- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

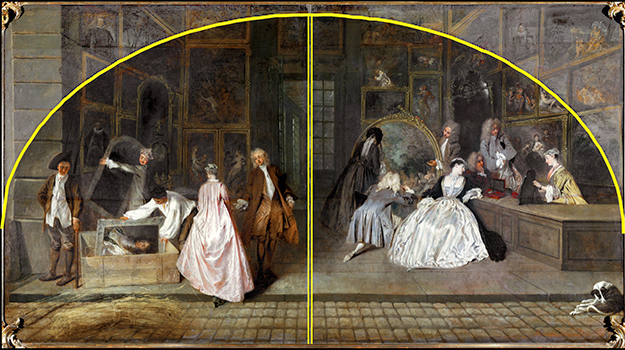

L’Enseigne de Gersaint

Entered November 2020; revised July 2021

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Berlin, inv. GK I 1200/1201

Oil on canvas

166 x 306 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Das Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint

Gersaint’s Shopsign

Das Geschäftsbild des Kunsthandlers Gersaint

L’insegna di Gersaint

Das Ladenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint

The Shopsign

RELATED PRINTS

Pierre Aveline after Pater’s copy of Watteau’s L’Enseigne de Gersaint, 1732, engraving.

This composition was engraved in 1732 by Pierre Aveline. It was announced for sale in the March 1732 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 550, and in the July 1732 issue, p. 1609. However, it was produced under unusual circumstances. When Watteau’s signboard was taken down, its lunette shape was modified and made rectangular by unfolding the upper portions. Pater was instructed or commissioned to paint a replica of the now-rectangular picture, reduced in scale to only one third the size of Watteau’s original (our copy 1). Aveline’s engraving was based on Pater’s reduced copy, and it duplicated the scale and proportions of Pater’s copy.

PROVENANCE

Paris, with Edme François Gersaint (1694-1750; dealer in paintings and luxury goods).

Paris, collection of Claude Glucq (c. 1674-1742; member of parliament). Glucq’s ownership is cited in the announcement of the Aveline engraving in the November 1732 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2450: ”Elle fut vendue à M. Glucq.”

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). Jullienne’s ownership is cited in the announcement of the Aveline engraving in the November 1732 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2450: ”On la voit à présent dans le Cabinet de M. de Jullienne.”

Amsterdam, c. 1746, with Pieter Boetgens (art dealer); sold to King Frederick the Great of Prussia (Friedrich II).

EXHIBITIONS

Berlin, Königliche Akademie, Gemälde älterer Meister im berliner Privatsbesitz (1883), cat. 2a, b (as Watteau, Das Geschäftsbild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Berlin, Königliche Akademie, Exposition d’oeuvres de l’art français (1910), cat. 67, 89 (as Watteau, Das Geschäftsbild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).Berlin, Meisterwerke aus den Preussischen Schlössern (1930), cat. 189 (as Watteau, Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Paris, Palais national, Chefs-d’oeuvre (1937), cat. 237 (as Watteau, L’Enseigne de Gersaint).

Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, Malerei des 18. Jahrhunderts (1947), cat. 113 (as Watteau, Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, Französische Kunst (1951), cat. 55 (as Watteau, Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Paris, Petit Palais, Chefs-d’oeuvre de Berlin (1951), no. 59 (as Watteau, L’Enseigne de Gersaint).

Berlin, Museum Dahlem, Meisterwerke aus den Berliner Museen (1951), 39, cat. 136 (as Watteau, Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Munich, Residenz, Europäisches Rokoko (1958), cat. 222 (as Watteau, Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Meisterwerke (1962), cat. 99 (as Watteau, Firmenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint).

Paris, Louvre, Première exposition des plus beaux dessins du Louvre (1962), cat. 99.

Paris, Louvre, Peinture française (1963), cat. 39 (as Watteau, L’Enseigne de Gersaint).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 73 (as Watteau, The Shopsign, Gersaint’s Shopsign).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nicolai, Description des villes de Berlin et de Potsdam (1769), 481.

Osterreich, Description (1773), nos. 561-62.

