- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

La Finette

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. M.I. 1123

Oil on oak panel

25.3 x 18.9 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

The Artful Girl

Giovane dama con arciliuto

RELATED PRINTS

La Finette was engraved in reverse for Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé by Bernard Audran, whereas its pendant, L’Indifférent, was engraved by Gabriel Scotin. The two prints were announced for sale in the July 1729 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 1603-04.

In England in the mid-eighteenth century, Thomas Ryley executed an engraving after Audran’s print of La Finette, combining it with an image after Watteau’s Le Mezzetin, the two juxtaposed seated musicians falsely forming a single composition. (Ryley copied other images from the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé, such as La Diseuse d’aventure.)

Paul-Adolphe Rajon after Watteau, La Finette, wood engraving, 1870.

An engraving after La Finette by Paul-Adolphe Rajon (1843-1888) accompanied Paul Mantz’s 1870 article in Gazette des beaux-arts.

A colored engraving after La Finette by Antoine Valérie Bertrand (b. 1823) was issued in the nineteenth century.

Timothy Cole after Watteau, La Finette, wood engraving, 1909.

Timothy Cole (1852-1931) executed a wood engraving after the Watteau painting in 1909 that was published in Century Magazine in 1916.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean-Baptiste Massé (1687-1767; painter). His ownership is indicated on Audran’s 1729 print: “Tiré du Cabinet de Mr Massé.” Neither this painting nor it’s pendant are listed in Massé’s will of 1765-67.

Bought by Charles Nicolas Cochin for Abel François Poisson, marquis de Ménars et de Marigny (1727-1781; brother of Madame de Pompadour). His sale, Paris, March 18- April 6, 1782, lot 143: “ANTOINE WATTEAU Deux Sujets faisant pendants. Ils représentent une Dame assise touchant de la mandoline sur un fond de Paysage, & un autre Paysage au milieu duquel est un homme dans l’attitude d’un Danseur, portant sur l’épaule droite un manteau rouge doublé de bleu. B. 9 pouces sur 6 & demi de large.” According to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the pair sold for 475 livres to Godefroy.

Paris, collection of Auguste Gabriel Godefroy de Villetaneuse (d. 1785; Inspector General of the Navy). His sale, April 25, 1785 (postponed until November 15-19, 1785), lot 43: “Antoine Watteau. . . Deux Tableaux faisant pendans; l’un représente une dame assise dans un jardin pinçant de la Mandoline; l’autre offre un homme qui danse. il est vêtu d’un manteau rouge doublé de bleu, attaché sur son épaule droite. Ces deux jolis tableaux viennent de M. de Ménard, no. 143, & ont été vendus 475 livres. Hauteur 9 pouces, largeur 6 pouces 6 lignes. B.” According to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, the pair sold for 490 livres.

Paris, with Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun (1748-1813: painter and art dealer). His sale, Paris, September 29-October 7, 1806, lot 130: “PAR LE MÊME [ANTOINE WATTEAU.] . . . Deux Tableaux, l’un représente une jeune Femme assise, jouant de la guitare; l’autre un jeune Danseur. Ces deux Tableaux, d’une couleur fine & brillante, nous rappellent la belle manière du Titien. Aussi les productions de ce maître font elle l’admiration de tout les yeux délicats & juges du coloris. Ils ont orné les cabnets de MM de Jullienne & Godefroy de Villetaneuse, & se trouvent gravés par B. Audran & G. Scotin sous les titres de la Finette & de l’Indifférent.—Hauteur 9 pouces, largeur 7 pouces. B.” According to annotated copies of the sale catalogue, the pair sold for 75 francs to Pierre Joseph Renout.

