- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

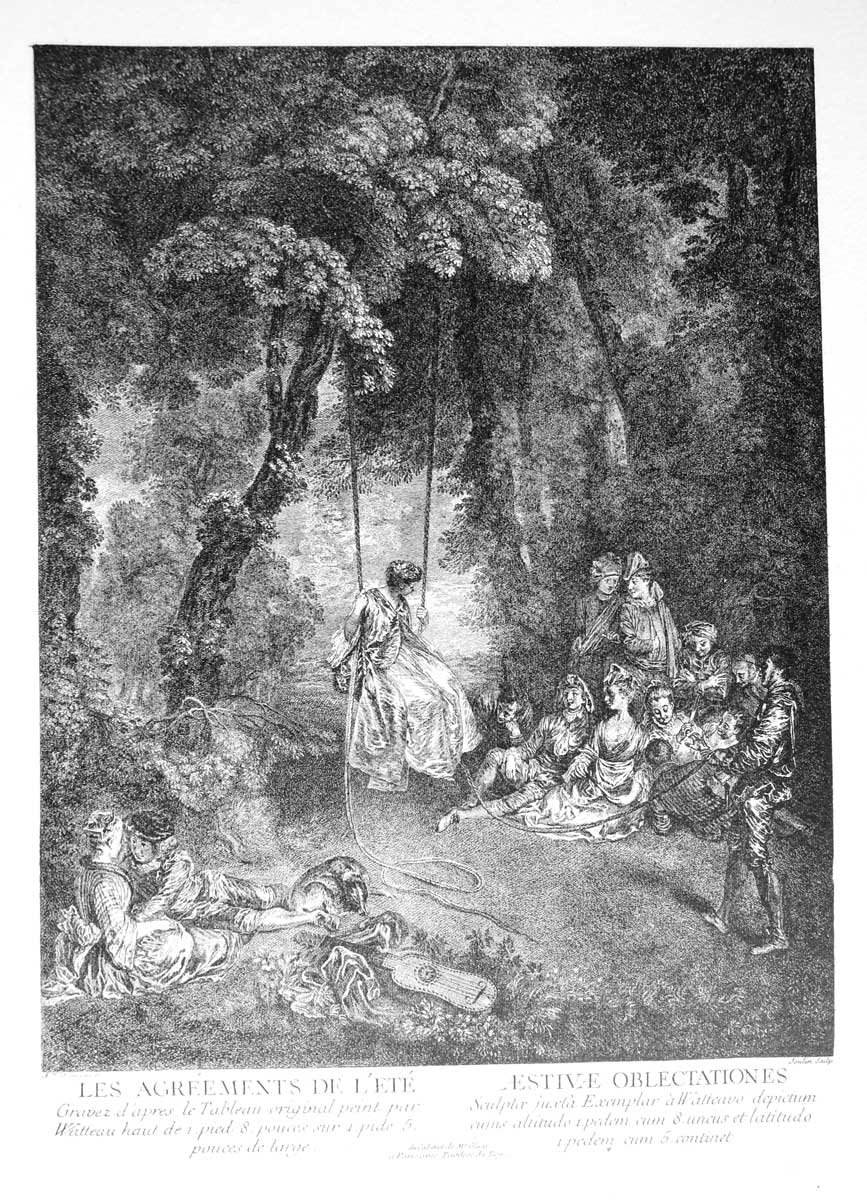

Les Agréments de l’été

Entered July 2014; revised February 2022

Presumed lost

Oil on canvas

54 x 45.9 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

L’Intérieur d’un parc

La Vue d’un parc

RELATED PRINTS

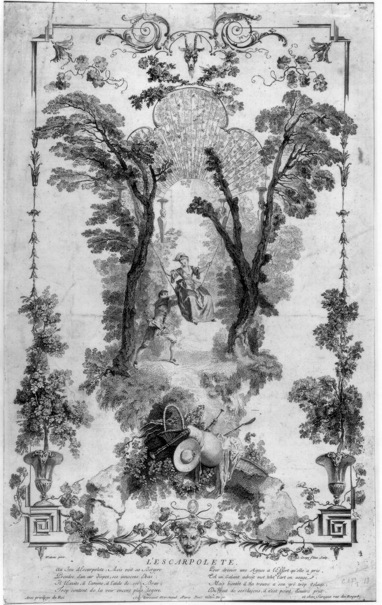

Watteau’s Agréments de l’été was engraved in reverse by François Joullain in 1732 for the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé. The print was announced for sale in the November 1732 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2449).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Claude Glucq (1676-1742). The caption on Joullain’s print proclaims that the painting was “du cabinet de Mr. Glucq.” There were two Glucq brothers interested in art: Jean-Baptiste Glucq and Claude Glucq (1674-1748). Both were cousins of Jean de Jullienne. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold proposed that the owner of Les Agréments de l’été was Claude Glucq because, as they claimed, the print described the owner as a member of parliament and this would apply to Claude alone. In fact, the print makes no such mention, but the announcement for its sale in the Mercure de France does: “Ce Tableau est dans le Cabinet de M. Glucq, Conseiller au Parlement.” Claude Glucq predeceased his older brother and apparently left his art collection to him.

Paris, collection of Jean-Baptiste Glucq, baron de Saint Port. The inventory after his death (prepared May 20–September 6, 1748; minutier Moisy), contains the following entry: “N°40. Un tableau de Vatteau, peint sur bois, représentant une Fête champêtre, dans sa bordure de bois sculpté doré, prisé cent cinquante livres.” The qualification “peint sur bois” appears to be in error.

Paris, collection of M. Vieuville (perhaps Etienne Auguste Baude, seigneur de la Vieuville et de Saint-Père, marquis de Châteauneuf). His sale, Paris, February 18ff, 1788, lot 107: “ANTOINE VATTEAU . . . L’intérieur d’un Parc, où l’on voit de grands arbres élevés & une femme sur une escarpolette, qu’un homme vêtu de rouge se dispose à faire aller, tandis que dix autres figures d’hommes & de femmes sont spectateurs, les uns couchés, les autres débout & assis; à droite & sur le devant, l’on voit un homme qui s’entretient avec une femme; près d’eux est un chien lévrier, un manteau & une guittare. Ce Tableau capital, est d’un effet séduisant & du beau faire de Vatteau. Hauteur 19 pouces & demi, largeur 16 pouces & demi. T.” According to the annotated copy of the auction catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, the painting was bought by the dealer Jean Baptiste Lebrun for 400 livres.