Rumpf, Königlichen Schlösser in Berlin (1794), 262.

Hécart, Biographie valenciennoise (1826), 11.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 124.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 126.

Mantz, “L’Ecole française” (1859), 272.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 95.

Dohme, "Zur Literatur über Antoine Watteau" (1876), 89-90, cat. 2, 3.

Dussieux, Artistes français à l’étranger (1876), 222.

Dohme, Kunst und Künstler (1880), 22.

Dohme, “Die Französische Schule des XVIII. Jahrhunderts” (1883), 107-08.

Michel, “Frédéric II et les arts” (1883), 908, 915.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 51-52.

Ephrussi, “Exposition d'oeuvres de maîtres anciens” (1884), 102-03.

Fournier, Histoire des enseignes (1884), 196-97, 406-08.

Eudel, L'Hôtel Drouot et la curiosité (1886), 103.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 127, 145, 185.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 48, 80-82.

Rosenberg, Watteau (1896), 90, 93.

Dilke, French Painters (1899), 95.

Laban, “Bemerkungen zum Hauptbilde Watteaus” (1900), 55-59.

Seidel, Collections d’oeuvres d’art françaises (1900), 25, cat. 158-59.

Fourcaud, “L’Existence de Watteau” (1901), 167-71.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 135.

Josz, Watteau (1904), 197-98.

Vauxcelles, “L’Enseigne de Gersaint” (1909), 200-18, 307-08.

Alfassa, “L'Enseigne de Gersaint” (1910), 126-72.

Alvin-Beaumont, Watteau en Allemagne (1910)

Seidel, “Das Firmenschild des Gersaint” (1910), 174-86.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), no. 108.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), 130-38.

Maurel, L'Enseigne de Gersaint (1913).

Alfassa, “A Propos d'un livre récent” (1913), 349-81.

Alfassa, “Response de M. Paul Alfassa” (1914), 61.

Maurel, “A propos de «l’Enseigne de Gersaint»” (1914), 54-60.

Maurel, “A propos d'un livre récent" (1914), 54-64.

Lebel, “À Propos de deux esquisses” (1921), 55-61.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), I: 108-112; III: cat. 115.

Gillet, Watteau (1921), 184-86.

Hildebrandt, Antoine Watteau (1922), 65-66.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 182.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 15-16, 49.

Réau, “Le premier état de ‘L’Enseigne de Gersaint’” (1931), 58-61.

Réau, “À Propos de ‘L’Enseigne de Gersaint” (1931), 59-62.

Dacier, La Gravure de genre (1932), 59.

Fischel, “Altes und Neues vom Schild des Gersaint” (1932), 341-53.

Vallée (Adhémar), “Sources de l’art” (1939), 69.

Brinckmann, Watteau (1943), 75-80.

Kunstler, Watteau l'Enseigne de Gersaint (1943).

Aragon, L'Enseigne de Gersaint (1946).

Florisoone, Le Dix-huitième siècle (1948), 34-35.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 215.

Tolnay, ”L’Embarquement pour Cythère” (1955), 102 n. 14.

Van Heule, “L'Enseigne de Gersaint“ (1955).

Parker and Mathey,Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1957), cat. 140, 180, 366, 688, 787.

Rave, Das Ladenschild des Kunsthändlers Gersaint (1957).

Boucher, “Les Sources d’inspiration de l’enseigne de Gersaint” (1957), 123-29.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 32, 59, 69.

Adhémar, “L'Enseigne de Gersaint” (1964), 6-16.

Levey, “The Pose of Pigalle's 'Mercury'” (1964), 462.

Levey, Rococo to Revolution (1966), 80-83.

Brookner, Watteau (1967), pl. 44.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 212.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 3: cat. A 39

Boerlin-Brodbeck, Watteau und das Theater (1973), 200-02.

Banks, Watteau and the North (1977), 231-91.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1977), 232-53.

Le Coat, “Modern Enchantment” (1978), 169-72.

Meyer, La Vie quotidienne en France (1979), 270-74.

Posner, “Watteau’s Shopsign” (1979), 29-33.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 248.

