- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

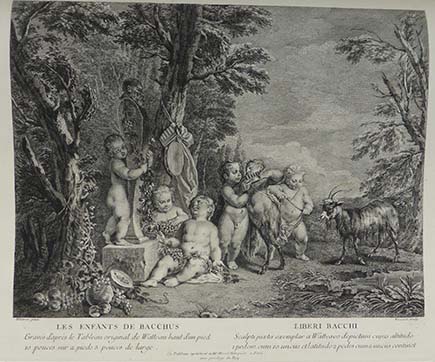

Les Enfants de Bacchus

Entered November 2021; revised December 2021

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. RF 1950 20

Oil on canvas

60 x 74 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Amours

RELATED PRINTS

Étienne Fessard after Watteau, Les Enfants de Bacchus, 1734, engraving.

Les Enfants de Bacchus was engraved in reverse by Étienne Fessard. The print was announced for sale in the April 1734 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 753.

PROVENANCE

Paris and Lyon, collection of François Morel (1680-1763; banker; conseilleur secretaire du Roi). Morel’s ownership is noted on the Fessard engraving. Descended in the Morel family.

Lyon, collection of M. Morel de Voleine (descendant of François Morel), c. 1892 (reported by Paul Mantz).

Cogny (Rhône), collection of M. Morel de Voleine, c. 1921 (reported by Dacier, Vuaflart , and Hérold).

Paris, collection Grau; sold Paris, Hôtel Drouot, December 16, 1929, lot 60: “WATTEAU (Jean-Antoine) . . . Les Enfants de Bacchus. Un groupe des trois amours, dont deux sont assis et le troisième debout sur un piédestal de Dieu Pan, de qu’il entourede ses bras. A un arbre sont accrochés une draperie rose, une syrinx et un tambourin. Plus loin, à gauche, autre groupe formé d’un petit faune jouant de la flûte et de deux autres amours, l’un deux conduisant une chèvre. A terre des pampres, des raisins, grenades et autres fruits. Peinture sur toile. Haut., Cadre ancien.” Sold for 66,000 francs to Binet on behalf of M. and Mme. J. M. Gros.

Paris, collection Madame Alice Célestine Gros; bequeathed to the Musée du Louvre in 1950.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 117.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 119.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 37.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 180-81.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 2: 38, 46, 63, 96, 122, 131, 162, 3: cat. 221.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 17.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 114.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 66.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 74.

Paris, Louvre, Catalogue illustré (1972), 399.

Paris, Louvre, Catalogue illustré (1974), cat. 929.

Compin and Roquebert, Catalogue sommaire (1986), 5: 100.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B 93.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 89.

Boerlin-Brodbeck, “La Figure assise” (1987), 165.

Lallement, “Inventaire des tableaux à sujets musicaux" (1997), 215.

RELATED DRAWINGS

No Watteau drawings have been associated with Les Enfants de Bacchus.

REMARKS

The principal issue concerning this composition is whether the painting now in the collection of the Louvre is actually the painting from the Morel collection that was engraved in 1727. It was lost sight of in the later eighteenth century after Morel returned to Lyon, and was not rediscovered until the last years of the nineteenth century. Edmond de Goncourt, for example, did not know of it. It returned to the public sphere only after M. Morel de Voleine of Lyon contacted Paul Mantz, and reported that he possessed the two Watteau paintings that his ancestor owned: Les Fêtes au dieu Pan and Les Enfants de Bacchus. Although grateful for the information, Mantz does not seem to have gone to see and verify the attribution. Similarly, Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold appear to have contacted the subsequent owner but they did not actually see the painting or opine on it. Similarly Réau listed the painting in his catalogue but there is no evidence that he saw it. The situation changed when the painting entered the Louvre in 1950. Adhémar, then a curator there, wrote that Watteau’s original painting was lost and that the Louvre picture was only a replica with some modifications—in the trees at the left, and the height differed (although the height of the Louvre painting and the Fessard engraving correspond exactly). Modern scholars have apparently not accepted the Louvre painting. Ferré and Roland Michel continued to describe the original as lost and, similarly, Temperini and Glorieux did not mention the Louvre painting—implying that they too did not accept it.

The painting’s provenance in the Morel family from its earliest years to the first decades of the twentieth century is of great significance, even more so because through all those years it stayed with a second Watteau painting, Les Fêtes au dieu Pan. Both works have suffered greatly. The surface of Les Enfants de Bacchus shows substantial paint losses and in some instances disfiguring overpainting that leaves the putti as mere blurs of color. Their contours and facial features have been exaggerated. But even in those areas with obvious overpainting, there is also a convincing hint of quality beneath.

The picture may have suffered, but its rich, painterly approach is outstanding. It far outshines what we see in the paintings of putti after Rubens that are attributed to Watteau. The children in the Louvre painting are robust, exuding both charm and vitality. They suggest what Watteau’s other paintings of putti with classicizing subjects—such as Les Enfants de Sylene and L’Amour mal accompagné—would look like if the canvases had survived.

As mentioned, Morel owned two Watteau paintings—Les Enfants de Bacchus and Les Fêtes au dieu Pan—but they were not pendants. The former is horizontal, the latter vertical. Also the scale of the figures is quite different, Les Enfants de Bacchus having large figures in relation to the overall composition, while Les Fêtes au dieu Pan has small figures in a vast landscape. The one element that binds them is that both reference the gods of classical Antiquity, but even here they reflect different approaches. Les Fêtes au dieu Pan with its unusual mixture of satyrs and commedia dell’arte characters, is indebted to Watteau’s teacher Claude Gillot. On the other hand, the imagery of Les Enfants de Bacchus is related to Antique reliefs and French Baroque sculptors such as Jacques Sarazin.