Paris, sale, December 9ff, 1788, collection of Anne Pierre, marquis de Montesquiou-Fezensac, lot 213: “PAR LE MÊME [ANTOINE WATTEAU] . . . La Vue d’un Parc, où l’on voit de grands arbres élevés & une femme sur une escarpolette, qu’un homme vêtu d’un ajustement rouge se dispose à faire aller, tandis que d’autres figures d’hommes & de femmes les regardent: l’on remarque sur le devant une conversation d’un homme & d’une femme; près d’eux est un lévrier, un manteau & une guitarre. Ce Tableau, d’un effet piquant, est d’une riche composition, & du beau faire de ce Maître. Hauteur 19 pouces, largeur 16 pouces. T.” The painting sold for 300 livres to François André Briant, a price 100 livres less than Lebrun had paid at the Vieuville sale. Although this was nominally the sale of the marquis de Montesquiou’s collection, it is doubtful that the marquis had actually owned the Watteau painting. It had been purchased only ten months earlier by Lebrun, and he probably slipped it into this sale, which he directed, to take advantage of a more prestigious-sounding provenance.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 116.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 117.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 100.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 3: cat. 102.

Dacier, La gravure de genre (1925), 58.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 125.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 246.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 2-W.

Posner, “Swinging Women” (1982), 97-98.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 266.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), 1: cat. 65, 121, 122, 131; 2: cat. 414, 487, 614; 3: R856, G125.

Valenciennes, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), 254-56.

Ziskin, Sheltering Art (2012), 108.

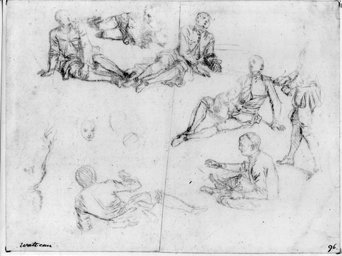

RELATED DRAWINGS

There are fourteen figures and a dog in Les Agréments de l’été, many of which can be traced to the artist’s drawings.