Neuman, “Watteau’s L’enseigne de Gersaint” (1984), 153-64.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 123-24, 148, 201, 266, 271-77.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 46, 51, 70-71, 109-11, 116-17, 210, 221, 265-66, 272, 302.

Wine, "Watteau's Consumption and L'Enseigne de Gersaint" (1990), 163-70.

Vidal, Watteau’s Painted Conversations (1992), 165-96.

Licht, “Gersaint’s Shop Sign” (1994), 36-38.

McClellan. “Watteau's Dealer” (1996), 439-53.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 24, 38, 87, 98, 160, 203, 354, 422, 444, 627, 659, 661.

Craske, Art in Europe, 1700-1830 (1997), 172-75.

Caplan, In the King's Wake (1999), 75-97.

Glorieux, À l'Enseigne de Gersaint (2002), 72-89.

McClellan, “The World of Art Dealing” (2006), 150-52.

Vogtherr and De Calisse, “Watteau’s ‘Shopsign’” (2007), 296-304.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. 7.

Raux, “Virtual Explorations” (2018).

RELATED DRAWINGS

Few extant drawings can be linked directly with L’Enseigne de Gersaint. Some are older studies that the artist seems to have turned back to, while others were apparently drawn specifically for the new painting. Although Watteau was ill and his offer to paint the signboard was made spontaneously, he remained true to his normal studio practice.

A red chalk drawing of a standing woman seen from behind (Rosenberg and Prat 203) was used for the woman at the back in the right-hand section of the signboard. She seems to be attentively examining the large oval painting of bathing maidens, and it has been thought that she holds a lorgnette, but others have suggested it is a closed fan.

The date of the drawing is problematic. Because of its employment for L’Enseigne, Grasselli dated it close in time to the painting. On the other hand, Rosenberg and Prat have argued that the drawing is much earlier. For them, the reliance on just red chalk allies this study with the artist’s early drawings, but they allow that the strong accents of red chalk at the lower edges of the skirt are indicative of a slightly later date, c. 1713-14. A date closer to L’Enseigne seems more reasonable, both stylistically and logically.

The two workmen in the left-hand portion of the painting derive from a boldly drawn study now in the Musée Cognac-Jay (Rosenberg and Prat 661). The man at the left of the drawing, packing a portrait of a bewigged man into a crate, is drawn largely in black chalk, while the other man, lifting a cumbersome mirror or painting, is drawn principally in red chalk. The second man is drawn more spontaneously, so much so that one may wonder whether the figure was drawn from memory or from a posed model. Unquestionably, the Cognac-Jay drawing was made specifically for the painting, but did Watteau have access to live models while staying with Gersaint? This is an intriguing question. Some have noted that an early Watteau drawing with studies of a man lifting an object or a person (Rosenberg and Prat 98) also bears some resemblance to the workmen in L’Enseigne, but this may be merely fortuitous.

A sheet with four studies of a woman’s head in the Stockholm Nationalmuseum (Rosenberg and Prat 659) is generally believed to depict Anne Elisabeth Sirois or her younger sister, Marie Louise Sirois who was Gersaint’s wife. Moreover, it is generally agreed that this is the same woman who appears at the right of L’Enseigne, behind the counter of Gersaint’s shop. None of the four studies on the Stockholm sheet match the woman in Watteau’s painting. While the head at the lower left is the closest (except that it is in reverse), the drawing shows the face in slightly more than profile, whereas the woman in the painting is cast in strict profile. There are other studies of this woman (e.g., Rosenberg and Prat 521, 627), and Watteau may well have turned to another drawing in this series, one that has not survived.

A number of additional drawings have been associated with L’Enseigne but not convincingly. A study of a standing man (Rosenberg and Prat 160) has been linked with the man in a brown suit in the left half of the signboard. There he extends his right hand to the woman entering the shop while his other hand is tucked in his pocket. In the drawing he extends his right arm, but at a much higher level and farther out from his body. The legs of the two men are similarly positioned, except that those of the man in the painting are closer to each other and almost touch at the knees. Still greater differences are registered in the carriage of the two men. In the drawing he stands upright while in the painting he arches his body into a fluent curve. Ultimately, although there are analogies, the differences far outweigh them.

