- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

L’Escarpolette

Entered February 2022

Helsinki, Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, inv. A II 1413

Oil on canvas

95 × 73 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

The Swing

RELATED PRINTS

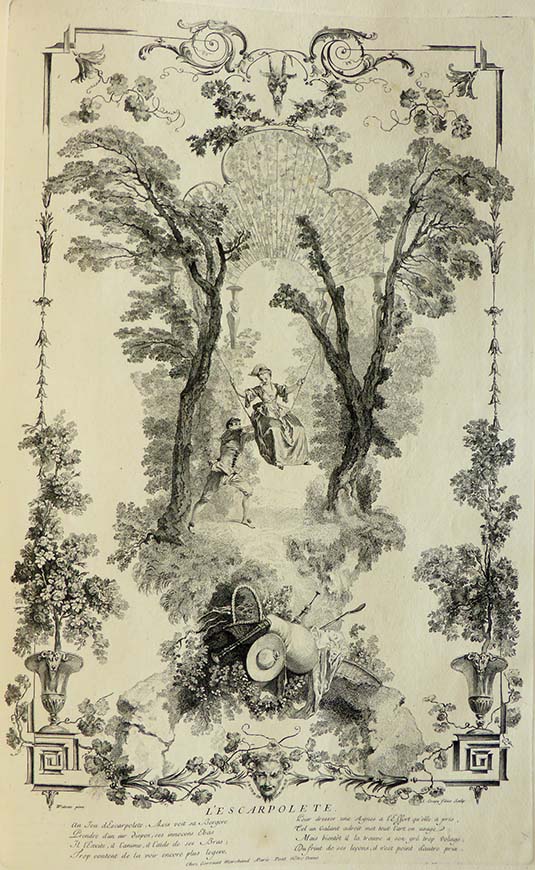

Louis Crépy fils after Watteau, L’Escarpolette, engraving, 1728.

Watteau’s arabesque L’Escarpolette (spelled “L’Escarpolete”) was engraved by Louis Crépy fils. The print was announced for sale in the November 1728 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2491.

PROVENANCE

Paris, with Eugène Kraemer. His sale, Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, April 29, 1913, lot 68: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . L’Escarpolette. Dans un parc, une jeune femme coiffé d’un chapeau de paille sur ses cheveux blonds, en corsage vert décolleté découvrant les bras jusques aux coudes, jupe de soie rouge, est assise sur une corde tendue entre deux arbres et s’y retient de ses deux mains.

A droite, un gentilhomme vêtu de soie jaune, tête nue, a saisi sa compagne au-dessous de la taille, et, le corps tendu dans un nerveux effort, donne l’élan à l’escarpolette. Au second plan, au milieu des frondaisons du parc, un portique à cariatides.

Haut., 95 cent; larg., 71 cent. Cadre en bois sculpté, du temps de Louis XV.” Sold for 29,000 francs to Georges Lévy according to an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Watson Library, Metropolitan Museum, New York.Paris, with Arnold Seligmann. Sold to Chancellor Hjalmar Constantin Linder.

Helsinki, collection of Chancellor Hjalmar Constantin Linder (1862-1921; businessman). Donated by him to the Helsinki Ateneum Museum in 1920.

EXHIBITIONS

London, Royal Academy, France in the 18th century (1968), cat. 732 (as by Watteau, lent by the Ateneum Museum, Helsinki).

Bordeaux, Paris et les ateliers provinciaux (1958), cat. 42 (as by Watteau, L’Escarpolette, lent by the Ateneum Museum, Helsinki).

Helsinki, Ateneum, Onni sulla ja suru mulla, Din lycka och min sorg [Joy for You, Sorrow for Me], (2002).

Valenciennes, Musée, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), cat. 79 (as by Watteau, L’Escarpolette, lent by the Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Helsinki).

Aarhus, Denmark, Art Museum, The Garden, End of Times, Beginning of Times (2017).

Helsinki, Rococo (2015).

Gösta, The Marquise and the Baron (2015).

Helsinki, Sinebrychoff Museum, Inspiration—Contemporary Art & Classics (Inspiraatio - Nykytaide & klassikot) (2020).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 198.

Goncourt, L’Art au dix-huitième siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), under cat. 133.

Goncourt, L'Art du dix-huitième siècle (1880), 59.

Dilke, French Painters (1899), 52.

Phillips, “A Watteau in the Jones Collection” (1908), 346.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 260; 2: 25, 28, 59, 92, 133, 150; 3: cat. 67.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 264.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 59.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 67.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 36.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. 68.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 66.

Posner, “Swinging Women” (1982), 76.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 212-13, 281, 287, 302.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 61-62.

Supinen, Sinebrychoff Art Museum, Summary Catalogue (1988), 122.

Wine, Watteau (1991), 20.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 131.

Keltanen, Sinebrychoff (2003), 100.

Keltanen, Art & Atmosphere (2013), 116.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Quite remarkably, a drawing associated with this early arabesque has survived, a study of the woman on the swing (Rosenberg and Prat 131). Although the woman in the drawing looks slightly upward and to the side, in the painting Watteau modified her gaze downward. Because the drawing, now in Stockholm, is a counterproof of the lost original study, it is in the opposite direction.

The drawing for the man pushing the swing has not survived, nor have any of the drawings that Watteau must have used to prepare the arabesque surround.

REMARKS

The early history of this arabesque is unrecorded. We do not know where it was first installed and cannot trace its whereabouts through the eighteenth century and most of the nineteenth. A considerable number of paintings attributed to Watteau and showing women on swings were sold at auction in the nineteenth century but the vagaries of their description and their lack of measurements prevent any definitive association to Watteau. Among the modern critics who accept the Helsinki painting are Macchia and Montagni, Roland Michel, and Eidelberg.

