- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

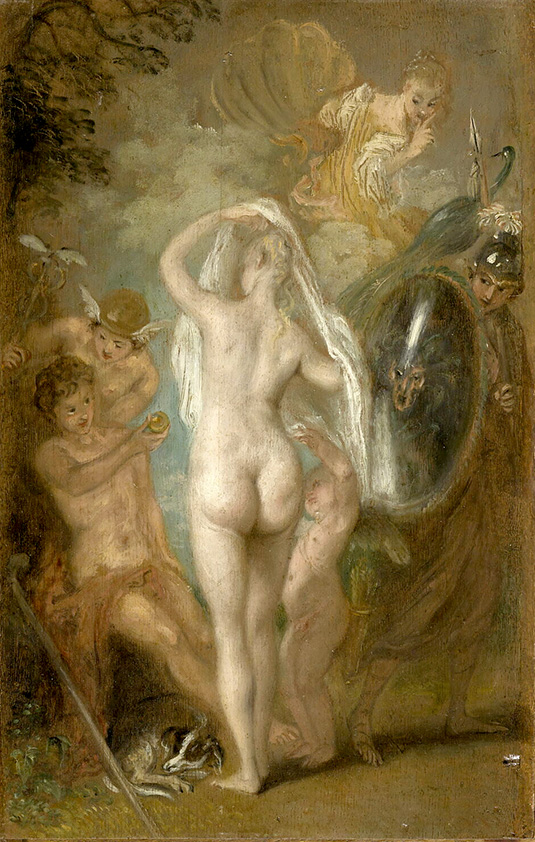

Jugement de Pâris

Entered July 2025

Paris, Musée du Louvre, MI 1126

Oil on oak panel

47 x 31 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Il giudizio di Paride

Judgment of Paris

RELATED PRINTS

Le Jugment de Pâris was not includedin the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé.

PROVENANCE

Probably Paris, collection of Monsieur A***. His sale, Paris, January 17, 1803, lot 237: “Le Jugement de Pâris, Esquisse, par Watteau. 17 p. sur 12. B.” Sold for 16 francs.

Paris, collection of Dr. Louis La Caze (1798-1869, physician). Listed in the 1869 inventory of his collection: “156: WATTEAU. Le jugement de Pâris (esquisse). (1er cabinet après ma chambre sur le jardin.)” Bequeathed to the Louvre, 1869.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Paris, Louvre, Tableaux légués par M. La Caze (1871), cat. 265.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), 52.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 62.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 89, 176.

Fourcaud, “L’existence de Watteau” (1901), 255-56.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 129.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 350, 398.

Phillips, “An Unknown Watteau” (1904), 235-36.

Deux heures au Musée du Louvre (1910), 205.

Rodin, L’Art (1911), 151.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), 52, 106, 126.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), 180, pl. 107.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 61.

Brière, Louvre, catalogue de peintures (1924), cat. 988.

Ingersoll-Smouse, Pater (1928), cat. 569.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 7.

Gillet, La Peinture au Louvre (1929), 40-41.

Van Puyvelde-Lassalle. Watteau et Rubens (1943), 23.

Godfrey, “L’Amor sacro e l’Amor profano” (1949), 63-64.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), 89, cat. 214.

Rodney, Judgment of Paris (1952), 65-66.

Dumont, “Le musée imaginaire” (1957), 62.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 69.

Schefer, “Visible et thématique chez Watteau” (1962), 50.

Chatelet and Thuiller, French Painting (1963), 164.

Brookner, Watteau (1967), 39.

Béguin, “Le Docteur La Caze et sa collection” (1969), 7.Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 210.

Sgard, “Style Rococo” (1970), 16.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A33.

Boerlin-Brodbeck, Watteau und das Theater (1973) 99, 197, 225.

Posner, A Lady at Her Toilet (1973), 26, 73.

Wilenski, French Painting (1973), 105.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Catalogue illustré (1974), 2: 173, 228, cat. 926.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Catalogue sommaire illustré (1986), 286.

Paris, Musée du Louvre, Catalogue des peintures (1972)

Erné, “Watteau“ (1975), 18-20.

Mirimonde, Iconographie musicale (1977), 2: 81.