REMARKS

The circumstances surrounding the creation of this signboard are well documented in Gersaint’s Life of Watteau. There he states that when Watteau returned from London (which occurred by August 1720), the ailing artist turned to him, hoping to find a place to stay.

On his return to Paris, which was in 1721 [sic], during the first years of my establishment, he came to me to ask if I would agree to receive him, and allow him to stretch his fingers, those were his words, if I were willing, as I was saying, to allow him to paint a plafond that I was to exhibit outdoors. I had some reluctance to grant his wish, much preferring to occupy him with something more substantial; but seeing that would please him, I agreed.

Watteau’s offer to paint a signboard was based, at least in part, on his previous experience in executing such works.

Watteau, A Barber’s Shop, red chalk, 12.2 x 23.4 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

Two well-known drawings from the early part of Watteau’s career offer evidence of his activity as a sign painter. The more elaborate design is a scene of a barber shop (Rosenberg and Prat 24). At the center a man is being shaved, while at the right a man is offered a periwig; at the left a servant brushes out a periwig while a gentleman examines himself in a mirror. This drawing is not simply a study from life, nor is it a theatrical scene as Roland Michel has argued. In atypical fashion, Watteau has composed seven figures in obvious symmetry. The man being shaved is seated directly at the center, and the subsidiary activities are set at the sides, the one balancing the other. Equally important, the symmetry is enhanced by pedestals and drapery that firmly terminate both sides. The symmetry of these elements would have been even more apparent had the drawing not been cropped slightly at the right, thus leaving only a portion of the pedestal and drapery. Although the poses are varied, the formal nature of Watteau’s composition calls attention to itself.

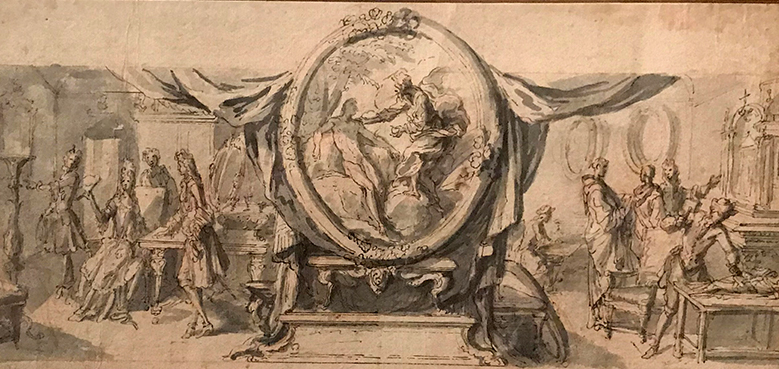

Antoine Dieu, Design for a Sign or Trade Card for a Sculptor’s Studio, ink and wash drawing, c. 1690-1710. Paris, Musée des arts décoratifs.

In many ways Watteau’s work recalls a contemporary drawing by Antoine Dieu for a sculptor’s studio. Dieu also relied on an emphatic symmetry to structure his design: divided into two bilateral scenes, a sculptor works at the right and another meets with a female client at the left. Dieu’s central medallion features God Creating Adam from Clay and, like Watteau’s man being shaved, its axial placement emphasizes the profession of the sculptor. Not least of all, Dieu framed this central medallion with symmetrical folds of drapery, just as Watteau used swags of drapery at each side to emphasize the symmetry of his design.

Watteau, A Draper’s Shop, red chalk, 12.2 x 33.4 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

Watteau’s second drawing (Rosenberg and Prat 87) shows the interior of a draper’s shop. It too throws light on the signboards that he painted in his early career and, equally important, many of its elements anticipate L’Enseigne de Gersaint. At the right, a gentleman steps from the street into the shop, seemingly engaged in conversation with a salesman holding a bolt of cloth. Beyond them, a young man leans against the counter and speaks with a saleswoman. Remarkably similar characters populate L’Enseigne. Finally, the masonry at the right and the play between the cobblestone street and the interior space of the shop anticipate key elements in L’Enseigne. The drawing’s marked asymmetry calls for a corresponding scene at the left: if there once was one, the analogy with L’Enseigne would be still more apparent.