The picture now in Helsinki is only the central portion of a much larger decorative composition. It is approximately only half the size of the original, and lacks all the surrounding enframement, including the still life of rustic entertainments at the bottom and the goat head at the top. This radical alteration parallels what happened to Le Dénicheur de moineaux, now in Edinburgh, which also is shorn of the arabesque elements that originally surrounded it.

Some but not all modern critics have accepted the painting now in Helsinki as the central portion of the once larger autograph version. A few reject it. Adhémar proposed that the Helsinki painting was a “variant” and that the autograph work is the canvas that figured in the Kraemer, Porgès, and Chevillard sales (our copy 1). Posner claimed that the original is lost. Ferré quotes his colleague Saint-Paulien as saying that at best the Helsinki painting is a studio work. By ignoring the painting, critics such as Temperini and Glorieux imply that the Helsinki painting is not from Watteau’s hand.

The dating of this work shows the normal variability in determing the chronology of Watteau's oeuvre. Roland Michel dates it 1707-08, Macchia and Montagni propose c. 1708-09, Mathey dates it 1709. However, many critics would place it a few years later in his career. Adhémar dates it 1712, as does the Valenciennes 2004 exhibition. Rosenberg and Prat date the drawing that Watteau used for this painting to c. 1711-12, which means that the picture had to be that date or later.

Among those who do refer to the work, there is a tendency to focus on either the narrative scene or the arabesque surround, but rarely are the two elements considered together. The great success and notoriety of Fragonard’s Hazards of the Swing has propelled that daring image into the limelight, yet his picture depended on paintings of this theme by Pater and Lancret, and they in turn depended on Watteau’s. In fact, Watteau was especially drawn to this pleasurable activity and included women swinging in several fêtes galantes—Le Plaisir pastoral (Chantilly, Musée Condé), Les Bergers (Charlottenburg), and Les Agréments de l’été—as well as in another arabesque—La Balanceuse.

Although the practice of finding pleasure in swinging extends far back in time, its depiction in Western art does not. It became a popular theme only in the eighteenth century and, not surprisingly, its first appearances are in lesser genres. It was a subject that appealed to printmakers such as Henri Bonnart, who used the theme in a series of the Four Elements to allegorize Air. One of the first examples in French painting is a picture by Jacques van Schuppen, a French artist whose Flemish-born father and uncle, Nicolas de Largillière, probably brought him in contact with the Franco-Flemish community in Paris, a group that was highly influential in Watteau’s early career. In 1704 Van Schuppen exhibited a painting of a woman on a swing, a painting that was listed in the Salon catalogue but was otherwise unknown until recently. On its own, the Salon listing might have led us to think it was a genre painting but, now that the work has surfaced, we can see it was a decorative panel, intended to embellish an interior. It does not have an arabesque enframement, but its illusion as a stone apse, replete with an arched top, and the pile of still life elements in the foreground proclaim its decorative intent.

Claude III Audran, Design for a Ceiling (detail), Stockholm, Nationalmuseum.

The motif of a woman on a swing also appealed to other decorative artists who were Watteau’s contemporaries, including Claude Audran—for whom Watteau served as an assistant. Among Audran’s decorative designs at Stockholm are several ceiling designs featuring this subject. What a delightful idea to show a woman swinging high above the observer, but all treated decorously, unlike the women in Fragonard’s era.

Donald Posner, who was obsessed with uncovering the sexual underpinning of Watteau’s art, wrote extensively about the artist’s “swinging woman” (a silly pun from the years after sexual liberation), and referred to the poem under Crépy’s engraving, verses that draw a parallel between the back and forth movement of the swing and the inconstancy of a young woman’s heart. Yet, although Watteau’s women sit on swings, sometimes vigorously pushed as here in L’Escarpolette, or pulled, they sit demurely in place with no sense of motion. Although Posner underscores swinging’s urgency of movement, paralleling sexual activity, Watteau’s women—especially here—sit politely, their skirts undisturbed, without visible movement in their limbs. Posner argued that the verses on the engravings, often describing aspects of love, “are not just poetic conceits superimposed on realistic genre scenes.” In fact, these verses were superimposed on Watteau’s painting a decade or more after the artist’s death; they reflect the mundane ideas of a commercial poet’s repertoire but do not necessarily bear upon Watteau's intent.

Jacques de Lajoue, L’Escarpolette. Whereabouts unknown.

In an interesting comparison, Roland Michel demonstrated that a painting by Jacques de Lajoue depended on Watteau’s L’Escarpolette. This accords with what we now understand about Lajoue’s oeuvre, namely that he purloined his figures—singly and in clusters—from Jean de Jullienne’s engravings after Watteau’s paintings. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century auctions his pictures were often given to both Watteau and Lajoue, as though the two artists had collaborated on the same canvas, an erroneous tradition that Jean Cailleux disarmed. What Cailleux rightly observed was that Lajoue himself, without a collaborating partner, borrowed these figures from Jullienne's engravings after Watteau. In Lajoue’s Escarpolette, much as in Watteau’s design, the woman on the swing looks down at the man pushing it, and repeats the bagpipes, and wide-brimmed straw hat that Watteau had piled in the lower part of the arabesque. While Roland Michel was more concerned with Lajoue’s dependance on Watteau, of equal interest is the heightened emotional pitch of Lajoue’s concept: rather than sitting upright, the woman is seen at an angle as though in motion, her skirt billows and we can see beneath it. From our point of view as voyeurs, we are indiscreet but only slightly. Lajoue’s painting is halfway between Watteau’s modest presentation and Fragonard’s sexually charged explosion.

For copies of L’Escarpolette, CLICK HERE