- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

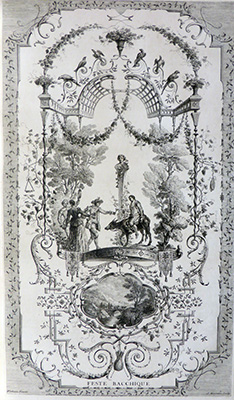

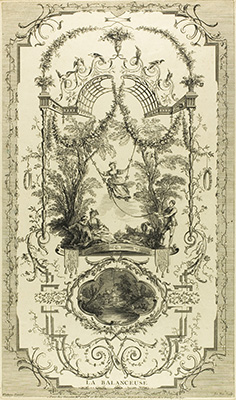

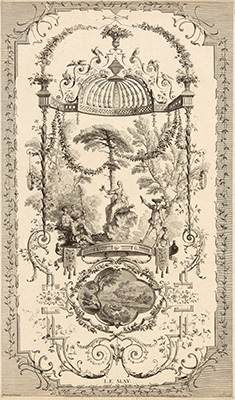

Décoration: Hôtel Chauvelin: Feste bacchique, La Balanceuse, Partie de chasse, Le May

Entered August 2025

Presumed lost

Material unknown

Dimensions unknown

RELATED PRINTS

This set of four arabesques (called "Chauvelin" after their first documented owner) was engraved c. 1731 by a team of four different engravers: Jean Philippe Le Bas for Feste bacchique, Jean Moyreau for La Balanceuse, Gérard Scotin for Partie de chasse, and Pierre Aveline for Le May.Althoughonly the print after Partie de chasse is dated 1731, the four were numbered (from 1 to 4, in that order) and announced for sale as a bound volume by Edme François Gersaint in the June 1731 issue of the Mercure de France (pp. 1564-65).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Germain Louis Chauvelin (1682-1762; Marquis de Grosbois, garde des sceaux, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs under Louis XV). According to Pierre Jean Mariette, “ces quatre grandes & riches compositions d’ornemens ont été peintes par Watteau sur les lambris du cabinet de M. Chauvelin, Garde des sceaux de France & Ministre d’estat.“ The paintings are not mentioned in his posthumous sale, June 21, 1762, which was conducted in his hôtel on the rue de Varenne.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, Notes manuscrites, 9: fol. 198.

Goncourt, L'Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 199-202.

Mantz, Antoine Watteau (1892), 27-28.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 83.

Fourcaud, “Watteau: Peintre d'arabesques” (1908-09), 50, 54, 55, 131.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), 120-21.

Deshairs, “Les Arabesques de Watteau” (1913), 289.

Dacier, “Les premiers amateurs de Watteau” (1921), 126.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 27; 2 : 34, 51, 62, 80, 84, 133 (note 2), 160 ; 3: cat. 98-101.

Rahir, Watteau, peintre d ’arabesques (1922), 9, 11.

Dacier, Watteau, dessinateur (1926), p. X .

Réau, ”Watteau” (1928), cat. 237-240.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 19.

Wunder, Extravagant Drawings (1962), cat. 54.

Macchia and Montagni, L'opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 47 A-D.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 191-94.

Posner, “Swinging Women” (1982).

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 292.

Eidelberg, “Huquier, Friend or Foe of Watteau?” (1984), 162.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), under cat. 2.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 61-62.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. R 382.

Eidelberg, “How Watteau Designed His Arabesques” (2003).

Eidelberg, “Watteau and Audran at the Hôtel de Nointel” (2002), 13, 15.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 137.

Eidelberg, “Watteau, A Good but Difficult Friend“ (2022), 45.

Rimaud, “Le pinceau limpide et fin” (2022), 197 (note 9).

RELATED DRAWINGS

The woman on a swing in La Balanceuse bears a resemblance to one in a drawing now in Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat ) This drawing, actually a counterproof, is one of a group of studies that Watteau sold in 1715 to the Swedish count, Carol Gustav Tessin (1695-1770), thus providing a firm terminus ante quem for the drawing. However, while the tilt of the woman’s head and the position of her arms are similar, the demure woman in the drawing sits unmoved whereas the skirts of her painted counterpart flutter and move with the wind and the action of the swing.

