- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Coquettes qui pour voir

Entered January 2019; revised May 2022

St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, inv. no. GE1131.

Oil on panel

19 x 24 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Acteurs de la Comédie-Français

Acteurs du théâtre français

Les Coquettes

Coquettes qui pour voir galans au rendez-vous

Mascarade

Personnages en masque préparant pour le bal

Le Rendez-vous au bal masqué

Le Retour du bal

RELATED PRINTS

Henri Simon Thomassin after Watteau, Coquettes qui pour voir, 1741, engraving.

Watteau’s Coquettes qui pour voir was engraved in reverse by Henri Simon Thomassin prior to 1741. The print was cited in Bernard Lépicié’s obituary notice for Thomassin that appeared in the March 1741 issue of the Mercure de France.

Thomassin’s print was copied in manière noire by J. Simon (1675-1755) under the title “Mascarade.”

Francesco Bartolozzi after Watteau, Preparation for the Masquerade, c. 1785, engraving.

The turbaned woman at the left of Thomassin‘s engraving was engraved in London in 1785 by Francesco Bartolozzi (1735-1813). Set in an oval format, the image was captioned Preparation for the Masquerade with the misleading declaration “Watteau pinxt." It is reported that some copies of this Bartolozzi print bore the title “A Favourite Sultana.”

Félix-Jean Gauchard after Thomassin, La Comédie italienne, c. 1862-62, engraving.

Another engraving of the composition was produced, this by Félix-Jean Gauchard, to accompany the entry on Watteau in Charles Blanc’s Histoire des peintres des toutes les écoles. École français (Paris: 1862-63). Although the image was probably based on Thomassin’s print, it was renamed “La Comédie italienne.”

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Nicolas Bailly (1659-1731). According to Ernst, an old label on the reverse side of the painting specified that it came from Bailly’s collection. Zolotov et al. in 1981 referred to the collector as “N. Botz” which may be an error in transcription from French to Russian.

Paris, collection of Louis Antoine Crozat, baron de Thiers (1700-1770). The painting was in Crozat de Thiers' collection by 1746 according to the inventory prepared that year. It was cited in that collection by Dezallier d’Argenville, Voyage pittoresque, 1757, p. 140.

St. Petersburg, collection of Catherine II (1729-1796; empress of Russia). Purchased with the Crozat de Thiers collection, which was bought en bloc in 1772. At the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg c. 1875; by 1912 moved to the Gatchinova Palace; transferred to the Hermitage Museum after the Russian Revolution.

EXHIBITIONS

St. Petersburg, Starye Gody (1908), cat. 286.

Petrograd, Hermitage, Peinture française des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (1922).

Moscow, Pushkin Museum, French Art of the 15th-20th Centuries (1955).

Bordeaux, Musée, Chefs-d’oeuvre (1965), cat. 43 (by Watteau, Le Retour du bal [Les Coquettes ou Les Acteurs du théâtre français], lent by the Hermitage).

Paris, Louvre, Chefs-d’oeuvre de la peinture française (1965-66), cat. 41 (by Watteau, Le Retour du bal [Les Coquettes], lent by the Hermitage).

Leningrad, Hermitage, Watteau and His Time (1972), cat. 5.

Bordeaux, Galerie des beaux-arts, Arts du théâtre (1980), cat. 67 (by Watteau, Acteurs de la Comédie-Français, lent by the Hermitage).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P29 (by Watteau, Coquettes [‘Coquettes qui pour voir …’], lent by the Hermitage).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lépicié, “Lettre . . . à M. D. L. R.” (1741), 569.

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 192.

Dezallier d’Argenville, Voyage pittoresque, 1757, p. 140.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 30.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 30.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 78.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), cat. 78.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 71-72.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 182.

Schefer, “Les Portraits dans l’oeuvre de Watteau” (1896), 183-84.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures théâtrales" (1904) 345, 352.

Weiner, Lipphardt et al, Les Anciennes écoles de peinture (1910), 114.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), no. 122.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 36.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 107.

Ernst, “L’Exposition de peinture française” (1928), 172.

Barker, Watteau (1939), 133-34.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 154.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 162.

Stuffmann, “Collection de Pierre Crozat” (1968) 135.

Pouillon, Watteau (1969), pl. V.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 3: cat. B30.

Nemilova, Enigmas of Old Masters (1973), 133-51.

Zolotov, Watteau (1973), cat. 6Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 118.

Nemilova, La Peinture française (1982), cat. 45.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 217.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 255-56, 290.

Zolotov et al., Watteau (1985), cat. 8-11.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 44, 75, 135, 415, 417, 456, 608.

Zolotov, Watteau (1996), 86-95.

Börsch-Supan, Watteau (2000), 46-47.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 79, cat. 77.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Most of the five characters in Coquettes qui pour voir can be related to extant drawings, either directly or through comparable studies in Watteau’s oeuvre.

The young black man was based on a sheet of studies in the Louvre which includes three of this one figure (Rosenberg and Prat 415). The drawing shows just the head and the barest indication of his torso, and this deficiency is carried over into the painting where only the most rudimentary indications of his shoulders and torso are given.

