- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

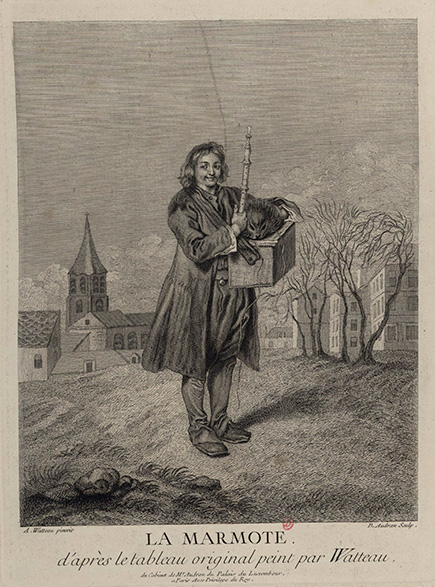

La Marmote

Entered December 2025

St Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, inv. 1148.

Oil on canvas

40 × 32.2 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Jeune savoyard

Jeune savoyard avec un marmot

Marmot

La Marmotte

Montreur de marmotte

Un Petit savoyard

Il savolardo

Le Savoyard

Savoyard avec sa marmotte

Savoyard debout avec sa marmotte

Savoyard with a Marmot

Savoyarde mit Murmeltier

RELATED PRINTS

Benoît II Audran after Watteau, La Marmote, engraving, c. 1732.

La Marmote was engraved in reverse by Benoît II Audran for Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé . It appears on the same sheet as its painted pendant, La Fileuse. The engraving was announced for sale in the December 1732 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2866).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Claude III Audran (1658-1734; artist). Audran’s ownership is indicated on the engraving by his nephew, Benoît II Audran: “du Cabinet de Mr Audran du Palais du Luxembour [sic].” The painting is cited, with its pendant, without attribution, in the 1734 posthumous inventory of Audran’s estate: “Item deux tableaux pendants représentants l’un une marmote et l’autre une bergère prisé cinquante livres” (Paris, Archives nationales, MC/ET/XLIX/553, fol. 5 recto). Thence by inheritance to Jean Audran (1667-1756, engraver) (after the refusal of the inheritance by his brother Gabriel, 1659-1740, MC/ET/XLIX/553, fol. 21 verso. Although Jean kept paintings from Claude III, it seems he did not keep La Marmote or La Fileuse. His inventory mentions “Item deux tableaux paysages un Téniers et un Vateau en bordures dorées prisées quarante huit livres” (MC/ET/XCII/715, fol. 14 verso), but this does not seem to refer to La Marmote or La Fileuse. It is possible that La Marmote and La Fileuse were sold after Claude III’s passing, since neither of the pendants can be found in Jean Audran’s estate, or in the collections of his descendants.

Paris, collection of Marie Jeanne Horguelin, countess of Redern (1717-1788), together with La Fileuse (according to the post-1772 transcript of a document once in the Jules Desnoyers collection published by Fréville in 1888). The two paintings are listed in this estimate. La Marmote is described as a “Montreur de marmottes par Watteau. 300 livres” and La Fileuse as “Bergère de Watteau. 240 livres”. Curiously, the plural form for "marmote" is used.

St. Petersburg, collection of Catherine II (1729-1796; empress of Russia). It was purchased before 1774. At the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg c. 1875; by 1912 moved to the Gatchinova Palace; transferred to the Hermitage Museum after the Russian Revolution.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Palais national, Chefs d ’oeuvre (1937), cat. 226 (as by Watteau, lent by the Hermitage).

Moscow, Pushkin Museum, (1955), cat. 1148 (as by Watteau, Savoyard with a Marmot, lent by the Hermitage).

Leningrad, Hermitage (1956) (as by Watteau, Savoyard with a Marmot, lent by the Hermitage).

Leningrad, Hermitage (1972) cat. 32 (as by Watteau, Savoyard with a Marmot, lent by the Hermitage).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 32.

Bailey et al, The Age of Watteau (2003), cat. 2.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

St. Petersburg, Hermitage, Catalogue (1774), 3: cat. 2048, 118.

St. Petersburg, Hermitage, Livret (1838), room XLV, cat. 6.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 40.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 40.

St. Petersburg, Hermitage, Catalogue (1863), cat. 1502.

St. Petersburg, Hermitage, Catalogue (1871), cat. 1502.

St. Petersburg, Hermitage, Catalogue (1887), cat. 1502.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 85.

Mollett, Watteau (1883), 66.

Fréville, “Estimation de tableaux” (1888), 64.

Somov, Catalogue de la galerie des tableaux (1903), cat. 1502.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures théâtrales” (1904), 353.

Josz, Watteau (1904), 222, 389.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), p. 185, pl. 1.

Mathey, “Les Premiers amateurs” (1921), 121.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 122.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 164.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 13, pl. 10.

Mathey, “Remarques sur la chronologie” (1939), 154-56.

Brinckmann, Watteau (1943), 15.

Kunstler, Watteau, L’Enchanteur (1936), 5.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 13.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1957), cat. 490.

Sterling, Great French Paintings (1958), 40.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 24.

Descargues, Le Musée de l’Hermitage (1961), 164.

Chatelet and Thuillier, French Painting (1963), 162.

Nemilova, Watteau et amis (1964), 156-57.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 61-66 ; 161-64.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 142.

Munhall, "Savoyards" (1968), 90-91.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B 87.