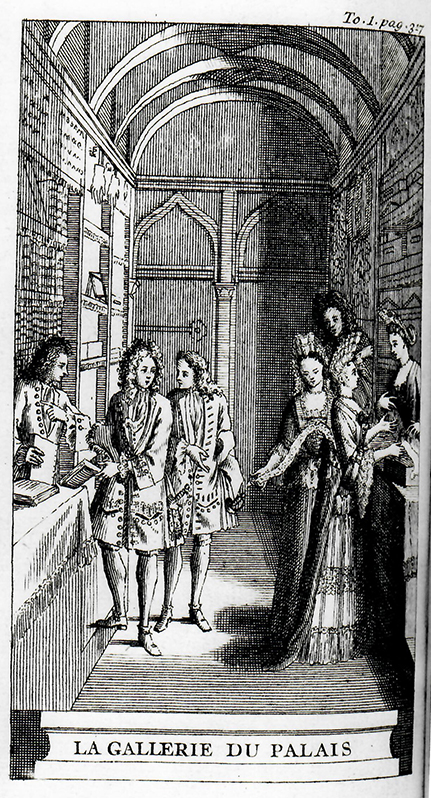

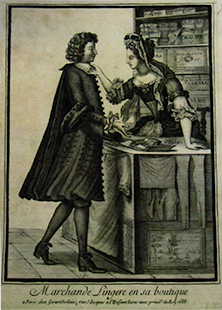

By sheer coincidence, one of the frontispieces that Watteau prepared for the 1714 publication of the plays of Thomas Corneille shows the interior of a shop in the Palais Royale. Watteau’s design derives directly from a Dutch engraving of c. 1700, but the more important point is that his picture show his awareness of the conventions for depicting store interiors. Also germane are the genre scenes set inside shops found in popular prints. The many images of saleswomen behind their counters, selling the store’s wares and often flirting with the customers, is another part of the rich visual repertoire that Watteau undoubtedly knew. Whether by Bernard Picart, Claude Simpol, Robert Bonnart, or the many anonymous minor masters that worked in this trade, these prints helped prepare the way for L’Enseigne.

Anonymous French artist, A Draper’s Shop, oil on canvas, each 41 x 50 cm. Whereabouts unknown.

Also worthy of attention are signboards by other artists, especially Parisian ones, that Watteau may have seen. Unfortunately, little of early eighteenth-century Parisian genre painting is extant, and signboards were particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time and use. Although few examples of such work have survived, they offer parallels with the Watteau drawings in the Louvre and forecast key features in L’Enseigne. Pendant paintings showing a draper’s shop which François Boucher published in the 1950s, and which I considered a decade later, are of prime importance. Their recent auction (Paris, Hôtel Drouot, January 11, 2019, lot 13) lets us reconsider their pertinence. When Boucher published the two pictures, he presented them as anonymous French works of c. 1700, and the question of attribution still stands today. In certain ways the figures recall the animated staffage in paintings such as Pierre Denis Martin’s View of the Quai de la Rapée in the Musée Carnavalet, painted around 1700. Certainly these paintings originated in the same period. The dramatically high lace fontanges worn by the two women establish that the paintings were executed in the last decade of the seventeenth century or the first decade of the eighteenth; that is, they were made before or at the same time as Watteau’s drawings for signboards.

The shop setting of this bipartite signboard anticipates the solution Watteau employed for L’Enseigne, namely a view from the street into a gallery, with masonry at one side representing the exterior wall of the building. At the right, attention is focused on a vendeuse behind the counter, showing wares to her clients, paralleling the right half of L’Enseigne. Similarly, the left-hand canvas includes workmen filling crates; this motif strikingly parallels Watteau’s scene of workmen packing away the old portrait of Louis XIV that had previously served as the sign for Gersaint’s shop, called “Au Grand monarque.” The imagery of this anonymous signboard is remarkably close to the narrative that Watteau painted just a few years later. Indeed, the parallels between the two works are so striking that one might be tempted to claim that the one inspired the other. That probably was not the case, but the evident continuum for such genre scenes on signboards should encourage future scholars to investigate the field of signboards further.

