- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

La Diseuse d’aventure

Entered July 2020; revised September 2022

Los Angeles, collection of Lionel and Ariane Sauvage

Oil on panel

27.7 x 18.3 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

La Bonne aventure

La Bohémienne

La chiromante

The Fortune Teller

Die Wahrsagerin

RELATED PRINTS

Laurens Cars after Watteau, La Diseuse d’aventure, 1727, engraving.

Watteau’s La Diseuse d’aventure was engraved by Laurens Cars in 1727. The print was announced for sale in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2677.

As Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold noted, Cars’ engraving was copied on several occasions. It was engraved in reverse by Claude Du Bosc in London, in a slightly smaller format; in an anonymous edition, also slightly smaller and with the title The Fortune Teller.

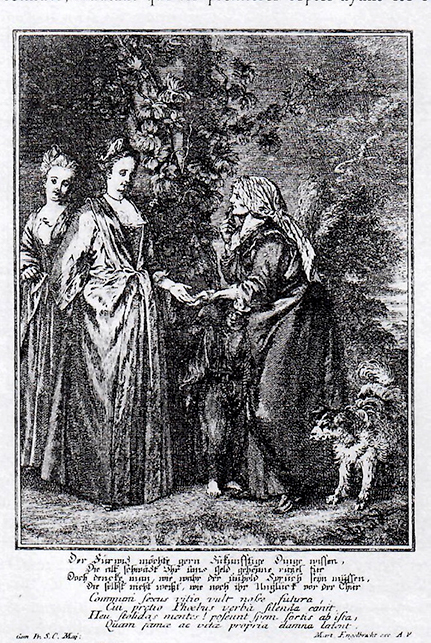

Martin Engelbrecht after Laurens Cars, La Diseuse d’aventure, engraving.

A variant of Cars’ engraving, with one less woman in attendance, figured in a German edition by Martin Engelbrecht, with the composition in reverse.

Thomas Ryley after Laurens Cars, La Diseuse d’aventure, engraving.

In England in the mid-eighteenth century, Thomas Ryley executed an engraving after Cars' print of La Diseuse d’venture. Ryley copied other images from the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé, such as La Finette.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Gilles Marie Oppenord (1672-1742; architect and designer). Oppenord’s ownership is indicated on Cars’ print: “du Cabinet de Mr Oppenort.” His ownership is confirmed by Mariette, “Notes manuscrites”: “Gravé par Laurens Cars, d’après le tableau original tiré du cabinet de M. Oppenort, architecte de Mr le duc d’Orléans.” The painting is cited in the May 7, 1742, inventory of his estate, Paris, Archives nationales, Minutier central: “no. 19: Diseuse de bonne aventure, tableau peint sur bois, copie de Wateau, «gasté en partie», bb. sc. d.,” est. 24 livres.

London, collection of Henry Farrer, FSA (1798-1866; artist and painting restorer). His sale, London, Christie’s, June 15, 1866, lot 308: “WATTEAU . . . THE FORTUNE TELLER. A charming cabinet work . . . Engraved.” According to an annotated sale catalogue at the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, the painting sold for £67.4 to Bohn. On the reverse side of the frame, hidden under layers of dark varnish and visible only with infra-red light, is the listing clipped from the 1866 sale catalogue.

Twickenham, collection of Henry George Bohn (1796-1884; publisher). His sale, London, Christie’s, March 19, 1885, lot 63: “A. Watteau. . . . THE FORTUNE TELLER / 10 in. by 7 in.” According to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the National Art Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, the painting sold for £6.6 to Philpot [as an agent on behalf of Henry Martyn Kennard].

London, collection of Henry Martyn Kennard (1833-1911; railroad magnate, Member of Parliament). By descent in his family to Henry Robert Pomeroy, 11th Viscount Harberton (b. 1958). His sale and others, New York, Christie’s, January 25, 2012, lot 110: “Attributed to Jean-Antoine Watteau, The Fortune Teller / oil on panel / 10 1/8 x 7 ¼ in. (25.7 x 18.4 cm.) / Provenance Gilles-Marie Oppenordt (1672-1742). Paris, until his death in 1742; Henry G. Bohn, 63 Lowndes Square, London, acquired in 1866 (64 gns.); (+), Christie’s London, 19 March 1885, lot 63 (6 gns.) to / Henry Martyn Kennard, London, 1885, and by descent to / Viscount Harberton and his family, until 2012 . . . “ Sold for $422,500.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 192.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 64.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 65.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 127.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 175.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), pl. 181.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 54, 277; 2: 26, 57, 61, 96, 101, 131, 144, 150, 159; 3: 19-20; IV: 30; cat. 30.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 172.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 48.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 67.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 37.