Paris, collection of M. His sale, Paris, May 4 ff., 1808, lot 130: “PAR LE MÊME [ANTOINE WATTEAU]. . . . Deux Tableaux, l’un représente une jeune Femme assise, jouant de la guitare; l’autre un jeune Danseur. Ces deux Tableaux, d’une couleur fine & brillante, nous rappellent la belle manière du Titien. Aussi les productions de ce maître font elles l’admiration de tout les yeux délicats & juges de coloris. Ils ont orné les cabinets de MM. de Jullienne & Godefroy de Villetaneuse, & se trouvent gravés par B. Audran & G. Scotin sous les titres de la Finette & de l’Indifférent.—Hauteur 9 pouces, largeur 7 pouces. B.”

Paris, collection of Dr. Louis La Caze (1798-1869; physician); in his collection by 1848. Donated to the Musée du Louvre in 1869.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Association des artistes, Troisième exposition (1848), cat. 140 (as by Watteau, La Finette, lent by M. Lacaze).

Paris, Galerie Martinet, Collections d’amateurs (1860) cat. 271 (as by Watteau, La Finette, collection of M. Lacaze).

London, Royal Academy, French Art 1200-1900 (1932), cat. 193 (as by Watteau, La Finette, Musée du Louvre).

Paris, Petit Palais, Chefs d’oeuvre de la peinture française du Louvre (1946), cat. 297 (as by Watteau, La Finette).

Paris, Hôtel de la monnaie, Pélérinage à Watteau (1977), cat. 37.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 58.

Faroult and Eloy, La Collection La Caze (2007), 75, 114.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 46.

Clément de Ris, “Troisième exposition” (1848), 194.

Mariette, Abecedario (1853-62), 6: 108.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 47.

Mantz, “L’École française” (1859), 351.

Thoré-Bürger, “Exposition de tableaux” (1860), 268-69, 272-73.

Goncourt, L’Art au dix-huitième siècle (1860), 57.

Godard, “Exposition de Peinture” (1860), 333-34.

Lejeune, Guide théorique et pratique (1864), 447.

Cousin, Le Tombeau de Watteau (1865), 28.

“Etat des tableaux de la collection La Caze” (1869), n.p.

Mantz, “La Collection La Caze” (1870), 12.

Guiffrey and Courajod, “Documents sur la vente de la collection du marquis de Ménars” (1873), 396.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 83.

Paris, Louvre, Tableaux légués par M. La Caze (1871), 71.

Goncourt, L’Art du dix-huitième siècle (1880), 51, 57.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 3, 65.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 115, 175.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 38, 64, 72.

Dilke, French Painters (1899), 83, 85, 89.

Fourcaud, “L’Existence de Watteau” (1901), 256-57.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 69-70, 79, 82, 128.

Legrand, Les Donateurs du Louvre (1902), 13.

Paris, Louvre, Catalogue sommaire des peintures (1903), 93.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 87, 122, 288, 401-03.

Josz, Watteau (1904), XII, 34, 52, 178-79.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), 28, 43, 74, 89, 103-04.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), 176.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 70, 134-35, 263; 2: 29, 58, 62, 96, 132, 151, 161; 3: cat. 128.

Seailles, Watteau (1927), 84.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 93.

Gillet, La Peinture au Musée du Louvre (1929), 38.

Wilenski, French Painting (1931), 107, 112, 114.

London, Royal Academy, French Art (1932), cat. 193.

Ratouis de Limay, “Trois collectioneurs” (1938), 78.

Paris, Petit palais, Chefs d’oeuvre de la peinture française du Louvre (1946), cat. 297.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), 28-29, 34, 36, 153, cat. 128.

Mathey, “Le Rôle décisif des dessins” (1959), 40.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 69.

Mirimonde, “Musiciens isolés et portraits” (1966), 143.

Brookner, Watteau (1967), 34.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 158.

Pouillon, Watteau (1969), under no. III.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A 16.

Compin and Reynaud, Catalogue des peintures (1972), 398.

Wilenski, French Painting (1973), 103.

Paris, Louvre, Catalogue illustré (1974), 68, 227, n° 920.

