- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Conteur

Entered September 2018; revised May 2021

Whereabouts unknown

Oil on panel

34.3 x 27.3 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Artists from the Commedia dell’Arte in a Landscape

Les Comédiens ambulants

The Romancer

RELATED PRINTS

Charles Nicolas Cochin after Watteau, Le Conteur, 1727, engraving.

Watteau’s Le Conteur was engraved by Charles Nicolas Cochin and the print was announced for sale in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2677).

Edmond de Goncourt reported that Le Conteur was also engraved by Mercier, presumably Philippe Mercier. But no such print has been noted by subsequent Watteau or Mercier scholars.

PROVENANCE

Paris, Saurin, Lengeac, Veltran, and Lebrun collections, February 16, 1798, lot 49: “ANTOINE WATTEAU. . . . L’intérieure d’un parc, où l’on voit une jeune fille vêtue de blanc, surprise à jouer de la guitare par un mezzetin, un pierrot, & trois autres personnages. – Haut. 12 p. ½, larg. 10 p. B.” Sold to Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun.

Paris, with Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun (1748-1813; artist and dealer). His sale, Paris, September 29, 1806, lot 129: “ANTOINE WATTEAU. . . . La Joueuse de Guitare surprise dans un jardin, composition de six figures; Tableau digne du Titien pour la couleur. Il se trouve gravé dans l'oeuvre de ce maître par C. N. Cochin.” Sold for 80 francs to Pierre-Joseph Renoult.

Paris, anonymous sale, December 16, 1839, lot 108: “WATTEAU (Antoine).—Un joli tableau plein de grâces et de naïveté offrant, au milieu d’un parc, une jeune fille assise jouant de la guitare; elle est surprise par un amant, qui se jette à ses genoux. Plusieurs autres personnages arrivent sur la scène. Ce charmant tableau est de la touche la plus spirituelle et la plus délicate.” Sold for 266 francs.

Paris, collection of François Marcille (1790-1856; seed merchant). His sale, Paris, January 12, 1857, lot 149: “WATTEAU (attribué à). . . . Jeune femme pinçant de la guitare.” Sold for 172 francs to Fleury.

Paris, sale, Hôtel Drouot, November 24, 1863, Riquet collection, lot 78: “WATTEAU (A.) . . . Le Conteur. Toile. Gravé.” Sold to Riquet.

Paris, sale, Hôtel Drouot, March 5, 1866, Riquet collection, lot 46: WATTEAU (A.) . . . Le Conteur. Vente Marcille.” Sold for 95 francs according to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue.

Paris, collection of Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905).

Paris, collection of Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949). Seized by the Nazis in 1940-41, but returned after the war. Rothschild inventory no. ER 57, (the inventory no. R63, and possibly the label “1485/(R) 15,” both on the reverse, relate to the Nazi requisition of 1940-41).

Tel Aviv, collection of Baroness Batsheva de Rothschild (1914-1999). Her sale and others, London, Christie’s, December 13, 2000, lot 61: “ANTOINE WATTEAU . . . Le Conteur. Artists from the Commedia dell’Arte in a landscape / oil on panel / 13 ½ x 10 ¾ in. (34.3 x 27.3 cm.) / Estimate £1,500,000-2,000,000 US$2,2000,000-2,900,000 / €2,600,000-3,500,000 / PROVENANCE . . . EXHIBITED . . . / Literature . . . / Engraved . . . / . . . The re-emergence of Le Conteur has permitted technical analyses to be performed on the painting for the first time. Infra-red reflectography shows the understructure of the paint surface, and has revealed Watteau's changes of mind as the composition evolved, the most important of which was his decision to eliminate a fully finished figure of a woman who was originally seated on the ground beneath the group of background figures: her upraised hand, shoulder, and face are easily recognized in the radiographs, and she was evidently turning her head to observe the central couple. No chalk study has yet been identified for the figure, but Watteau would undoubtedly have made one. The artist replaced this figure with dark foliage in the final painting (thus it appears in Cochin's engraving as well), although it is not evident why he chose to eliminate her. He habitually worked out the compositions of his paintings on the canvas or panel itself, often making extensive alterations in the process.

Although Mme. Adhémar (op. cit.) believed that there had existed another, earlier version of Le Conteur which was last seen at auction in 1866, there is no compelling reason to think it was not the present picture; certainly, technical examinations have now demonstrated conclusively that the Rothschild panel is Watteau's first version of the subject (Camesasca mentions a reference in the archives of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to a supposedly authentic version of the composition in a private collection in the United States; nevertheless, no trace of such a picture can be found). The composition was copied frequently, however, and Adhémar (ibid.) and Ferré (op. cit.) record several sales in which various copies or versions appeared; a poor copy that is often cited in the literature is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Chartres. One copy, published in Oude Kunst (November, 1919), and now in the Musée Van Gelder, Antwerp, was attributed to Philippe Mercier, while a charming replica on canvas by Jean-Baptiste Pater (Ingersoll-Smouse, op. cit., no. 597) was sold recently at Sotheby's, New York, 14 January 1988, lot 195; there is every reason to think that Pater would have based his version on the direct study of Watteau's original. Jacques de Lajoue is not known to have reproduced the picture in its entirety, but he regularly adapted motifs from it into his own compositions: one of the most successful of these is The Swing (sold, Christie's New York, 2 November 2000, lot 236) which includes Mezzetin and the man behind him from Watteau's picture, but in reverse and undoubtedly copied from Cochin's print (see Wintermute, op. cit., p. 40, fig. 37). This lot will be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Watteau's paintings now being prepared by Alan Wintermute.”