Anonymous French engraver, View of the Pont Notre-Dame Decorated to Celebrate the King’s Recovery in 1687 (detail), engraving.

Once installed on the exterior of Gersaint’s shop, Watteau’s signboard aroused great curiosity and excitement. It hung there at 35 Pont Notre-Dame. The enormous scale and lunette shape of Watteau’s sign corresponded to the demands of the architectural setting—under a depressed arch, above the central doorway. All the shops on the Pont Nôtre-Dame had uniform facades, but once Watteau’s signboard was in place, Gersaint’s establishment stood out. As the dealer wrote, “One knows the success this work had . . . it attracted the looks of passersby; and even the most skilled painters came several times to admire it.”

The original lunette shape of L’Enseigne de Gersaint, with the later modifications indicated in halftone.

The signboard’s success was so great that after a few weeks Gersaint felt compelled to take it down and install it in his gallery as a work of art. At that time the picture was radically modified. The canvas, which had been folded back to create a lunette, was unfolded to restore its original rectangular shape. These new areas were painted with framed pictures to match those depicted on the gallery walls below. It is generally thought that these modifications were executed by Watteau’s assistant, Jean-Baptiste Pater. As has been mentioned, Pater then made a much smaller copy of the now-rectangular painting (our copy 1 below), and Pater’s copy was engraved by Aveline to represent L’Enseigne in the Jullienne corpus.

Jean-Baptiste Pater after Watteau, L’Enseigne de Gersaint, oil on canvas, 50 x 82 cm. Geneva private collection.

In both Pater’s copy and Aveline’s engraving, the store is presented as a single, unified composition, with the perspective converging at the open door on the central axis. Most scholars, including those involved in the recent technical analysis of the paintings in Berlin, have presumed that the work was cut into two halves after it left Paris, probably in 1746 when it was with the Amsterdam art dealer Pieter Boetgens. Vogtherr contends that, “The exact analysis of the fabric edges of the two parts and the absence of tension garlands” prove that it was cut in two after it was executed.

However, as Adhémar proposed in 1964 when the painting was examined in the Louvre laboratory, and as was reiterated by Posner in 1979, and as I argued elsewhere in 2020, there is much evidence that Watteau conceived and executed the signboard as a two-piece work from the start. Had it been painted in one piece, i.e., on one continuous canvas—which is what Vogtherr and the Berlin conservators maintain—the work would have reached a considerable, ungainly size. As others have noted, the canvas would certainly have been difficult to handle in Gersaint’s small quarters. His shop measured only 3.56 meters in width, and 3.4 meters in depth. If the sign were made from one enormous canvas, matching the lunette-shaped space over the doorway, it would have filled Gersaint’s store. Maneuvering a canvas of such unwieldly proportions, approximately 3.5 meters or more, in the restricted space of Gersaint’s interior would have been difficult. Two canvases of equal width, measuring only 1.75 meters each, would have been far more convenient for the ailing Watteau to handle.

Two-part signboards were an established format for the genre, as seen in the anonymous work for a draper’s shop published by Boucher. Moreover, Watteau’s design for L’Enseigne is itself quite telling. It reveals that the picture was meant to be in two separate sections from the start. Both the left- and right-hand sections present semicircles of figures, each complete and self-absorbed. In the right half, the figures at the counter focus their attention on a mirror, while a couple at the back examine a large oval painting of female bathers. All the figures in this right-hand section turn their backs and their attention away from the people in the left-hand side. Likewise, the people in the left-hand section are grouped around the old sign being packed away, and no one is aware of what is transpiring as the right side. As slight as his illustration for La Gallerie du palais is, Watteau took care to show one man at the left looking across to the figures at the right, providing psychological interest and binding the two parts of the composition together. The characters’ postures in L’Enseigne emphasize the semicircular nature of their groupings. For example, in the left-hand portion, both the woman climbing the curb and the man helping her form an exaggerated curve, leaning toward the left side of the composition, and away from all that lies opposite. The figures in the right half are all inclined to the right. It is as though each group had an aversion to the other. Their gestures and poses emphasize the fact that from its inception the signboard was intended to be bipartite. The central axis, the boundary between the two halves, intercepts no person or object of consequence. From the start, this central section was designed to be a neutral space, perhaps to provide room for whatever structural or framing elements were needed to support the signboard.