Haskell, Rediscoveries in Art (1976), 18.

Banks, Watteau and the North (1977), 84.

Paris, Musée de la monnaie, Pèlerinage (1977), 269.

Ferré, Watteau (1980), 24.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 198.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 137-38, 254, 273, 291.

Compin and Roquebert, Catalogue sommaire (1986), 4: 285.

Edwards, “Watteau and the Dance" (1987), 219.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), 2: cat. 481.

Lallement, “Inventaire des tableaux à sujets musicaux" (1997), cat. 149.

Börsch-Supan, Watteau (2000), 78.

Cohen, Art, Dance, and the Body (2000), 207.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 74.

Rosenberg, Dictionnaire amoureux du Louvre (2007), 893-96.

Gordon, The Houses and Collections of the Marquis de Marigny (2003), 37, 231, 303.

Faroult and Eloy, La Collection La Caze (2007), 679-80.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 231-33.

Martin, Raymond, and Sahut, “Tableaux du Louvre” (2009), cat. 12.

Marsat, “Les Techniques d’imagerie scientifique” (2009), 76-81.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 168, 171.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau, Sheet of Studies, red, black, and white chalk, 23 x 35.3 cm, Paris, École national supérieure des beaux-arts.

A sheet of miscellaneous studies in the collection of the École national supérieure des beaux-arts (Rosenberg and Prat 481) was the ultimate source of inspiration for Watteau when he came to paint La Finette. In this drawing the model’s dress is fully delineated, but her face and theorbo are barely indicated. This suggests that Watteau may have relied on other, separate drawings that depicted these missing elements.

More problematic is plate 54 of the Figures de différents caractères, the two-volume set of engravings after Watteau’s drawings commissioned by Jean de Jullienne. The figure in this particular engraving, executed by Benoît Audran, is almost identical to that in La Finette. Normally these engravings record Watteau drawings, and one would normally expect it to be after the drawing in Paris, but the engraving shows the woman’s fully delineated face, hat, and theorbo–elements not present in the Paris drawing. Was there a more developed drawing that the engraver was recording? This seems to be the case. Less likely, Audran may have relied on an oil counterproof pulled from a preliminary state of the painting.

Some critics, such as Rosenberg and Prat, have argued that Audran copied the figure in the painting itself but this seems improbable. It was expressly stated at the time that the plates in the Figures de différents caractères were copied from drawings, and there is no reason to believe that the engravers deviated from this very specific program.

REMARKS

Since the early eighteenth century, La Finette has been paired with L’Indifférent. They have the same support and, in fact, a 2009 analysis undertaken in the Louvre laboratory found that the two panels are cut from the same board. Each presenting just one figure, they complement each other in subject and composition. La Finette presents a woman with a large stringed instrument, and despite it having been misidentified in the past as a guitar, a mandolin, or a lute, it is now recognized to be an Italian theorbo, an instrument that appears in other Watteau drawings and paintings. When seen in relation to L’Indifférent, La Finette could be viewed as providing the music to accompany the man’s dancing (his feet are in fourth position, his arms in second position). Some have termed the pair allegories of music and dance, though this seems to over do the argument.

Other critics have seen La Finette and its pendant as portraits of specific people. Laroche, for example, claimed that they portray Marie Louise and Pierre Henri Sirois. Also Wilenski sought to identify La Finette as Sirois’ daughter. Judging by the preliminary drawings, however, the figures show nothing more than the types of anonymous models he posed in the studio.