Bought by Knight & Hall Ltd. For £2,423,750.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Galerie Martinet (1862), . . . (by Watteau, Les Comédiens ambulants).

Paris, Orangerie, Chefs-d'oeuvres des collections françaises retrouvés (1946), cat. 2 (by Watteau, Le Conteur).

London and New York, Knight and Hall, Untitled exhibition (2001), cat. 15 (by Antoine Watteau, The Romancer).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 191.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 120.

Dacier, Hérold, and Vuaflart, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 254; 3: cat 4.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 65.

Ingersoll-Smouse, Pater, (1928), under cat. 597.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau, (1931), 11, 44, under no. 40.

Barker, Watteau (1939), 137.

Florisoone, “Exposition de chefs-d'oeuvre retrouvés” (1946), no. 15.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 168.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), p. 68.

Mirimonde, “Sujets musicaux chez Watteau” (1961).

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 36-37.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 132.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B31.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 177.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984) under cat. D75a.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 223, 272, 298-99, 302.

Grasselli, Drawings of Watteau (1987), 352-54, cat. 247-49.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996) cat. 400, 501, 553, R118.

Roland Michel, “Rosenberg Prat Catalogue” (1998), 54.

Grasselli, Review of Rosenberg and Prat (2001), 324.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Although there are six figures and a dog in Le Conteur, only a few preliminary drawings can be associated with this painting. Yet several of them provide fascinating insights into Watteau’s studio practice.

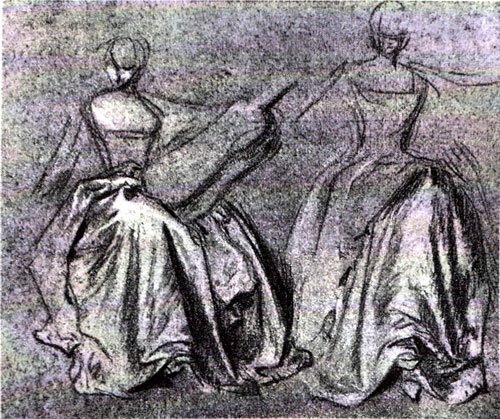

There are two drawings associated with the woman guitarist. One, a study in Amsterdam of the woman’s arm and guitar (Rosenberg and Prat 501), was employed with little change; it could be argued that it was made specifically for this painting because the distinctive position of the upright guitar is not seen elsewhere in Watteau’s oeuvre. A vigorous double study of a seated woman (Rosenberg and Prat R400) is more problematic in that this drawing, accepted by previous Watteau scholars including Parker and Mathey, was rejected by Rosenberg and Prat. Although not a pretty drawing, it has great strength and vitality, and lacks the characteristics of a copyist or Watteau imitator. It shows the artist trying out two alternative positions for the woman’s upraised knee and extended leg; he decided on the solution at the left for Le Conteur. Despite Rosenberg and Prat’s rejection of this study, subsequent scholars have justly continued to accept its authenticity.

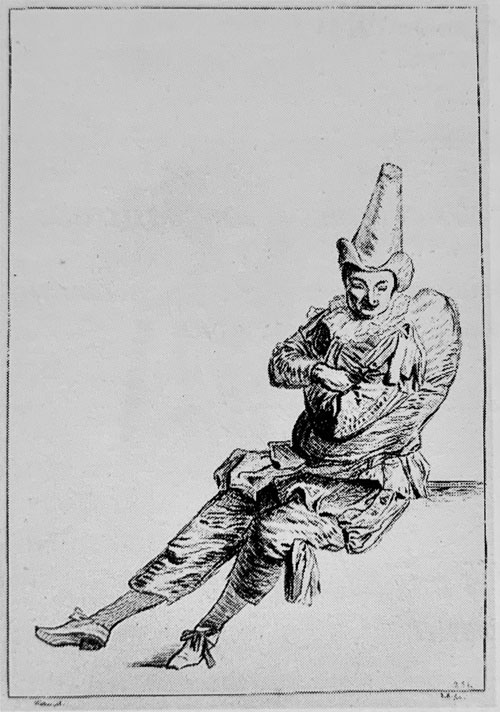

The most remarkable drawing associated with this painting is a compositional study in the Cleveland Museum of Art (Rosenberg and Prat R118). It is freely drawn, and although the kneeling actor was probably sketched from life, the other figures seem to have been done from imagination. rather than from a live model. As we have seen, the pose of the woman was already established in the double study in Amsterdam, and her basic lines were added around the kneeling Mezzetin. So too, the figure of Pierrot who leans over the group appears to have been drawn around the pre-existent figure of the woman and the Mezzetin. In this first rendering, his wide-brimmed hat covers his full face, but Watteau then redrew the head with greater specificity in the upper corner of the page, hiding his eyes. In the painting, Watteau removed the hat and replaced it with the comedian’s traditional skull cap, thus revealing the face fully. This is one of the few times in the latter part of Watteau’s career that we can follow the artist working out his composition on paper.