Ferré, Watteau (1980), 33.

Hagstrum, Sex and Sensibility (1980), 284-85.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), 18, cat. 133.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 151.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 201.

Lille, Musée des beaux-arts, Au Temps de Watteau (1985), under cat. 124, 163.

Bergeon, “Quelques points” (1987), 136-138.

Faillant-Dumas and Rioux, “Etude de quelques peintures” (1987), 129, 130, 134.

Moutsopoulos, “Les structures de la temporalité” (1987), 147.

Démoris, “Watteau, le paysage et ses figures” (1987), 161.

Moureau, “Le tableau libertin” (1993), 92, 93, 95.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 133, cat. 114.

Valenciennes, Musée, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), 49, 51.

Marx, Arte per i Re (2004), 316.

Rosenberg, Raphael and France (2005), 75.

Arasse, Histoires de peintures (2006), 226.

Faroult and Eloy, La Collection La Caze CD-ROM (2007), 686-687.

Rosenberg, Dictionnaire amoureux du Louvre (2007), 508.

Cheng, Pèlerinage au Louvre (2008), 86.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 118.

Martin, Raymond, and Sahut, “Tableaux du Louvre” (2009), 18.

Eveno et al., “Palette de Watteau” (2009-10), 40, 41, 46-47.

Jaunard et al., “Panneaux de bois chez Watteau, Lancret et Pater” (2009-10), 52, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 (n. 16, 18, 19, 21).

Aitken, “Aux sources de Cythère” (2009), 70, 71, 75 (n. 10)

Volle, “Les restaurations des tableaux de Watteau” (2009), 105, 106 (n. 44).

Galard, Promenades au Louvre (2010), 574.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 186, 307.

Pomarède, Les Belles du Louvre (2012), 19, 40, 46.

Louvre, Toutes les peintures (2012), 552.

Bronfen, Crossmappings (2018), 39-40, 398.

Chantilly, Musée Condé, Les Mondes de Watteau (2025), 148.

RELATED DRAWINGS

There are no known preparatory drawings for Le Jugement de Paris.

REMARKS

Although primarily known for his fêtes galantes and theatrical subjects, Watteau was occasionally drawn to mythological themes. Indeed, these occasions are more frequent than might have been thought. There are traditional easel paintings such as Sommeil dangereux, Diane au bain, Vertumne et Pomone, and the landscape Acis et Galathée.

Some of the mythological paintings were evidently intended for decorative purposes such as the Crozat Saisons, and the Louvre Nymphe et satyre. Perhaps the greatest number of mythological depictions are included in his arabesques such as Les Singes de Mars. Not to be overlooked are the several paintings with putti and emblems of the classical gods, such as Les Enfants de Sylène, Les Enfants de Bacchus, and L’Amour mal-accompagné.

Despite these many mythological works by Watteau, Le Jugement de Pâris still stands out as exceptional, not merely for its subject but also its style. Unlike the other mythologically-themed works that have been cited, the Jugement de Pâris is a freely, very lightly painted picture. Indeed, often in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was described as a “sketch.” This is still true today, and many scholars refer to this work as a sketch. One normally associates “sketch” with the idea of a preliminary phase for a larger, more finished work, but this would not seem to be the case here. Was the artist perhaps emulating Rubens who made such oil sketches often on panel, in pale colors, and as freely painted? Pierre Crozat owned several such oil sketches on panel by Rubens. But whereas Rubens’ oil sketches were preliminary to larger, more finished works, Watteau’s Jugement de Pâris was apparently an end in itself.

The theme of the Judgment of Paris has been a staple in European art since the Renaissance. Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving after a Raphael drawing is perhaps the grandfather of all the different variations that subsequent artists introduced, though Raphael’s drawing was itself closely dependent on a Roman relief. Rubens’ several compositions with this theme are worthy descendants of Raphael’s design. Whether by masters or students, these paintings show a remarkable coherence. Invariably arranged as a horizontal frieze, much like the original Roman relief, the trio of competing goddesses stand opposite a seated Paris. While Watteau’s painting is vertical rather than horizontal, and its characters are only slightly indebted to the traditional groupings, still, something of this pictorial traditional remains. Yet, typical of Watteau, he transformed it into something new. As in earlier renderings, one of the goddesses is standing close to the front, largely nude but modestly draped. Paris’ dog rests in the shadows. Breaking with tradition, Watteau depicts Hera and Juno not standing next to Venus as in most earlier renderings but rather fleeing into the distance.