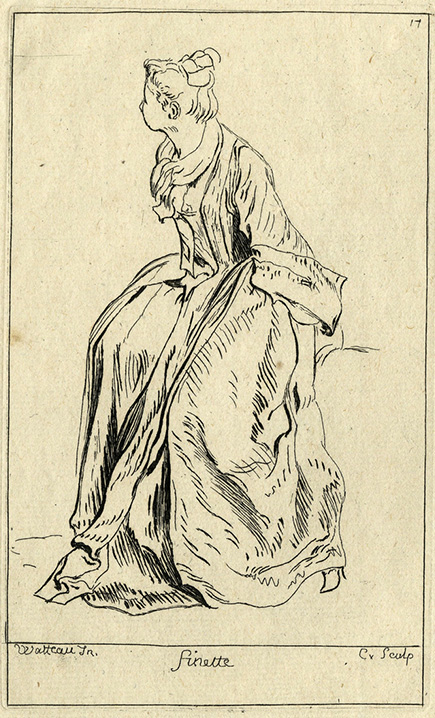

A.C. de Caylus after Watteau, Finette, etching, Suite de figures inventée par Watteau, plate 17.

More pertinent and persuasive, Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold have pointed out that La Finette is a theatrical character who appears in several pieces by Florent Dancourt in the early eighteenth century: Fêtes (1699), La Famille à la mode (1699), Enfans de Paris (1704), and Le Moulin de Javelle. Her role was that of a “soubrette intelligente et honnête.” This should not imply that Watteau intended to represent this theatrical character since, after all, the titles employed in the Oeuvre gravé were created after the artist’s death. It was Jean de Jullienne and his team of literary men who made this association. Interestingly, the comte de Caylus titled an etching after a Watteau drawing of a seated woman as “Finette.”

Rosenberg (2007) and others have viewed Watteau’s La Finette as possessing a very different connotation–as an emblem of pronounced sexuality. Noting that when musicians and dancers are pendant images, the man normally plays the instrument while the woman dances, but our pendants have just the opposite arrangement: it is claimed that the woman is a “feisty instrumentalist” holding “a hefty instrument” and thereby appropriating “the phallic spirit of the male musicians.”

Benoît Audran after Watteau, La Fileuse, engraving.

Watteau, La Polonnaise assise, oil on panel, 23.2 x 17 cm. Chicago, Art Institute.

As opposed to Watteau’s more complex fêtes galantes and theatrical scenes, La Finette and L’Indifférent are somewhat unusual for their small size and single figures. But they are not unique. Other Watteau pictures share this modest format and uniformity of size and support, works such as La Fileuse, La Marmotte, Le Docteur, La Polonnaise debout, and La Sultane. Especially close counterparts are the seated women in La Polonnaise assise and L’amante inquiète. This format of a single figure against a landscape is also present in Watteau’s etchings for his Figures français et comiques. While not that common in French painting, this compositional format often appears in earlier Flemish art, as in many of David Teniers’ paintings of peasants, such as his Allegories of the Four Seasons in the National Gallery, London.

A pensive mood pervades both La Finette and L’Indifférent. Both characters are unusually introspective—almost unaware that they are playing music or dancing. If the air is poetic, it cannot be described as happy or joyous. Their mood is reinforced by the somber colors, which brings us to consider the physical condition of the pictures. Although frequently praised for their rich Venetian color in early nineteenth-century sale catalogues, this no longer seems true. A comparison of La Finette with the Jullienne engraving establishes how vaguely delineated the landscape has become. Indeed, as far back as the eighteenth century, Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714-1780) noted that the two pendants had been over-cleaned. Also the paintings may have suffered at the hands of La Caze and then by J.G. Goudinat, chief of the Louvre restoration department who worked on the paintings after L’Indifférent was returned following its theft in 1939. Not without reason, Rosenberg described the condition of La Finette as “worn,” and Brookner went still further, describing it as “rubbed almost to the point of no return.”

In 1984 Rosenberg remarked on the relative unanimity of critics in dating La Finette: “all of the scholars placed them [the pendants] between 1716 and 1718, with the majority opting for 1717.” While it is true that Mathey, Macchia and Montagni, Roland Michel, Börsch-Supan, and Temperini, all chose the date 1717, Adhémar preferred an earlier range of c. 1712-1715.

For copies of La Finette CLICK HERE