A handsome study of a man in a private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 400) was used by Watteau for one of the three figures set slightly behind. The drawing has been cut at the top, removing most of his head covering; when Boucher engraved this image for the Figures de différents caractères (plate 104), he portrayed it as a turban curiously rising to a peak, but Watteau painted it as a flat beret, with different folds in the fabric.

Not least, for the charming King Charles spaniel that sits inquisitively (and awkwardly!) between Mezzetin’s legs, Watteau turned to a sheet with four studies of this gently affable dog (Rosenberg and Prat 553), choosing the one in the upper register at the left.

REMARKS

Although this painting enjoys a substantially well-documented provenance, the period between 1839 and the time that it entered the Rothschild collection is not well charted. It has not been possible to confirm Adhémar’s claim that the painting was included in an exhibition at the Galerie Martinet in 1862. The suggestion made here that it is to be identified with the picture formerly in the Marcille and Riquet collections remains hypothetical because the measurements and support of the painting were not given in these mid-nineteenth century sales. Nonetheless, this history would help shed light on the picture’s whereabouts in this period.

Once the painting entered the collection of Edouard Rothschild it was not seen again publicly except immediately after World War II when some of the German war booty was put on display in Paris. Otherwise, experts have relied on old black and white photographs of the painting. Nonetheless, except for Adhémar, there was general confidence in the Rothschild painting; ironically, Adhémar who had the opportunity to examine the painting in 1946, seems to have rejected it—although her entry is confused and she does, in fact, list the composition as being in the Rothschild collection.

The reappearance and conservation of the painting in 2001 proved conclusively that the Rothschild picture was the original from Watteau’s hand. The cleaning and removal of repaint revealed the sensitive brushwork and color typical of Watteau. Also, infra-red investigation uncovered pentimenti of the sort we would expect from the way he worked out his design directly on the canvas. The most significant pentimento was discovered in the lower left corner of the composition: originally Watteau had painted a women seated on the ground there, turning and facing the viewer. She is drawn on the slightly smaller scale of the background figures and did not harmonize with the kneeling Mezzetin, which is undoubtedly why Watteau chose to eliminate her as the painting progressed.

As with all Watteau paintings, scholarly opinion about the dating of Le Conteur is not resolved. Mathey would date it early, c. 1713-15. Macchia and Montagni preferred 1715. Adhémar proposed mid-1716, as did Roland Michel. Rosenberg and Prat dated the Rijksmuseum’s drawing of the arm holding the guitar to c. 1716-17 whereas Grasselli proposed 1718 for the same study; it would follow that the painting could be no earlier than the preparatory drawings, which would mean that these last-mentioned scholars would date the painting somewhat later than earlier critics proposed.

Le Conteur is one of the most openly salacious of Watteau’s paintings. Mariette described the composition in a surprisingly nonchalant way: “un homme à genoux mettant le main sur le sein d’une femme qui tient une guitare, accompagnée d’un Pierrot, Mezetin & autres comédiens.” That the actor is actually touching, if not grasping, the woman’s exposed breast is shocking, especially since Watteau was normally discreet in such matters. Notwithstanding this physical contact, the woman seems unmoved. The poetic detachment that normally prevails in Watteau’s fêtes galantes is found here as well. Eighteenth-century sale catalogues frequently invoked the term “surprise” when describing the painting, but little of that emotion is expressed in her face or body; she shows little or no reaction.

Watteau, Le Conteur (detail).

Watteau, Gilles (detail), Paris, Musée du Louvre.

A word needs to be said about the identity of the comedians depicted. The actor in a red suit and wide beret in the midground is an infrequently seen character in Watteau’s oeuvre. He would seem to be the same character who appears in a similar pose at the right side of the celebrated Gilles in the Louvre, and who is generally identified as the braggart Captain. This character, otherwise, is remarkably absent from Watteau’s oeuvre.

Even more intriguing is the kneeling actor. He has generally been identified as Mezzetin because of his pink and blue suit, although its traditional striped pattern is only lightly indicated. While Mezzetin normally wears a soft cap, here he sports a very different sort of head covering. It has a tall, conical form, with a narrow brim and a large feather. This distinctive hat is normally worn by another clown, Punchinello. Yet Punchinello is a heavier-set man with a pronounced belly. This is the way he was portrayed in the artist’s Le Départ des comédiens italiens en 1697, and also in a drawing recorded in the Figures de différents caractères. In blurring the lines between these actors’ costumes, Watteau, the master of ambiguity, seems to have again worked his magic.

Click here for copies of Le Conteur