Anonymous French artist after Watteau, partial copy after L’Enseigne de Gersaint, oil on canvas, 98 x 130 cm. Geneva, private collection.

Additional evidence that L’Enseigne was in two parts when it was still in Paris is offered by two copies executed there in the first half of the eighteenth century. These two high-quality copies of the signboard, evidently painted in the French capital, record the two sides on two separate canvases. The copy of the left-hand portion of L’Enseigne was described in a 1769 Paris sale, and in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it was in the Michel-Levy collection (our copy 2). A century ago it was deemed of such quality that many thought it was the original; some maintained, perhaps with good reason, that it was executed by Pater. Moreover, there also was a copy of just the right-hand side of Watteau’s L’Enseigne in Paris (our copy 3). This picture was recorded there in an auction in 1829 but has not been seen since. Presumably the pendant to the painting later in the Michel-Levy collection, these two copies help establish that Watteau’s painting was in two parts before it left the French capital.

Much has been made of the fact that L’Enseigne was referred to as “en plafond” when it was engraved for the Jullienne corpus. When Aveline’s engraving was announced in the July 1732 issue of Le Mercure de France, it was written: “gravée d’après la fameuse Enseigne que Watteau peignit en plafond pour M. Gersaint.” Some have taken this to mean that the sign projected out at an angle, creating a canopy or ceiling. Instead, it may simply have referred to the sign being hung high above the viewer. “Plafond” seems to have been an expression employed for a signboard displayed at a height. When Charles Nicolas Cochin (1715-1790) described the signboard that the young Chardin painted for a surgeon, he recounted how the surgeon awoke the day after it was installed, and saw people stopping in front of his establishment to look at “ce plafond.”

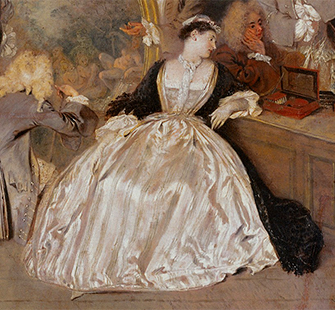

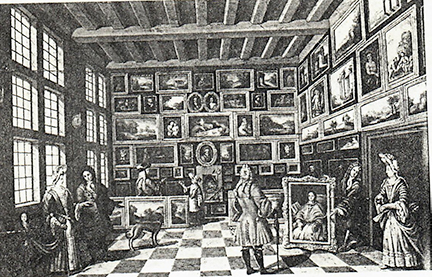

Watteau’s signboard, so strikingly beautiful, is a seemingly effortless portrayal of life among wealthy members of Parisian society considering works of art to adorn their homes and assert their status. The woman seated at the counter contemplates luxury goods, lacquered objets de toilette; and slightly to her left a mirror and elaborate table clock emphasize the richness of Gersaint’s commerce. As fresh and spontaneous as Watteau’s painting is, it also is bound to pictorial conventions. Of great importance are the many paintings of picture galleries painted primarily by Northern artists in the seventeenth century.

One easily thinks of early seventeenth-century scenes by David Teniers and other masters, where the riches of these collections are portrayed with precision. These pictorial inventories still serve modern viewers who hope to reconstruct collections that have long since been dispersed.

Anonymous Dutch(?) artist, At A Painting Dealer’s Shop, oil on panel, 40.5 x 62 cm. Whereabouts unknown.

Moreover, such scenes were not confined to the early seventeenth century. They were still a part of European pictorial themes in Watteau’s time, as can be seen in a painting as evidenced by the fashions depicted—especially the fontanges worn by the women—that dates from c. 1690-1715, in other words, shortly prior to L’Enseigne.

