- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Départ des comédiens italiens en 1697

Entered May 2020; revised April 2021

Presumed lost

Materials unknown

Measurements unknown

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

The Closing of the Comédie-italienne

The Departure of the Commedia dell'Arte from Paris in 1697

Partenza dei comici italiani nel 1697

RELATED PRINTS

Louis Jacob after Watteau, Le Départ des comédiens français en 1697, 1729, engraving.

Le Départ des comédiens français en 1697 was engraved in 1729 by Louis Jacob. It was announced for sale in the July 1729 issue of Mercure de France, pp. 1603-04. The engraving is apparently in the reverse direction of the painting.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of the abbé Penetti (secretary to abbé Franchini, Tuscan envoy to the French court).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: 193.

Hédouin, “Watteau” 1845, cat. 75.

Hedouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 76.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 70.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 14.

Dilke, French Painters (1898), 75-76.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 3, 155.

Wyzewa, “Une biographie anglaise de Watteau” (1903), 461.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures théâtrales” (1904), 137-38.

Gillet, Un grand maître (1921), 118-19.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 184.

Boucher, “Un Tableau inconnu” (1927), 66-73.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 178.

Populus, Gillot (1930), 24-25.

Barker, Watteau (1939), 32.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 8.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 66.

Gauthier, Watteau (1959), 7.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 8.

Ferré, Watteau, 1972, cat. B6.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 13.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 173.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 49.

Moureau, Présence d’Arlequin (1992), 29-32.

Crow, “Watteau Paints His First Theatrical Subjects” (1994), 402-03.

Plax, Watteau and Cultural Politics (2000), 7-52.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 45.

Ravel, “Trois images de l’expulsion” (2013).

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), cat. 24.

Plax, The Departure of the Commedia dell'Arte" (2018), 52-74.

RELATED DRAWINGS

There are no Watteau drawings directly related to Le Départ des comédiens italiens en 1697.

REMARKS

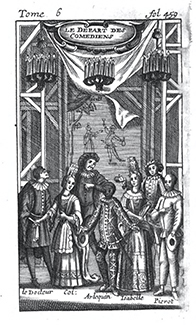

The unusual subject of Watteau’s composition is the historical event that too place in May 1697 when the troupe of Italian comedians in Paris was evicted by a royal decree from its home in the Hôtel de Bourgogne, a site that it had occupied since 1660. At the right side, a youth on a ladder posts the decree closing down the theater, and a magistrate gestures for them to leave. Crowding the foreground, the comedians—all in the traditional costumes of their roles—lament their fate in exaggerated theatrical poses.

It has become customary to acknowledge that Watteau could not have witnessed this event firsthand since he did not arrive in Paris until 1702, some five years after the expulsion took place. Surprisingly, most critics who have wanted to explain Watteau’s knowledge about this historic event have turned to Gillot as a possible source since he had been in Paris then. In fact, since the late nineteenth century, Dohme and a great many subsequent scholars have suggested that the painting was a collaboration between Gillot and Watteau, with the older artist supplying the first ideas for the composition and the younger artist refining the picture and executing it. Boucher and Gillet also proposed this idea, and the thesis of a collaboration has been continued forward by Adhémar, Roland Michel, Posner, Macchia and Montagni, Ravel, Plax, and many others. However, there is no evidence whatsoever that Gillot had a hand in designing the composition, just as there is no reason to assume that this was a collaboration.

In fact, Watteau may not have been depicting the historical event but, instead, the event as it was later staged in the French theater. A comedy about the expulsion of the Italian players was included in Le Théatre italien de Gherardi, in both the 1701 and 1714 editions. Evidently, the play and the event still had currency in Watteau’s era. Frontispieces illustrating the staging of this scene appeared in two editions of the play but, alas, both are dull and inanimate. They would have offered Watteau little or no inspiration. Moreover, the 1714 version was probably printed after Watteau had painted his picture.

Anonymous French artist, The Departure of the Italian Comedians in 1697, oil on canvas. Le Havre, Musée d'art moderne André Malraux.

Anonymous French artist, The Departure of the Italian Comedians in 1697, oil on canvas. Paris, Musée Carnavalet.

There are also two closely related but unfortunately anonymous paintings that show the same scene of the comedians’ departure, and these support the idea that the subject was popular. Given that most of the characters in the one painting correspond exactly to their counterparts in the other, it seems likely that the one is based on the other, and that both were perhaps painted by the same artist. These representations are more narrative in approach than the Gherardi frontispieces. By comparison, Watteau’s scene is a burlesque representation of the historical event as it might have been played on the comic stage, the characters displaying their characteristic, role-assigned pose.

Watteau, Scene with Commedia dell’arte Characters (detail), red chalk. Darmstadt, Hessisches Landesmuseum.

Watteau, Scene with Commedia dell’arte Characters (detail), red chalk. Whereabouts unknown.

Watteau, Harlequin (or Pulcinello?) (detail), red chalk counterproof, 18.3 x 15.3 cm. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum.

Did Watteau turn to his repertoire of drawings of these theatrical characters and assemble them on his canvas? A sizable number of studies illustrate the point: weeping actresses, a bowing, scraping Harlequin, even a strutting Pulcinello. Curiously, the characters do not cohere in Watteau’s composition. They lack interaction, focus, and narrative direction. All this is unusual, even in Watteau’s earliest works, and certainly argues against any claim that Gillot, skilled in depicting theatrical scene, was responsible for the overall design.

Almost all Watteau scholars believe that Le Départ des comédiens italiens en 1697 was executed in the first years of the artist’s career. Staley claimed that Watteau made a “sketch” of the composition in 1697, while he was still in his natal town, preserved in the Valenciennes Musée des beaux-arts; it was this sketch that Jacob engraved. Equally misguided, Phillips thought the picture was painted after the recall of the Italian Comedians in 1716; presumably because otherwise Watteau would not have known what the actors and their costumes looked like—a frivolous objection since in the interim the French comedians took over these roles and, as Watteau’s early drawings and paintings amply demonstrate, he was well acquainted with the comedic theater.

These eccentric arguments aside, most critics have opined that Watteau painted the work early in his career, perhaps even while he was in Gillot’s studio. Adhémar dated the picture to the years between 1703 and 1708, closer to the 1703 portion of the scale. Mathey dated it 1704-05, nearer to 1705. Macchia and Montagni centered on 1705. Posner agreed that it was possibly made while in Gillot’s studio. Roland Michel opted for 1706-08. Because the work does not truly resemble Watteau’s other early paintings, however, any attempt to date it faces insurmountable obstacles.

Plax’s recent interpretation of Watteau’s oeuvre seeks to show that Watteau was subversive and anti-royalist. Some of her argument rests on Le Départ des comédiens italiens and the traditional account that Louis XIV banished the Italian troupe because it staged a play, La Fausse Prude, an attack on Madame de Maintenon, Louis XIV’s morganatic wife. By chosing the subject of the Italian troupe’s expulsion, Plax claims that Watteau was also attacking the regime. However, critics such as François Moureau have dismissed the tale of La Fausse Prude being the reason for the comedians’ banishment. Moreover, Watteau was hardly anti-royalist or subversive. As the close friend of the comte de Caylus, a nephew of Madame de Maintenon, and as a member of the Regent’s circle, Watteau can hardly have been a subversive agent working against the court.

Click here for copies of Le Départ des comediens italiens en 1697