonetheless, this edifice is identifiable. It is not a French church but, rather, an Italian one: SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Rome. Many of the artists who visited Rome in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries stopped to draw its features, and Watteau, who never had the good fortune to visit Italy, was undoubtedly dependent on such a pictorial source. An evocation of Italy is also found in La Mariée de village, the supposed pendant to Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire. In this instance it is the church of Sant’Andrea in via Flaminia. The Italian allusion in Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire is subtle, if not timid, but it became more pronounced in later works and announces the general interest in portraying Italian sites that pervaded French landscape painting from Boucher to Fragonard and Hubert Robert.

Click here for copies of Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire