- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

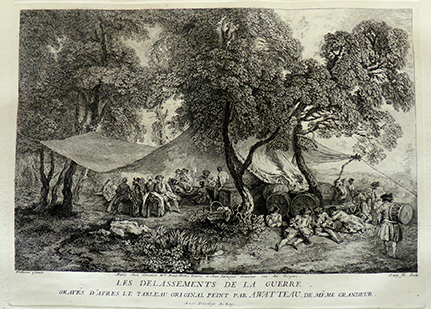

Les Délassements de la guerre

Entered April 2020

St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, inv. ГЭ-1162. .

Oil on copper

22 x 33 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Bivacco di Soldati

A Break in the Action

Diversions from WarHalte

Idylls of War

The Respite from War

RELATED PRINTS

Louis Crepy fils after Watteau, Les Délassements de la guerre, 1731, engraving.

Les Délassements de la guerre was engraved by Louis Crepy fils in 1731; but the pendant picture, Les Fatigues de la guerre, was engraved at the same time by Jean-Baptiste Scotin. Both were announced for sale in the June 1731 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 1564).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Antoine de La Roque (1672-1744; military officer, newspaper publisher). His sale, Paris, April 1745, lot 44: “Deux des plus piquans Tableaux que Vatteau ait peint; ils sont sur cuivre, ils portent douze pouces & demi de large sur douze pouces de haut; ils représentent des Sujets de Guerre; je les ai fait graver sous les Inscriptions des Fatigues & des Délassemens de la Guerre, par M. Crepi. Ils sont très-purs, extrêmement finis, & en même-tems touchez avec tout l’esprit & toute la finesse dont Vatteau étoit capable.” Sold for 680 livres to Edme Gersaint for the account of the marquis de Calviere (according to the Getty Research Institute).

Paris, collection of Louis Antoine Crozat, baron de Thiers (1700-1770). The painting was cited in situ in Dezallier d’Argenville, Voyage pittoreasque de Paris, 3rd. edition (Paris: 1757), 137 Une Marche de Troupes & une Halte; deux petits ouvrages de Watteau . . . .” Crozat’s collection was sold en bloc to agents of Catherine the Great of Russia in 1777.

St. Petersburg, collection of Catherine II (1729-1796; empress of Russia).

EXHIBITIONS

Moscow, Pushkin Museum, French Art of the 15th-20th Centuries (1955), 24.

Leningrad, L’Art français des XIIe-XXe siècles, (1956), cat. p. 12

Bordeaux, Musée, Chefs d’oeuvre (1965), cat. 45 (as by Watteau, Les Délassements de la Guerre, lent by the Musée de l’Ermitage).

Leningrad, Hermitage, Watteau and His Time (1972), cat. 6.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 16.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 192, no. 24.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 56.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1854), cat. 57.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 55.

Mollett, Watteau (1883), 62.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 27.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), no. 30.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 122; 2: 83,133, 157, 162, 264; 3: cat. 216.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 43.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 95.

Sterling, Great French Paintings (1958), 40-41.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 67.

Cailleux, “Four Studies of Soldiers” (1959), v, vii.

Mongan, “Three Views of a Drummer” (1964), 43.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 13-16.

Martin-Méry, Chefs-d’oeuvre de la peinture française (1965) cat. 45.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 96.

Stuffman, “Collection Crozat” (1968), cat. 186.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A5.

Nemilova, Watteau and His Time (1972), cat. 6.

Zolotov, Watteau (1973), cat. 3

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 138.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 96-97, 113, 167-69, 265, 269.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 38-39.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), under cat. 26.

Zolotov et al., Watteau (1985), 105.

Nemilova, French Painting of the XVIII Century (1985), cat 33.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 179, 180, 210, G97

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 32.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 96.

Wile, Watteau’s Soldiers (2016), 41-42, 60, 62, 87, 98, 94.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Like all of Watteau’s military paintings, Les Délassements de la guerre depended upon his studies from the model. The drummer at the far left of the picture was based on a triple study of a drummer now in the Fogg Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 210), Watteau chose the rightmost figure for the painting.

From one sheet now in Rotterdam (Rosenberg and Prat 180), the artist took all four soldiers and largely kept them in sequence when transferring them to the painting. Starting at the top with the soldier who is extended full length, then the two soldiers with muskets across their laps, and finally the half-length of a soldier in the lower right corner of the page who holds his hand to his cheek—all these men appear in that order in the left foreground of the painting. Once again, we are reminded of how economically and carefully Watteau exploited his resources.

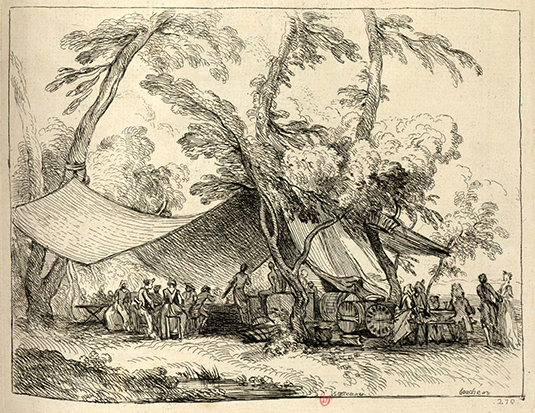

François Boucher after Watteau, Military Encampment (reversed to original direction of the drawing), engraving, Figures de différents caractères, plate 270.

While in the field, Watteau evidently made studies not only of the soldiers but also of their camp sites. One of these drawings, now lost, is recorded in plate 270 of the Figures de différents caractères. The artist used this drawing as the basis for the setting of Les Délassements de la guerre. If one considers just the tent and not the groups of figures, one can see the relationship: In both the tent extends to the far right of the composition and leaves a small space at the left. Also, the dips and peaks in the tent are the same. However, the figures in the painting do not mirror the rapidly drawn indications in the drawing. When Watteau drew this composition was he merely recording what he saw or was he already planning a painting of the subject? This is difficult to answer. But Roland Michel’s theory that he was recording the painting from memory is unlikely since it does not correspond to the artist’s known practice; moreover, the women wear fontange headdresses in the drawing but not in the painting, marking not only the change in women’s fashions but also the priority of the drawing.

REMARKS

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold claimed that the painting had been owned by Edme Gersaint before it entered La Roque’s collection but these scholars, normally scrupulous in documenting such matters, seem not to have done so in this instance. Gersaint was briefly involved with this painting and its pendant when they were sold from La Roque’s collection but there is no evidence that Gersaint owned it previously. In any event, the provenance from La Roque to baron de Thiers, and then on to Catherine the Great is unbroken. Few Watteau paintings can claim such an unbroken pedigree.

Given the painting’s excellent provenance, no critics have doubted its autograph nature. On the other hand, there is little agreement as to when Watteau painted it, and ranges from 1711 to 1716—which is a considerable span of years in relation to the brevity of Watteau’s career. Moreover, there is no correlation between the date proposed and when the opinion was rendered. Glorieux, one of the most recent scholars, suggested 1711; Mathey preferred 1712; Rosenberg preferred 1712-13; Wile decided on 1713-14; Macchia and Montagni assigned the painting to 1714; Adhémar listed the work for 1712-15 but seems to have favored a date close to 1715; Roland Michel first declared for 1714-15 but a few years later wrote that the painting could not have been executed later than 1712-13; Grasselli and Temperini favored 1714; Sterling and Posner claimed 1714-15; Zolotov and Nemilova opted for 1715; finally Martin-Méry selected 1715-16, which is the latest date proposed.

Watteau and Antoine de la Roque, the first owner of the painting, evidently knew each other well. Watteau painted La Roque’s portrait and, in turn, La Roque commemorated Watteau in the obituary notice of the artist that he printed in the Mercure. It is fascinating that of all Watteau’s paintings, he chose these two military subjects. La Roque had been a constable of the Royal Guard but at the September 1709 Battle of Malplaquet a cannonball smashed his leg. As a result the leg had to be amputated, and thus Watteau portrayed him with his leg raised and a crutch beside him. Yet, despite his injury, La Roque, ever the pensioned ex-officer, chose military subjects to remember his military career.

The prominence given to the tent in Les Délassements de la guerre is singular within Watteau’s oeuvre. Small or partial views of tents appear in some of Watteau’s other military scenes such as Camp volant, Escorte d’équipages, and Détachement faisant halte. On the other hand, Watteau’s satellites, especially Pater and Lancret, painted many scenes in which these canteens were central motifs. A concomitant aspect of the setting is the prominence given to the women who joined the soldiers at these camps. Their presence can be discerned in Watteau’s preliminary drawing, where the women sit under the tent and also stroll about, but they do not have a particularly prominent role. It should be noted that in the drawing they all wear the fashionable fontange headdress but not in the painting, proving the anteriority of the drawing. Occasionally Watteau placed fashionably dressed women in the foreground of his other military scenes, as in Le Départ de garnison and L’Alte, but his followers frequently chose to emphasize such feminine aspects in these scenes of masculine life.

For copies of Les Délassements de la guerre CLICK HERE