The comic actor at the far right is generally associated with an early, small, full-length study of the same character; it unfortunately has been trimmed at the bottom (Rosenberg and Prat 75). However, that small, somewhat summary study is probably a reduced version of a larger, more vibrant study of the actor drawn from life, similar to other studies of the actor (Rosenberg and Prat 130 and 135). The sensitive rendering of the hand holding the cane and especially the portraitistic quality of the actor’s face suggest that Watteau relied on additional drawings for his painting.

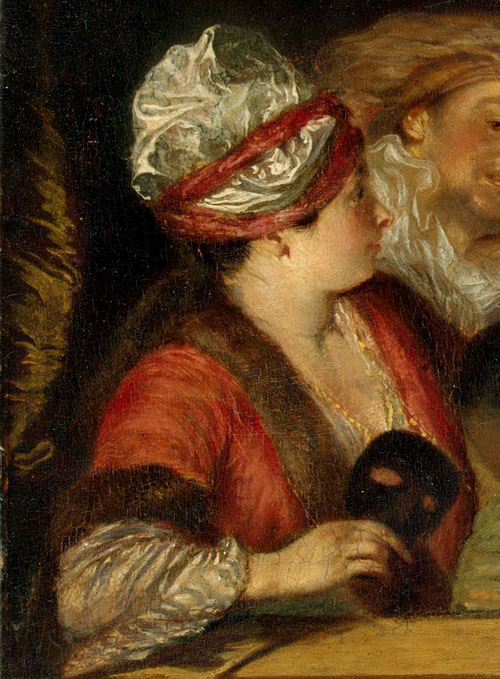

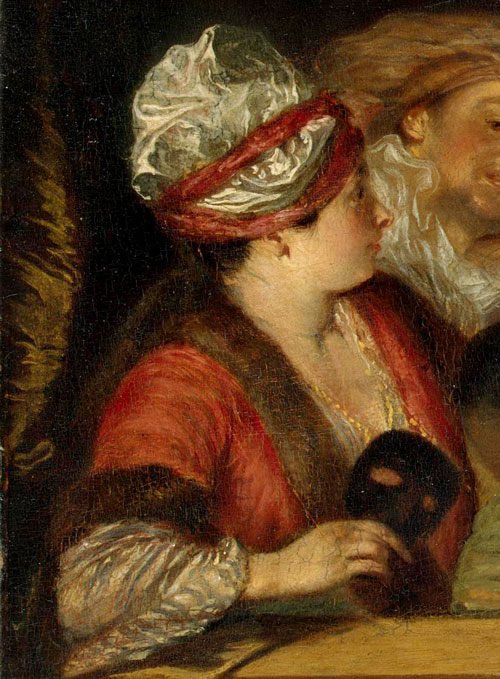

As in the preceding example, the actress at the left side of the painting has been related to an early, small, full-length study (Rosenberg and Prat 44). That drawing depicts a woman in the same distinctive costume: a loosely wrapped turban, as well as a short-sleeved jacket trimmed with fur around the neck, bodice, and on the sleeves. The drawing’s summary treatment of the subject makes it reasonable to presume that Watteau executed other, more detailed studies from the live model. One of these now-lost drawings would have served for his painting La Pollonaise assise, and another for Coquettes qui pour voir. Indeed, the woman in the painting is posed differently from the model in the early drawing; although the heads are set in profile in both works, the angles of the shoulders are reversed and, of course, the woman in the painting bends her arm to support her weight. Various studies of women’s hands holding masks have been related to this painting; the closest is a study in Berlin (Rosenberg and Prat 417), but even when reversed (which Watteau could have effected with a counterproof), the positions of the individual fingers and the angle of the mask do not match those in the painting.

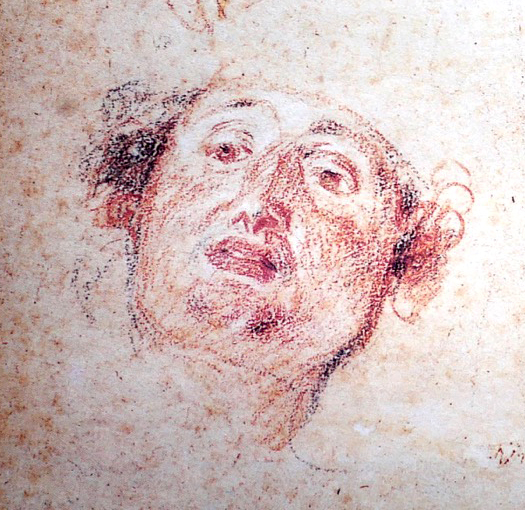

The head of Mezzetin, thrusting out from behind the seated woman, has been associated by Zolotov with a head on a sheet of studies in New York (Rosenberg and Prat 456). But the inclination is different, and the ear is not visible; this is not the head that appears in Coquettes qui pour voir. Rather, the drawing for this figure should be presumed lost; but something of it can be deduced by the same character’s appearance in Pierrot, Mezzetin, Scaramouche, Scapin et Arlequin, now in the Getty Museum, where his upper torso and arms are also revealed, and the tilt of his head is made understandable: originally he was passionately strumming a guitar.

