- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

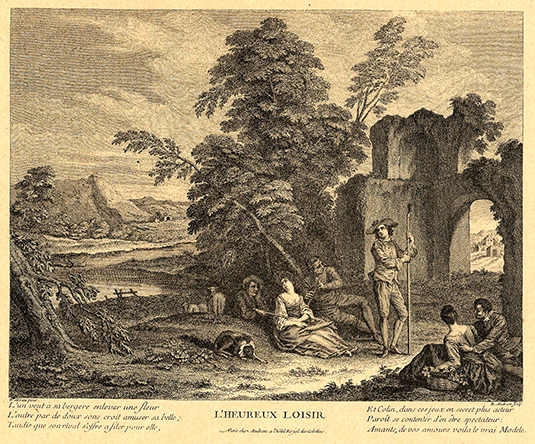

X. L’Heureux loisir

Presumed lost

Materials unknown

Measurements unknown

RELATED PRINTS

Bernard Audran, L’Heureux loisir, c. 1738, engraving.

This pastoral subject was engraved in reverse by Bernard Audran. The print was announced for sale in the July 1738 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 1607, but was not part of the original Oeuvre gravé published by Jean de Jullienne.

PROVENANCE

The Audran engraving bears no indication of the picture’s ownership and, as far as can be determined, there is no record of its appearance in any sale or exhibition in subsequent years, not in the eighteenth, nineteenth, or twentieth centuries. Without the engraving, there would be no evidence of the painting’s existence.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Cellier, Watteau (1867), 83.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 145.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 69.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 2: 44, 55, 64, 143; 3: cat. 288.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 137.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 89.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 66.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 51.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 90.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 166, 511.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 211.

RELATED DRAWINGS

A drawing in an English private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 166), one of three studies that originally were apparently parts of one sheet, corresponds to the standing “shepherd” near the center of L’Heureux loisir. When one compensates for the revered direction of the engraving, the correspondence becomes exact. Like the other figures in this work, he is an actor playing the part of a shepherd.

Audran, L’Heureux Loisir (detail).

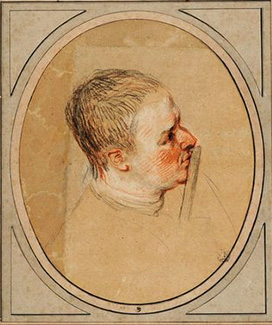

Watteau, Head of a Flutist, red, black, and white chalk, graphite, 18.2 x 15.4 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

Watteau, Studies of a Reclining Man and a Flutist (detail), red, black, and white chalk, 25 x 34 cm. Whereabouts unknown.

It has been proposed that the flutist in L’Heureux loisir was based on a drawing of the head of a flutist in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 511); this sketch evidently was cut from a larger sheet with other such studies. However the same or similar flutists appear in other Watteau drawings, such as a trois crayons sheet whose whereabouts are unknown (Rosenberg and Prat 536); there the musician’s legs are crossed much as in L’Heureux loisir.

REMARKS

Wherever the painting was after it was engraved in Paris in the early eighteenth century, it was not recorded or commented upon. It was not mentioned again until the era of Edmond de Goncourt. Typical of his thoroughness, he knew of the engraving even though it was not part of the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé. But he had essentially no information to add. Subsequent scholars have continued to list the work, including Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Réau, Adhémar, Macchia and Montagni.

On the basis of the engraving and related drawings, modern scholars have dated L’Heureux loisir, but with very different conclusions. Because of its rural subject matter, Mathey proposed c. 1707-08, and he claimed that it was at the cusp marking the divergence between traditional pastorales and the emergence of the fête galante. Macchia and Montagni, as well as Roland Michel, preferred c. 1710. On the other hand, looking at the related drawings, other scholars have proposed a much later dating. Grasselli and then Rosenberg and Prat placed the study of the standing actor c. 1712, which implies that the painting would be still later.

Underlying these various considerations is the belief that the painting was executed by Watteau. The caption on the engraving states “Watteau pinx.” Also, when the print was first advertised in 1738, the picture was declared to be “peint par Watteau.” However, there are serious reasons to doubt the ascription to Watteau. First, elements of the composition do not match what we normally find in Watteau’s work. Above all, the repeated diagonal elements stand out. Not only is the tree trunk in the lower left corner atypical of Watteau, but it is paralleled by the diagonal accent of the sapling in the middle of the composition. Equally unusual, the way in which the aggressive shepherd and maiden in the lower right act as repoussoir elements, creating a wedge in that corner to weight the picture on that side. This compensates for the vast, open expanse at the other side, but this is not the way that Watteau ordered his compositions.

Audran, L’Heureux loisir (detail).

Pierre Antoine Quillard, A Fête Galante with Bathers (detail), Philadelphia, Museum of Art.

Similarly, the figures betray the hand of an artist other than Watteau’s. While their poses derive from Watteau’s, their execution suggest the work of another artist. The way that the figures twist and turn, and the preference for inclined torsos and heads, are atypical of Watteau’s work. Although the standing shepherd may be based on the Watteau drawing in Kent, there is a wide gulf between them. Watteau's spritely character is young and vivacious whereas his counterpart in L’Heureux loisir is somewhat melancholic and unmoved. Indeed, the facial expressions, especially the deep-set, sorrowful eyes, evoke parallels in Quillard’s paintings. This is not to imply that L’Heureux loisir was executed by Quillard, though this remains a possibility. If nothing else, it points out how far the work is from Watteau’s hand.

The vaulted ruin behind the figures is another disquieting element. Although Watteau occasionally incorporated ruins in his paintings, notably in early works such as La Promenade sur les remparts and La Ruine, those buildings are of impressive scale. Here the building is curiously small, so small that the characters are taller than the arched doorway.

If the painting is not by Watteau, this raises the questions of exactly who painted it and how did it come to be engraved under Watteau’s name? It has become increasingly clear that there was a lively market for Watteau-like paintings in Paris, and this demand was met by a host of minor painters that extends beyond such well-known figures as Pater and Lancret. Their oeuvres are yet to be properly examined.