Levey and Kalnein, Art and Architecture (1972), 16.

Nemilova, “Contemporary French Art” (1975), 432.

Posner, “An Aspect of Watteau“ (1975), 279-86.

Banks, Watteau and the North (1977), 132-35.

Mirimonde, L’Iconographie musicale sous les rois bourbons, 2 (1977), 64-65.

Guerman, Antoine Watteau (1980), 11.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 182.

Nemilova, Peinture française (1982), 137-39.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 156.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 27-31.

Nemilova, French Painting of the Eighteenth Century (1986), 453-54.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 294.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 62.

Paris, Louvre, Watteau et l ’art de l ’estampe (2010), under cat. 31, 122.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 243.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), 22, under cat. 111.

Plomp and Sonnabend, Watteau: Der Zeichner (2016), under cat. 27-28.

Chantilly, Les Mondes de Watteau (2025), under cat. 30.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau, Study of a Standing Marmoteer, red and black chalk, 32.1 x 20 cm. Paris, Musée du Petit Palais.

Watteau (?), Study of a Standing Marmoteer, red and black chalk counterproof, 31.3 × 17 cm. Whereabouts unknown.

Until recently it was believed that La Marmote was based on a red and black chalk drawing in the Petit Palais, but used in reversed (Rosenberg and Prat 294). Several decades ago a supposed counterproof of the Paris drawing appeared at auction (London, Christie’s, December 17, 1998, lot 16) and it was assumed that this was the model that the artist used for his painting. However, the matter is less than certain. The newly discovered counterproof is exceptionally weak and unconvincing, and its authenticity needs to be considered more carefully.,

The drawing and its supposed counterproof are part of a dozen studies of savoyards. Almost all of them pose the figure against a blank background or a very minimal landscape. A cursory indication of trees is present at the left in the Paris drawing for La Marmote, but in the painting a view of a town and a grove of trees form a frieze that stretches across the composition.

Watteau, Landscape with a View of a Distant Town, red chalk and watercolor, 16.2 × 22 cm. Haarlem, Teylers Museum.

Some scholars have rightly pointed to the resemblance between the church in La Marmote and one in a watercolor in the collection of the Teylers Museum (Rosenberg Prat 135). Both edifices have towers with strong,, squarish bases. Also, the church is situated at the right in the Teylers drawing and countering it is a small grove of trees on the opposite side. This is somewhat like the arrangement in the painting.

REMARKS

Benoît II Audran, La Fileuse, engraving, c. 1732.

Originally La Marmote was coupled with a pendant, La Fileuse, a picture showing a country woman with a distaff. The same compositional formula was used for both: a central figure facing the viewer and a distant townscape running across the background. The two paintings were together in Claude III Audran’s collection when they were engraved by Benoît Audran in 1732. They were probably still together after 1772, as shown by the listing of two Watteay paintings in the estimate of countess Redern‘s collection, where they are referred to as “La Bergère” and “Montreur de marmottes.” At some point before 1774, the pendants were separated; La Marmote entered the Russian royal collection while La Fileuse went for auction in 1776 (see the entry fo La Fileuse).

Jaques Callot, The Captain, c. 1620, engraving

David II Teniers, A Man Walking, 26 × 20.5 cm. San Francisco, Art Museums.

Intrigued by the compositional formula used in La Marmote and La Fileuse, scholars have sought to establish the pictorial source that may have inspired Watteau. Some have pointed to the work of Jacques Callot, while others have preferred David Teniers. Although from different centuries and different artistic traditions—one Mannerist, the other Baroque realism—these examples share the same idea of a large central figure towering over a landscape that set on a much smaller scale. While we cannot prove which source Watteau turned to, it does establish the basic truth that Watteau was responsive to older, established traditions. Collectors in the early eighteenth century, like Pierre Crozat, greatly favored Flemish painting, and that taste helps explain why Watteau and his contemporaries painted scenes echoing those represented by artists such as Teniers.

Until recently there had been little attempt to see more in La Marmote and La Fileuse than just a straightforward representation of popular types. However, criticism of the last decades has attempted to impart a sexual overlay on these works. The cylindrical shape of the man’s flute and the woman’s spindle have been characterized as phallic, while there is a linguistic tradition associating a marmot with a woman’s vagina. Once pronounced, this type of interpretation has been seized upon by most contemporary critics. However, this line of thought seems questionable, especially since it is foreign to the whole of Watteau’s oeuvre. Not least, Watteau’s sexual identity is uncertain, yet it should be central to such hypotheses.

As with so many paintings by Watteau, there has been much discussion as to its date. At first, because of its ties to Flemish art, it was presumed that it was painted early in his career when Watteau was emerging from the traditions of his native Hainault. Staley, for example, dated it 1702 when Watteau first arrived in Paris. Adhémar placed the picture between 1703 and 1708. Others dated the paining a few years later, when he worked for Claude III Audran—the first known owner of the paintings. Banks favored an early date of c. 1705-08. Advancing the date still later, Mathey proposed c. 1713 on the basis of the preparatory drawings for this painting. Still others have assigned it a later date of c. 1715-16, including Rosenberg, Roland Michel, Temperini, Plomp and Sonnabend. Glorieux also favored c. 1716. Saint-Paulien, ever erratic in his attributions, challenged the authenticity of the Hermitage painting, claiming that is a copy based on the Audran engraving but his claim is baseless.