REMARKS

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the titles assigned to this painting varied considerably. Lépicié called the picture Le Retour du bal, whereas d’Argenville preferred Des Personnages en masque se préparant pour le bal. Hédouin chose Le Rendez-vous du bal masqué. Beginning with Edmond de Goncourt, it has become customary to assign the painting the awkward name of Coquettes qui pour voir, the opening words of the two quatrains that appear under the Thomassin engraving.

Coquettes qui pour voir galans au rendez vous, Qu’en tel cas ne ferois que ce qu’on fait en France |

Coquettish women, who to meet gallant men go around at the ball despite their husband, In such a case, I would do what they do in France |

Notwithstanding these three competing descriptions of the painting—going to the ball, being at the ball, or returning from the ball—(different sides of essentially the same coin), these narratives agree that the people are not actual commedia dell’arte actors but, rather, ordinary men and women momentarily assuming those roles.

Watteau, Les Comédiens italiens, oil on canvas, 63.8 x 76.2 cm. Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1946.

Another possibility that has been advanced is that this painting represents the actors themselves and that it resembles Watteau paintings such as Les Comédiens italiens. The characters in Coquettes qui pour voir strike the poses assigned to their roles: Mezzetin with his head thrown back, Cassandre hunched over his cane, the soubrette looking sweetly innocent. In several iterations of her study of the painting, Nemilova has sought to identify not only the characters but also the specific actors assuming these roles. She would have us believe, for example, that Watteau portrayed Mlle. Desmares as the soubrette.

However, it seems unlikely that Coquettes qui pour voir represented contemporary French theater. Indeed, the woman at the left is not a standard theatrical personage. Her fur-trimmed robe and loose turban are the hallmarks of what was known as the Polish costume. The same attire, probably the same woman, is seen in Watteau’s La Pollonaise debout as well as in La Pollonaise assise and La Rêveuse. But the mask in her hand indicates she is a chic Parisian dressed for a ball.

Watteau, Coquettes qui pour voir (detail).

Watteau, Les Charmes de la vie (detail). London, Wallace Collection.

Likewise, the young black servant is not a stock character in the commedia dell’arte. Instead, he resembles the servants in several other Watteau paintings, such as Les Plaisirs du bal in Dulwich and Le Concert champêtre, a group portrait of the Bougi family. He especially resembles the servant in Les Charmes de la vie in the Wallace Collection. In that painting the young man's pose reflects his handling the wine bottles in a bucket, whereas in Coquettes qui pour voir his pose seems unjustified. He looks as if he is peering intensely at the balustrade.

As with so much of Watteau’s art, the subject of this painting remains ambiguous. Whether the group is going to a ball or returning from it, whether it is men and women dressed as commedia dell’arte characters or commedia actors themselves. Watteau’s intentions remain enigmas wrapped in mystery.

The painting in the Hermitage has a well-established pedigree, having been in the collections of Crozat de Thiers and Catherine the Great almost since its inception. Despite losses and restorations, it is in remarkably good condition. Only occasionally has the painting’s authenticity been questioned. Nicholas Wrangl, a curator at the Hermitage in the early twentieth century (cited in Zimmerman), pointed out supposed differences between the Hermitage painting and Thomassin’s engraving: the blond actress lacks the coiffure seen in the engraving, and there are differences in the actor at the right. Wrangl concluded that Mercier executed the Hermitage painting, but this is baseless: Mercier could not paint at the same level of excellence and there are none of Mercier’s personal characteristics. More recently, Ferré, ever the iconoclast and conspiracy theorist, tried to cast doubt, questioning why Dezallier d’Argenville mentioned the painting in the Crozat de Thiers collection in the 1756 edition of his guide to Paris, but suppressed the reference in the 1765 edition. He queried why Lazare Duvaux cited a painting of “deux personages en masque, par Watteau” in the Crozat collection, and Ferré quotes his colleague Saint-Paulien as opining that the Hermitage painting is a pastiche by Mercier. That opinion is impossible to accept.

Just as there is essentially universal acceptance of the Hermitage picture, so too there is surprising unanimity regarding the date when the painting was executed. Almost all scholars agree that the painting is from the artist’s mid-career, but the specific year remains a matter of conjecture. Roland Michel proposed c. 1712-14 and elsewhere as not earlier than 1714-15; Mathey chose 1713-15; Adhémar suggested 1716; Temperini proposed 1716-17; Nemilova, and Macchia and Montagni preferred 1717 (although later Nemilova chose a date closer to 1712); Rosenberg and Prat dated some of the preliminary drawings (e.g., their cat. 415) to c. 1715-16 , which would establishes a terminus post quem. Börsch-Supan was perhaps alone to date the work as late as c. 1718.

Click here for copies of Coquettes qui pour voir