Jean Philippe Le Bas after Watteau, La Fête bacchique, 61.9 x 36.5 cm, red and black chalk. New York, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

No other Watteau drawings are considered preparatory to the Chauvelin arabesques. However, a large sheet in the the Cooper Hewitt Museum, executed in a distinctive mixture of red and black chalk, is directly related to Feste bacchique. It was traditionally attributed to Watteau by Wunder and others, but it is not by the master himself. More recently, it has been attributed to Jean Philipe Le Bas and is considered his study from Watteau’s original painting in preparation for his print. The dimensions of the drawing are very similar to those of the copper plate (59.6 × 35.2 cm), and the fact that it was squared also suggest that this drawing was commissioned to replicate the Chauvelin arabesque.

REMARKS

The first documented owner of this decorative program of four arabesques, Louis Germain Chauvelin, was an important politician and collector of his time. Chauvelin owned La Lorgneuse and L’Accord Parfait by Watteau. Mariette’s comment states that these arabesques were “painted by Watteau on the boiseries of the cabinet of M. Chauvelin, Garde des sceaux de France and state minister.” Mariette does not specify which of the several residences that Chauvelin owned housed these decorative schemes. He lived successively on rue de Richelieu (until 1719), in the rue des Saints-Pères (1719-1742), rue de l'Université (at least by 1746), and rue de Varenne (until 1762). Given the apparent early style of Watteau’s paintings here, definitely before 1719, as well as the fact that Watteau traveled to London in 1719, one is obliged to conclude that these arabesques were made for the home on the rue des Saint-Pères.

Although we do not know the measurements of theses arabesques, Mariette’s affirmation that they were “grandes & riches compositions” suggests that their dimensions were substantial.

The decorative strategies that constitute the major part of these arabesque panels are complex. The individual components— trellises, urns, graceful rinceaux— build on the ideas of Claude III Audran, with whom Watteau worked. As Eidelberg (2002) has observed, it is likely that this cycle was not solely Watteau’s responsibility and that Audran was involved. In fact, it is more likely that Chauvelin would have gone to Audran, and Audran might well have subcontracted the project to his young and still uknown assistant. Certainly, Audran would have been in a better postion to receive such a commission from this prominent patron. Significantly, Chauvelin called again upon Audran in 1731, commissioning him to decorate his newly purchased château at Grosbois, close to Paris (see Paris, Archives Nationales, MC/ET/XLIX/553, paper no 30: “une autre minute et mémoire d’ouvrages faits par ledit Sieur Audran pour Mgr le garde des Sceaux en son chateau de Grosbois” cited in Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs, 1921-29,1: 27).

Even if the commission for the Chauvelin arabesques went first to Audran, and if the ornamental elements of these arabesques are dependent on Audran’s vocabulary, the central scenes above the medallions—figures dancing, a woman on a swing, a huntress at a hunt—are just the types of subjects that were Watteau’s forte as a “peintre de fêtes galantes.”

Claude Gillot, Scene from “The Tomb of Master Anadré” (detail), red chalk, watercolor, and pen and black ink over graphite. Washington, D.C., The National Gallery of Art.

Antoine Watteau, Gilles (detail), oil on canvas, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Jean Philippe Le Bas after Watteau, Feste bacchique (detail), engraving.

Jean Jacques Spoede, Triumph of Silenus (detail), oil on canvas. Paris, collection FM.

The iconograhy of the scenes at the centers of the Chauvelin arabesques, although seemingly secondary, is worth considering. The figure of a comedian on the back of a donkey—as in Feste bacchique—can be found in several works by Watteau and his circle—scenes dealing with revelry and drinking. Claude Gillot included this motif in his drawing of a scene taken from the commedia dell’arte play, Le Tombeau de Maître André. Here, Harlequin on a donkey is pulled by attendants, and a similar narrative appears in Watteau’s Gilles. Though not pulled by his attendants, Watteau’s comedian on the back of the donkey in Feste bacchique also bears a resemblance to one painted by Jacques Jean Spoëde, yet another collaborator in Claude Gillot’s workshop.

Other analogies for the Chauvelin arabesques can me established with drawings by Watteau. For example, the huntress and her pack of dogs in Partie de chasse resembles a Watteau drawing in Frankfort (Rosenberg and Prat 194). Gabriel Huquier included a similar figure in his engraving, La Chasseuse., an arabesque he claimed was by Watteau though it may have been more his invention than Watteau’s. Nonetheless, it shows that Parisians accepted the idea that a huntress and her dog was appropriate for the decoration of a room.

Watteau, L’Escarpolette, oil on canvas, 95 x 73 cm. Helsinki, Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, inv. A II 1413

Watteau turned to the theme of a woman on a swing in another of his arabesques, L’Escarpolette, the central portion of which is preserved in the Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki. Moreover he often included this theme in his fêtes galantes, such as Les Bergers in Berlin and Les Agréments de l’été.