An early sheet of studies of a male model in different poses, mostly reclining on the ground, was used by Watteau for this composition. Although that sheet has not survived, it is recorded in a counterproof that Swedish count Carl Gustaf Tessin obtained from the artist in 1715 (Rosenberg and Prat 122). It and a number of other such counterproofs are now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Three of the seated men on the counterproof—the man at the top who rests his head on his hand, the man at the bottom of the sheet, seen from behind and gesticulating with an upraised arm, and the study at the right side of a man whose hand crosses and rests on his thigh—correspond to figures in Watteau’s painting, all close to each other. Also, the standing figure at the far right of the counterproof was transformed into the man manipulating the ropes of the swing. That Watteau employed all four studies from this one sheet demonstrates his economical means of working when transposing figures from his drawings to a painting.

When creating Les Agréments de l’été, Watteau turned to another early sheet, probably a nearby page in his album, with four studies of a seated woman. Again the original drawing is lost, but it is recorded in a counterproof that Count Tessin obtained from the artist in 1715 and that now is in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat 121). Watteau borrowed the figure of the seated woman with a fan in her hands for the woman in the painting who is seated on the ground. He modified the position of her hands slightly in the painting, but otherwise remained faithful to his original drawing.

Both the man reclining on the ground in the corner of the painting and the woman to whom he is paying court were derived from a third lost early drawing, one also known only through its counterproof in Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat 131). In the painting the man was given a beret and longer hair, and the woman was given a cap. Again we are reminded of Watteau’s economical way of taking several studies from a single sheet, and relying on sheets that were in close proximity to each other in his album.

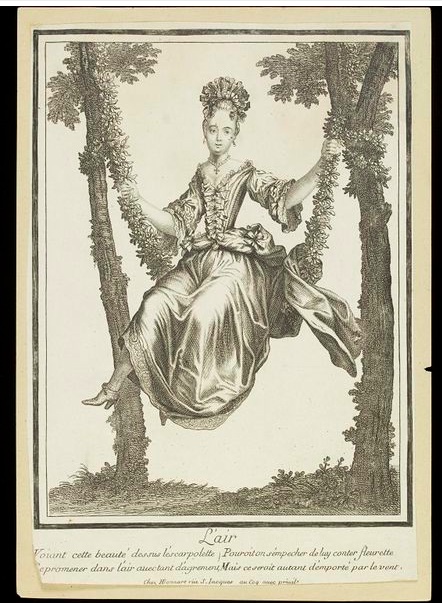

The preceding Stockholm counterproof also contains a remarkably vivacious study of a woman on a swing—a rare subject in Watteau’s drawings—and one might well wonder if Watteau did not first employ or plan to employ this or a similar study for his painting. Ultimately, he chose a quite different drawing showing a more mature, more sedately posed woman. That drawing is lost but is recorded in plate 340 of the Figures de différents caractères. As with some of the other drawings to be considered shortly, this lost drawing appears to have been executed well after the ones considered thus far.

It has not been previously noticed that the actor with turbaned head and arms crossed over his chest, one of the throng at the side of the painting, was taken from yet another lost Watteau study. That drawing is recorded in plate 305 of the Figures de différents caractères.

Watteau turned to other mature drawings for Les Agréments de l’été. From a sheet now in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 614), he borrowed two studies of hands, employing one for the woman holding a fan and another for the man gesticulating to her. In the latter instance it should be remembered that the basic lines of his body came from a much earlier study reflected in a Stockholm counterproof. The striking head of a man with a skullcap at the right of the Louvre drawing closely resembles the head of the man at the right of the engraving, but the cant of the head is slightly different; probably Watteau used a related drawing from this model.

Watteau also seems to have turned to another mature sheet for this painting, a drawing in the Louvre with five sensitive studies of a woman’s head (Rosenberg and Prat 414). The head at the bottom center was used for the woman seen at the far right of the engraving. Likewise, the head at the top center of the drawing, including the ruff around the neck, was utilized for the woman with a raised fan.

