- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

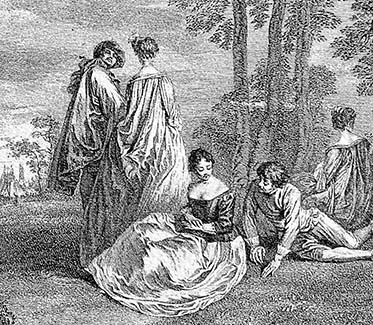

Les Deux cousines

Entered November 2021; revised February 2024

Paris, Musée du Louvre, RF 1990-8

Oil on canvas

30.4 x 35.6 cm.

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Le due cugine

RELATED PRINTS

Bernard Baron after Watteau, Les Deux cousines, 1729-31, engraving.

Watteau’s Les Deux cousines was engraved in London by Bernard Baron and was incorporated into Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé.

PROVENANCE

London, collection of Bernard Baron (c. 1696 -1762; engraver). Baron’s ownership of the painting is indicated on the engraving in Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé: “Tiré du Cabinet de Mr. Baron en Angleterre.”

Paris, anonymous sale, May 2-3, 1833, lot 110: “DU MEME [WATTEAU (Antoine)].-- Jolie composition d'une couleur claire et transparente, et touchée avec une finesse et une légèreté sans égale, représentant un jeune cavalier faisant la conversation avec deux jeunes personnes. T. 1.15 p., h. 11½.”

Paris, collection of Théodore Patureau (1798-1876; banker, honorary member of the Académie royale d'Anvers). His sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, April 20-21, 1857, lot 64: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE). LES DEUX COUSINES. Petite composition qui nous transporte au milieu d’un parc magnifique, dont les arbres aux rameaux élevés se détachent sur un beau ciel parsemé de quelques légers nuages. Un cours d’eau traverse de droite à gauche ce site enchanteur, embelli de statues et animé par quelques figures, parmi lesquelles se remarque un groupe de trois personnages place à la droite de la composition.

Une jeune personne, à la taille svelte et dégagée qui dissimule en partie une longue robe de soie couleur lilas, et dont la chevelure relevée est orné de fleurs et de plumes, regarde au loin à l’horizon. Elle est debout, et à ses pieds se trouve un gentilhomme présentant dans les plis de son manteau des fleurs à une jeune fille assise auprès de lui.

Celle-ci vient d’accepter une rose, qu’elle attache à son corsage en signe d’acquiescement aux sentiments affectueux que lui témoigne le jeune homme.

Gravé par BARON, sous ce titre: Les deux cousines. H. 29 cent. L. 35½ cent. Toile.” According to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Bibliothèque nationale, and Cousin, Le Tombeau de Watteau (1865), the painting sold for 550 francs to Van der Hoeven. The Archives de Paris, Études Pillet, Minutes 20-21 April 1857, indicate that the painting was bought by Madame van der Hoeven, 47 rue Saint Georges.Paris, collection of Madame van der Hoeven.

Paris, collection of Monsieur D. His sale, Paris, Hôtel des commissaires-priseurs, December 16-17, 1861, lot 54: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . Causerie dans un parc; sujet connu sous le titre des Deux Cousines. Gravé par Baron.” Sold for 292 francs.

Paris, collection of Henri Michel-Lévy (c. 1844/45-1914; artist and dealer). According to René Gimpel, Michel-Lévy sold the painting in September 1918 to Paul César Helleu for 220,000 francs.

Paris, collection of Paul César Helleu (1859-1927; artist)

Paris, collection of the comtesse de Béhague (1850-1939) by 1922.

Paris, collection of Hubert, marquis de Ganay (1888-1974).

Paris, private collection.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, acq. 1990 with funds from Mme. Granday-Prestel and an anonymous donor.

EXHIBITIONS

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Het franse Landschap van Poussin tot Cezanne (1951) cat. 138.

Geneva, Musée d’art, De Watteau à Cézanne (1951), cat. 68 (as by Watteau, Les Deux cousines, lent by private collector [Heugel?].

London, Royal Academy, European Masters of the Eighteenth Century (1954-55), cat. 245.

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André, Hommage à Louis Gillet (1976-77), cat. 28.

Paris, Musée de la monnaie, Pèlerinage (1977), cat. 39

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P 47.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 193.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 92.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 93.

Blanc, Le Trésor de la curiosité (1857), 2: 535.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Cousin, Le Tombeau de Watteau (1865), 32.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 124.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 68.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 178.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures galantes” (1905), 106-07.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912),83.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 93, 94, 99; 2: 96, 122, 131, 143; 3: cat. 146.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 106.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 140.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 69.

Mirimonde, “Les Sujets musicaux“ (1961), 269.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 151.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A 19.

Cailleux, “A Strange Monument” (1975), 247-48.

Eidelberg, “Watteau Paintings in England“ (1975), 578.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 188.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 89, 185.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 176.

Rosenberg. “Un chef-d’œuvre“ (1990), 259-262.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 328, 380, 398, 519, 551, 528.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 71-71, cat. 69.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 149.

Gimpel, Journal (2011), 91.

Sahut, Martin, and Sindaco-Domas, “Les Deux Cousines” (2009-10), 153-59.