In Watteau’s time, one of Rubens’ three major renderings of the Judgment of Paris hung in the Palais royal. As a guest of the duc d’Orléans, Watteau evidently admired the work; a drawing after figures in the Orléans painting testifies to his admiration of it (Rosenberg Prat 246). It is a study of two motifs from opposite sides of Rubens’ painting: Paris’ recumbent dog and a kneeling putto. The artist may well have made other studies but those drawings seem not to have survived.

There is little information about the early provenance of Watteau’s painting. This is particularly frustrating because it would be interesting to know which of Watteau’s friends or patrons was involved, because it seems to be an intimate work, not one produced for the general public.

One of our first possible sightings of Watteau’s Jugement de Pâris is in an anonymous 1789 sale (Paris, May 6, lot 13), where it was paired with another of the artist’s pictures. The paintings were described as “Deux Tableaux très-colorés à l'imitation des beaux ouvrages de Rubens, l'un représente Vénus recevant la pomme que lui présente l'Amour, l'autre deux Bacchantes occupées à cueillir des raisins. Haut. 20 pouces, largeur 14 pouces. T.” Roland Michel proposed that this unnamed pendant was Vertumne et Pomone, a Watteau painting recorded in Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé. That work, extant today, depicts Vertumnus, goddess of seasonal change, disguised as an aged woman and trying to attract the attention of the fair Pomona, protector of fruit trees and gardens.The large bunch of grapes and pumpkin at the goddess’s feet serve as her attributes. But was the Vertume et Pomone actually paired with Le Jugement de Pâris? The 1789 auction catalogue describes the second picture as showing two standing bacchants, yet only one is standing in Watteau’s composition. Likewise, while the 1789 catalogue describes the women as occupied gathering in grapes (“occupées à cueillir des raisins”), neither woman is shown harvesting. While the two works are on wooden panels (the 1789 catalogue claims they are on canvas), and are relatively comparable in size and, not least, both have mythological themes, they nonetheless form an unlikely pair. The compositions are not compellingly close, and their subjects have little in common other than that they are mythological. If the two paintings had been together since the start, is it not curious that Jullienne’s engravers reproduced Vertumne et Pomone, but ignored the adjacent Jugement de Pâris–if indeed the two paintings were together then. By the early nineteenth century the two paintings were no longer together.

Scholars have sought to trace the nineteenth-century whereabouts of the Jugement de Pâris prior to its appearance in the La Caze collection, but this remains a murky area. All that can be safely concluded is that it was hidden from sight during much of that century. A Jugement de Pâris was sold from the collection of the noted tenor, Paul Barrroilhet (March 10, 1856, lot 55, as by Pater). It was bought in, and then put up for auction on April 2, 1860, (lot 117, as by Lancret). This picture was ascribed to Pater and Lancret— possible alternatives for a painting in the style of Watteau—yet no such mythological subject can be associated with either Watteau satellite. However, neither the 1850 or 1856 picture was measured or described more fully, which makes it difficult to identify those paintings. Despite the persistent assertions of modern scholars that the Barroilhet painting is the one now in the Louvre, this too cannot be the case. When the painting sold in 1856, it was bought by the painter Nicolas Henri Gustave Mailand and it remained in his collection until it was auctioned on May 2, 1881 (lot 150). This was more than a decade after La Caze ’s picture had entered the Louvre.

Just as all scholars have accepted the attribution of the Louvre panel, so too they agree that the picture is a work of Watteau’s maturity. Exceptionally, Roland Michel proposed c. 1714-15 but most scholars have called for a later date. Mathey preferred 1717-21, Rosenberg favored c. 1718, Temperini selected c. 1718-20, Montagni and Macchia chose 1720, Adhémar placed it among his last works, c. 1720-21, Brookner was so bold as to specify the spring of 1721.

For copies of Jugement de Pâris, CLICK HERE