Finally, although Watteau’s drawing for the dog curled up at the feet of the courting man is not extant, it was copied by an anonymous draftsman (Rosenberg and Prat R856).

REMARKS

There is no record of the painting after the 1788 Montesquiou-Fezensac sale. Perhaps it fell victim to the French Revolution.

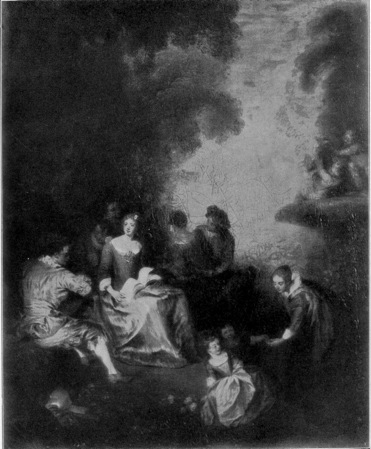

Despite the many preparatory drawings and Joullain’s engraving that states explicitly “A. Watteau pinxit,” Adhémar excluded Les Agréments de l’été from Watteau’s oeuvre. Her argument was based on two Pater paintings, one formerly in the Duke of Sutherland’s collection, and both entitled Les Agréments de l’été (Ingersoll-Smouse cat. 71bis and 71ter but with confused internal references). Adhémar argued that the two Pater paintings were “variants” of the composition engraved by Joullain and therefore the Joullain composition must be by Pater as well. Not only is this illogical reasoning, but, except for the common, essentially generic title that they share, the two Pater paintings are wholly unrelated to the composition engraved by Joullain. Adhemar’s senseless hypothesis must be disregarded. Nonetheless, Macchia and Montagni, taking their cue from Adhémar, also thought there was sufficient reason to reject the attribution of Les Agréments de l’été to Watteau. Modern scholars have rightly rejected Adhémar’s objection and have continued to include Les Agréments de l’été in Watteau’s oeuvre.

The dating of this painting is a rather complicated issue, especially without having the painting itself to study. While the Stockholm counterproofs date before 1715, the sheet in the Louvre with five heads of women has been dated to c. 1714 by Grasselli and c. 1715-16 by Rosenberg and Prat. The latter scholars have dated the drawing with the actor in a skullcap to c. 1718. Normally the painting has to postdate the latest of the drawings. However, there is a strong possibility that this work was created in two stages or, at least, that a painting from the early part of Watteau’s career was partially repainted some years later. As we have seen, a good number of the drawings used for Les Agréments de l’été are early studies, made before 1715. Yet other studies that Watteau employed—all for figures at what would have been the left side of the painting—are later. This distinct temporal division suggests that the painting was executed in two stages.

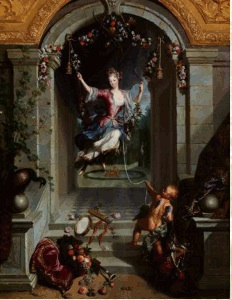

The motif of a woman on a swing has in recent years elicited much scholarly interest, often colored by an awareness of Fragonard’s erotically charged painting of 1767 now in the Wallace Collection. At the turn of the eighteenth century, women on swings appeared in popular prints such as those by Henri II Bonnart, and appeared in a more formal context in a decorative painting that Jacques van Schuppen exhibited in the 1704 Salon. The subject seems to have entered Watteau’s oeuvre in arabesques such as L’Escarpolette, known through an engraving by Louis Crepy fils. Then it appeared in paintings such as Le Plaisir pastoral, now in Chantilly. Of course, the frequent appearance of this theme in fêtes galantes by Watteau and his followers reflects the popularity of this entertainment in contemporary life, as well as the close relation between genre painting and reality.

Donald Posner proposed a provocative, highly sexual reading of Watteau’s images of women on swings, but his interpretation was highly personal. Apropos of Les Agréments de l’été, he claimed that because Watteau showed the man holding only one rope of the swing and left the other lying slack on the ground, and because the woman was looking to the “non-romantically engaged group” of men at the side, Watteau had intended “the obvious suggestion . . . that the girl wants two boys.” Such readings of Watteau’s paintings are neither “obvious” nor congruent with the artist’s biography or his art.

For copies of Les Agréments de l’été, CLICK HERE