Rambaud, Documents du minutier central (1964, 1971), 2: 907.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B25.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 105a.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 116, 275.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 8.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cats. 16, 34, 88, 466.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 9.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 106, 108.

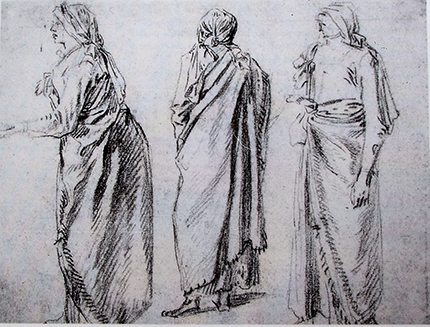

RELATED DRAWINGS

La Diseuse d’aventure has strong links to a double-sided drawing in a private collection, Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 34). The recto side is a compositional study showing a young, seated gypsy woman cradling her child and holding the open, extended hand of an elegantly dressed woman. Although they are not standing close to each other, the gypsy reads the woman’s palm. They are set off by a number of intent onlookers—four adults and two children. The scene takes place under a leafy arbor. The reverse side of the sheet shows three studies of a gypsy woman, two of the woman seen from the side and one from behind. At some point the page was trimmed on the bottom, cutting off the feet of two of the women; the trimming also cut into the compositional study, especially on the right side but also at the top and left, so that now the drawing’s lines extend beyond the edges of the sheet.

Despite the insistence of Watteau’s biographers that he never made preparatory drawings for his paintings, in certain instances he did, especially in the early part of his career. This is one of those instances. Yet this compositional drawing, despite some similarities, has little in common with the finished painting. The fortune teller in the drawing is young, seated, and holds her infant, whereas in the painting she is standing, old, and without a baby. In the drawing the woman whose fortune is being told is flanked by four adults, mostly men, and two children. There is a hint that they may be stage characters, whereas in the painting her companions are two well-dressed women. In the drawing the encounter occurs under a leafy bower whereas the painting has just an abundance of foliage growing up the side of a building. Although one would assume that the studies of the gypsy woman on the verso were made specifically for this picture, none of the three resemble the standing, hunched-over gypsy he painted, and none show her with her fingers to her mouth as she concentrates on divining the future. In short, although Watteau made these preparatory drawings for his painting, he may have made other drawings that he followed more closely or he ultimately relied more on his imagination. Either conclusion is possible.

There are no extant Watteau drawings that can be directly associated with the other figures in this painting. But a Quillard sheet of figure studies copying Watteau’s inventions in the Sauvage collection reveals that Watteau’s figures of the young woman having her palm read and her female companion were originally adjacent studies of standing women that Watteau drew from the same model. These no longer extant studies were copied by Quillard and appear at the bottom of his sheet, second and third from the left. The first of them is virtually identical to the young woman having her fortune told in the painting. Her gown is arranged the same way, somewhat open at the top and fastened at the waist. The robe-like garment has distinct borders, just as in the painting. So too her puffy hat is worn at an angle, and the disposition of her right hand is obscured as in the painting. Her left arm is less understandable in the drawing, but her hand is clearly extended forward so that her palm can be read. The woman standing next to her in the Quillard drawing—her head turned slightly to the side, one hand to her breast—is the woman behind the foremost figures in the painting. As is often the case in Watteau’s oeuvre, he exploited a drawing where two adjacent studies of the same model could be used for one painting. He was surprisingly economical in this regard.

REMARKS

While the provenance of the Sauvages’ painting is seamless from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day, its whereabouts from the time it left Oppenord’s collection in 1742 to the time it entered Farrer’s possession c. 1850 is essentially blank. Undoubtedly some of the citations in Paris and London sale between 1750 and 1850 refer to this painting, but there is no evidence to give any of them special credence.

Facing the exceptionally large number of copies of La Diseuse d’aventure and our inability to disentangle which references belong to which version, Adhémar concluded that there were two groups of copies: one in France and the other in England. However, this gross simplification ignores the various trans-Channel crossings that some of the pictures made, such as the sale of Jean-Baptiste Lebrun’s paintings in London in 1785. The Sauvages’ painting made such a crossing as well, in either the second half of the eighteenth century or the first half of the nineteenth.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, scholars thought that the version of La Diseuse d’aventure owned by Michel-Lévy (our copy 5) was the original from Watteau’s hand. Opinion shifted in favor of the picture bought by the San Francisco museum in 1968 (copy 1), but only gradually and tentatively. When Pierre Rosenberg decided to include the San Francisco painting in the 1984 Watteau tercentenary exhibition, he wrote that he was taking a chance because, “those who have seen it since its entry into the museum in 1968 have generally doubted its authenticity (with the exception of Sir Francis Watson and Claus Virch).” After the 1984 exhibition, critical opinion shifted in its favor, and this is the version that has been published by Temperini, Glorieux, and others.