Watteau would have been cognizant of this tradition of gallery scenes. While he gave primacy to the figures in the foreground, and executed the pictures hanging on Gersaint’s walls freely, with a charged brush and less than normal detail, many of the compositions can be identified, at least in a generic way—as Venetian school, Flemish school, etc. Surprisingly few pictures in Gersaint’s gallery prove to be identifiable with specific works. This field of inquiry was initiated by Fischel, but is yet to be explored fully.

A good example of the dilemma of separating generic from specific references is the picture on the wall at the right, behind the woman showing the mirror. Its subject is the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine, and its composition and style recall the many paintings on this theme by Veronese, such as one then in the Crozat collection and now in the Hermitage. But thus far it has not proven possible to associate the picture in L’Enseigne with any specific version by the Venetian master. Although Watteau is known to have copied other Veronese paintings with this theme, even a drawing after two of them often cited in relation to L’Enseigne (Rosenberg and Prat 422), none correspond to the picture depicted on the wall of Gersaint’s gallery.

A number of the other paintings shown in Gersaint’s gallery correspond more to types than specific models. Above the St. Catherine is a Procession of Bacchus that resembles many paintings with this subject executed by Rubens, Van Dyck, and Jordaens. In the left-hand section of L’Enseigne is a large Pan and Syrinx that suggests Rubens and his Northern compatriots, but we are unable to pinpoint Watteau’s source.

Paintings in the upper reaches of L’Enseigne reveal a more deliberate program of borrowing. It should be remembered, these are areas where Pater may have been painting. As Michael Levey has pointed out, the painting in the upper right corner of the canvas faithfully copies a composition by Jacob Jordaens, although the Flemish master’s composition has been extended to create a more horizontal format.

Likewise, a picture at the very top of the wall in the right-hand section of L’Enseigne shows a woman milking a cow and a young goatherder with his animals. This farmyard scene is closely based on a Titian composition which is known through a drawing as well as a woodcut by Giovanni Britto.

Banks has suggested that the uppermost left picture on the wall in the left-hand section of L’Enseigne is Rubens’ Portrait of King Philip IV. The resemblance is strong, although there are many similar portraits with this format.

For critics such as Le Coat and Banks, the paintings depicted in Gersaint’s store can be read in allegorical terms. For Le Coat, the collection is an allegory of life, while for Banks it is an allegory that both summarizes Watteau’s artistic evolution and presents a Vanitas warning. Such interpretations are highly subjective and rest on investing meanings in clocks, mirrors, straw packing—all materials one would naturally find in a shop like Gersaint’s. It seems unlikely that Watteau would have expected passersby to stop, look at the sign high overhead, and locate and decipher such hidden meanings. Rather, it seems more reasonable that the sign describes in a straightforward way the commercial aspects of Gersaint’s establishment—the selling and buying of paintings and expensive objets d’art. Like all such signs, it simply advertised the business conducted within the store.

By the same token, scholars have sought to trace some of the principal elements of the composition to sources in Rubens’s paintings. The dog licking itself was based upon the one in the left foreground of The Coronation of Marie de’ Medici, but in the reverse direction. Probably Watteau made a drawing of Rubens’s dog, but relied on a counterproof for this painting. Interestingly,Rubens situated the dog in the right foreground of his picture, and Watteau did the same in L’Enseigne.

On the other hand, the often-cited comparison between the woman seated at the counter in L’Enseigne and the figure of Marie de’ Medici in the Birth of Louis XIII is less convincing. Both women are seated and their torsos and head are inclined to their left, but Rubens chose a more complex positioning of the body. The upward turn of the queen’s head to her left is counterbalanced by her right shoulder turning downward; similarly her legs are dramatically turned to one side while her torso turns in the opposite direction. Her complicated contrapposto makes her a worthy descendant of Michelangelo’s sibyls on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In contrast, Watteau’s woman sits in quiet, languorous repose, resting her weight on her elbow as she turns to look at the toilette set being proffered.

Click here for copies of L’Enseigne de Gersaint