Vogtherr, Preti, and Faroult, Delicious Decadence (2014), 24.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Several beautiful drawings from the model are associated with Les Deux cousines.

The standing woman in the painting, poetically isolated, was based on a figure on a sheet with three studies of the same model, two standing and one seated (Rosenberg and Prat 380). In the painting she is magisterial whereas in the drawing she is lovely but earthbound, as the artist fusses with the folds and stripes of her dress.

For the figure of the woman seated on the ground, pulling slightly to the side as she presses some of her suitor’s flowers to her breast, Watteau relied on a drawing in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 528). In comparing the two, the woman in the drawing seems slightly ampler in form and whereas in the painting her skirt swells and balloons out.

The gallant courtier in the painting, offering his flower-filled cape to his sweetheart, has been likened to a red chalk study of Mezzetin in the National Gallery of Canada (Rosenberg and Prat 551). However, while quite similar, the figures show significant differences. In the drawing, the actor wears a beret, the left side of his cape is lower than in the painting, his left shoulder is less visible, his right hand is further to the side, and his cape rests more naturally on his shoulder. Despite the many differences, this drawing may have been Watteau's starting point.

REMARKS

The early provenance of this painting is problematic. It was first owned by the engraver Bernard Baron, who was living in London when Watteau visited the British capital in 1719-20. It has been presumed that Watteau gifted the painting to Baron, his junior by a decade. For critics who think that the picture was painted in 1716, this would mean that Watteau brought the already-finished painting to London. However, it would be easier to assume that Watteau arrived unencumbered in London and that he executed the painting there. Mathey alone thought that, but he may not have been wrong. Watteau’s chronology is always a matter of dispute and the shading of a year or two is common.

In 1729 Baron returned to Paris for a brief stay and he must have brought his Watteau painting with him. This would explain how the picture came to appear on the French market just a few years later. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold were the first to identify it with a picture that appeared in an anonymous Paris auction in 1733. There it was specifically identified as Les Deux Cousines, its measurements correspond to the existing panel, and it description—down to the lilac color of the standing woman’s gown—is correct. Adhémar made no reference to the 1733 sale, whereas Macchia and Montagni did, but they tempered their response by adding “perhaps” in that sale. In 1984 Rosenberg wrote evasively that the painting is sometimes identified as the one in the 1733 sale, but carefully avoided accepting or rejecting this provenance.

Les Deux cousines then disappeared from sight for more than a century, not reappearing until the 1857 sale of the Patureau collection. According to the many annotated copies of the sale catalogue (one in the Bibliothèque nationale, six in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Dokumentatie, one in the Philadelphia Museum of Art), the painting sold for 550 francs to Van der Hoeven. The low price it achieved was due to doubts entertained at the time that it was not Watteau’s original picture. A contradictory account was offered by Cousin, who in 1865 (less than a decade after the Pateareau sale) wrote that the painting brought only a modest price but misprinted the number as 55,000 francs. In 1905, Fourcaud also recorded a price of 55,000 francs but recognized that was a very high price. Neither man was correct. The painting sold for the modest price of 550 francs. Elements of this confusion became embedded in the accounts of subsequent Watteau scholars, including Adhémar, Macchia and Montagni, Ferré, and Rosenberg’s text in the 1984 tercentenary catalogue.

Confounding things further, Fourcaud reported that Michel-Levy found the painting in an antique shop in the outskirts of London. But as the painting, fully recognized as a work by Watteau, appeared in the 1857 sale of the Patereau collection, a well-known and respected collection that had been previously exhibited in Antwerp, how could Michel-Levy have discovered the work, unrecognized, in England? Michel-Lévy did own the painting later, but where and how he obtained it must have been otherwise.

Like a Vermeer painting in which the figures are frozen in time and silence, balanced against each other in suspended narrative, Les Deux cousines hovers in a similarly delicate balance. If Watteau’s young couple is caught up in the act of offering and receiving rose blossoms—tokens of love—they act out the ritual with refinement. The standing woman, who looks neither at them nor at the horizon, presides like a sphinx.

The canvas in the Louvre represents the final stage of Watteau’s painting, but infrared examination has revealed that when Watteau began, he played with other ideas. The most interesting revelation is that he originally planned to include the figure of a standing man at the right, his head inclined. This posture could imply he was part of a couple—a gentleman inviting his lady to move on into the landscape, much as Watteau arranged the figures at the center of his fête galante Les Entretiens amoureux. But in the final painting the narrative is limited to the foreground space and the action is more constrained.

As with almost all of Watteau’s paintings, while there is general agreement that this is a mature work, there is no unanimity as to a more precise time. Adhémar would place it in 1716, but evasively added a question mark. Macchia and Montagni, Roland Michel, and Temperini followed suit. Despite this seeming unanimity, other critics would date the related drawings (and thus the painting) later. Rosenberg and Prat dated the studies for the seated woman and the man to 1717. Grasselli assigned the drawing of the standing woman to 1717, and the study of the seated woman to 1717-18. As mentioned before, Mathey alone places the painting still later, c. 1719, coinciding with the painter’s journey to London

Click here for copies of Les Deux cousines