- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

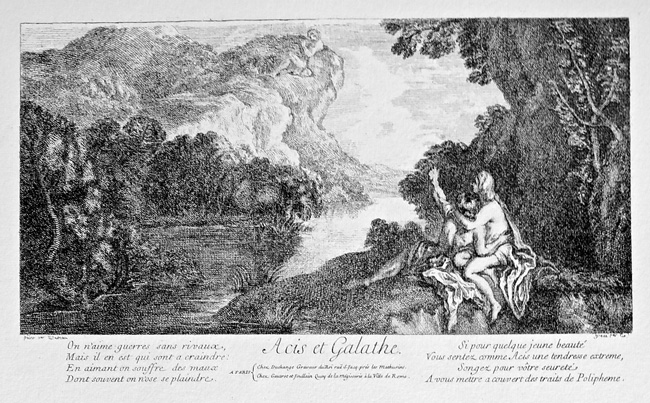

Acis et Galathée

Entered March 2014; revised May 2017

Presumed lost

Oil on canvas

50.8 x 96.5 cm

RELATED PRINTS

This picture and its pendant, La Chasse aux oiseaux, were etched by the comte de Caylus at an uncertain date, probably between 1720 and 1730. They were subsequently finished with a burin by François Joullain and incorporated into Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Charles Antoine Coypel (1694-1752; painter and director of the Académie royale de peinture). His sale, Paris, April 1753, lot 81: “Deux Paysages de même grandeur & pendants, peints sur toile par Antoine WATEAU, qui paroît y avoir voulu imiter la maniere de Forest; l’un représente une Chasse aux oiseux, & dans l’autre est Acis & Galathée: ils ont été graves par le Sieur Joullain, & sont d’un grand effet. Ils portent chacun 20 pouces de haut sur 3 pieds 2 pouces de large.” According to an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Bibliothèque nationale, the pendants sold for 50 livres 10 sols to “Erbien,” a Swedish medalist.

The paintings do not appear in subsequent eighteenth-century sales.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 32.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 61.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 22.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 160.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 66.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 17.Ferré, Watteau (1972), 3: cat. B57.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 107.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 151, 160.

Eidelberg, “Dans ses lieux” (2001), 179-84.

REMARKS

In his "Notes manuscrites," Mariette commented that in this picture and its pendant, La Chasse aux oiseaux, Watteau “paroît y avoir voulu imiter la manière de Forest.” The landscape painter Jean Forest (c. 1634-1712) was then considered to be the finest landscape painter that France had ever produced. Pierre Crozat, Watteau’s patron, owned eight paintings by Forest, including two into which Watteau inserted figures of his own invention (see Paysage de Forest avec figures de Watteau). The painter Charles Coypel owned not only Watteau’s two pendants of La Chasse aux oiseaux and Acis et Galathée but also fourteen landscapes by Forest, probably the result of his father’s friendship with Forest. Others in Watteau’s circle, such as Antoine de la Roque, the editor of the Mercure de France and Watteau’s first biographer, owned a Forest landscape. A tantalizing clue to Watteau’s link to Forest lies with Nicolas Claude Henin (1679-1763), conseilleur de Roi, maître et doyen de la Chambre des comptes de Paris, and maître d’hôtel ordinaire du Roi. Nicolas Claude Henin was an amateur painter and Forest’s only acknowledged student. Although we cannot specify the exact relationship, he must have been related to Nicolas Henin (1691-1724), one of Watteau’s closest friends. The Parisian art community was relatively small and often closely inter-related. However, except for examples like this, we generally lack the key to open its many secrets.

Most Watteau scholars have avoided discussing this painting, which is understandable since we know so little about it. We not only lack the painting and are deprived of a sense of its color, but there are no preparatory drawings or even comparable landscape paintings by Watteau to afford us some idea of its appearance. Mathey dated Acis et Galathée to 1707-08, i.e., the earliest years of Watteau’s career, Roland Michel proposed c. 1712, and Adhémar placed it still later, in 1716. Most have avoided the issue of assigning a date and perhaps wisely so. Yet the picture and Watteau’s interest in Jean Forest are worthy of greater attention.

Ferré, consistently erratic about the authenticity of Watteau’s compositions, quotes his colleague Saint-Paulien (a pseudonym assumed by Maurice-Yvan Sicard) as doubting this work. Disregarding the importance of Caylus' firsthand knowledge of Watteau’s art, Saint-Paulien claims that there is no proof that this painting and its pendant were by Watteau. Such objections are pointless.