- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

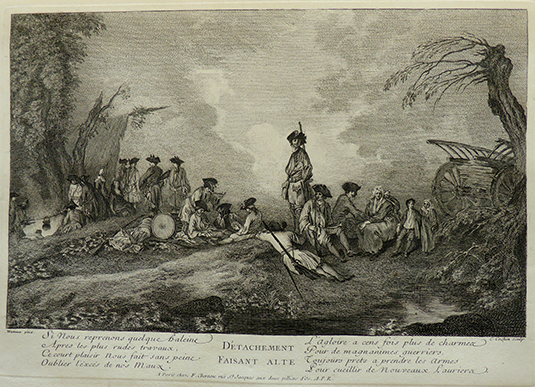

Détachement faisant alte

Entered July 2020

Presumed lost

Medium unknown

Measurements unknown

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Halt of a Detachment

RELATED PRINTS

Détachement faisant alte was engraved by Charles Nicolas Cochin in the same direction as the painting. The engraving of the composition was commissioned by the art dealer Pierre Sirois, who owned the painting, although this is not stated on the engraving. The engraving plate passed to Jullienne in 1729, and the print was incorporated into the Oeuvre gravé. Earlier on Watteau had made an etching of the pendant, Recrue allant joindre le régiment, and that plate, finished with the burin by Cochin, likewise was incorporated in the Oeuvre gravé.

PROVENANCE

Ordered by Pierre Sirois (1665-1726; art dealer and glazier), for which Watteau was paid 100 livres.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes Manuscrites,” 9: fol. 192.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 5.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 6.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 51.

Phillips, “The Picture Gallery of the Hermitage” (1900), 606.

Staley, “Eighteenth Century Art” (1902), 120.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 102.

Valotaire, «La recrue» (1919), 401-02.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), I: 34, 37, 175-76, 264; II: 22, 31, 32, 65, 66, 92, 122, 131, 135, 161; III: 62, 72, cat. 179.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 39.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 70.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 67, cat. 116.

Cailleux, “Four Studies of Soldiers“ (1959).

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 55.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B4.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 94.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 38, 167.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 34.

Rosenberg, Vies anciennes de Watteau (1984), 33-34.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), under cat. 179.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 38, 39.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 92.

Wile, Watteau’s Soldiers (2016), 45, 60, cat. 50.

RELATED DRAWINGS

The central figures in Watteau’s painting can be traced to two drawings. The standing soldier was derived from a drawing now in the collection of Professor Donald Stone (Rosenberg and Prat 61). The soldier lying on the ground, his back to the viewer, and the soldier next to him were taken from a sheet with four studies of soldiers (Rosenberg and Prat 67). These two soldiers were adjacent to each other in the drawing, but when taken over into the painting, their relative positions were reversed so that the recumbent soldier was at the left. It should be noted that in both cases, the drawings and the engraving agree in direction. This reinforces the idea that the painting was engraved in the same sense as the canvas.

REMARKS

The origin of this painting is linked to a narrative found in Gersaint’s biography of Watteau. After gaining only second prize in the Academy’s 1709 Prix de Rome, Watteau wanted to return to Valenciennes but lacked sufficient funds for the trip. Through his friendship with the painter Jean Jacques Spoede, he sold a small military subject to the art dealer Pierre Sirois, who then went on to commission a second painting, and paid the artist sixty livres. Watteau executed the second painting in Valenciennes and sent it back to Paris. Although Gersaint did not name the two paintings, he noted that they were engraved by Cochin. This admirably suits Détachement faisant alte and Recrue allant joindre le régiment, both engraved by Cochin. The disparity in scale and format between the two pictures reinforces the idea that they were not created at the same moment, nor even in the same locale.

The dating of Détachement faisant alte hinges on when Watteau made his return trip to Valenciennes. The picture previously was dated c. 1709—the assumed date of the trip. We now know that Watteau did not receive a passport to travel until late 1710, and therefore the execution of the painting must be redated accordingly. Some may quibble as to which pendant was created first, but the difference is insignificant. There is no reason to doubt the above narrative, especially since Mariette, the first to tell the tale, was Sirois’ son-in-law. Some of Watteau’s biographers such as Adhémar have written that Gersaint owned the pendant military paintings but this claim appears undocumented. Despite Mariette’s first-hand account, which is quite specific, much erroneous material has crept into the narrative. Adhémar, for example, claimed that Gersaint ordered the painting from Watteau, an idea repeated by Macchia and Montagni. When the paintings were engraved, no indication of ownership was indicated in the captions.

Beginning at least as far back as Hédouin in 1845, some critics sought to trace the provenance of Détachement faisant alte back to a Watteau painting sold from the prince de Conti collection on April 8ff, 1777, lot 665: “Une Alte d’infanterie: on y voit trois femmes, dont une Vivandiere.” That description better suits L’Alte, where three women figure prominently in the foreground. Although three women appear in Détachement faisant alte, two of them are in the background and barely discernible. Edmond de Goncourt wrongly thought that Détachement faisant alte had been in the collection of Louis Antoine Crozat, baron de Thiers, and this idea still had currency in the early twentieth century (Burlington Fine Arts Club exhibition, 1913). It was corrected by Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, who pointed out that the Thiers painting was actually Les Délassements de la guerre, now in the Hermitage. We are left, then, without a clue as to where Détachement faisant alte was for most of the eighteenth century.

Click here for copies of Détachement faisant alte