Opinion swung in still another direction after the appearance, thirty years later, of yet a third contender, the painting now in the Sauvage collection. Its provenance could be traced to England throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. When it came up at auction at Christie’s New York in January 2012 it was cautiously presented as “attributed to Jean-Antoine Watteau.” In discussing the condition of the work, Wintermute stated that the panel had been truncated on three sides, the top portion of the panel had been cut away and discarded, and the right side had also been cut, sacrificing the dog and the expanse of sky visible in Cars’ engraving. However, Wintermute erred in believing that the portion of the panel with the gypsy woman and young boy was the result of an additional strip of wood having been added later and painted by another hand. Technical analysis after the sale revealed that the present panel consists of two boards, joined to the left of the fortune teller. The paint application and age, as well as wood type, are consistent from one board to the other.

The wood was examined dendrochronologically in 2013 by Professor Peter Klein of Hamburg, who concluded that the two pieces are of oak from West Germany. Oak from this region of Europe was frequently used by French artists at the time. Klein’s examination of the growth rings determined that the main section was from a tree cut down probably between 1700 and 1704, or as late as 1710. There were insufficient growth rings to date the second piece of wood.

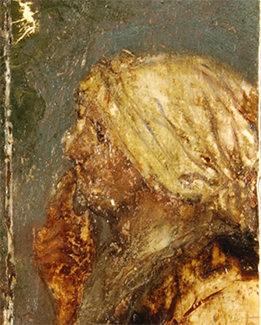

Cleaning of the panel by Michael Heidelberg of New York eliminated much of the overpaint. The jeweled aigrette in the one woman’s coiffure was removed, and the problem of the “alligatoring” of the foliage was alleviated. X-ray and infra-red examination showed pentimenti of the sort one would expect to find in an autograph Watteau.

Preliminary and final positions of the gypsy’s head as revealed during cleaning in 2012.

Preliminary and final positions of the gypsy’s hand as revealed during cleaning in 2012.

The cleaning revealed that the head of the gypsy had originally been drawn at a slightly different angle. So too, the gypsy’s hand was repositioned by Watteau during the painting process.

Changes in the woman’s bodice as revealed during cleaning in 2012 .

The cleaning revealed comparable pentimenti in the woman’s dress, particularly in her bodice and hemline.

In November 2012 arrangements were made to set the newly discovered Sauvage version next to the San Francisco version when the latter painting was on exhibition at the Grand Palais. Included in the unofficial jury were Pierre Rosenberg, Marie-Catherine Sahut, Christopher Vogtherr, Martin Eidelberg, and others. The consensus favored the Sauvage version as autograph.

Regardless of which version of the composition was being considered, critics have agreed that La Diseuse d’aventure represents a relatively early work in Watteau’s career. Mathey, Macchia and Montagni, as well as Temperini, assigned the painting to c. 1709, which, by today’s standards, is perhaps too early by a few years. Rosenberg dated the related drawings and thus the painting to c. 1710. Glorieux decided on 1711, while Adhémar and Roland Michel preferred c. 1711-12. Francis Watson favored a date not later than 1712.

Watteau, La Diseuse d’aventure (detail).

Watteau, L’Alte (detail). Madrid, Museo del Prado, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Rather than trying to pinpoint the year in which it was painted, it is perhaps more useful to note the remarkable parallel between the figures of the women at the left side of La Diseuse d’aventure and at the left side of L’Alte, one of Watteau’s early depictions of a military encampment. In both pictures a woman in a bright yellow gown stands with her back to us so that essentially all we see is the gown. In both the sleeve ends in a broad border of blue and an echo of that blue at the neckline. Although the figures may be artistic sisters, there are differences, especially the way that the woman in La Diseuse raises her skirt with her left hand, revealing a glimpse of the orange underskirt. In both works this woman faces a second woman, and the faces of these second characters are structured in remarkably similar manners. Like La Diseuse d’aventure, L’Alte is generally dated to the years shortly after 1710.

The Flemish aspect of Watteau’s subject matter reinforces the idea that La diseuse d’aventure was executed in the early part of his career, at a time when he emulated Northern models overtly. A Teniers painting in the Tronchin collection, Paris, recorded several decades after Watteau executed his composition, suggests the type of model he might have seen and emulated in Paris. His model might not have been by Teniers or his workshop; it could well have been by a lesser artist. For example, a drawing of a gypsy fortune teller by Pieter Jansz. Quast depicts a scene whose iconographical elements and overall composition presage Watteau’s composition to a remarkable degree. The important thing is that the principal motifs –the aged and bent gypsy, the children, the dogs—were standard tropes in such scenes—including Watteau’s. That Watteau turned the scene into an elegant, courtly vision is just what we would have expected.

Click here for copies of La Diseuse d’aventure