- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

L’Alte

Entered August 2014; revised November 2022

Madrid, Museo del Prado, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Inv. 431 (1975.51).

Oil on canvas

32 x 42.5 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Alte d’infanterie

Le Bivouac

Bivacco

Das Biwak

Halt of an Army

La Halte

Halte des soldats

Soldiers, etc., at Rest

The Rest

The Rest Stop

RELATED PRINTS

The painting was engraved in reverse by Jean Moyreau before June 1730 when the engraving was announced for sale in the Mercure de France (pp. 1603-04). Moyreau disguised the oval format of the painting by extending the composition into a rectangle, and did the same for the pendant painting, Le Défillé.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). The engraving, issued in 1730, states: “Tirée du Cabinet de M.r de Jullienne.” The painting was sold by Jullienne prior to 1756 since it is not included in the illustrated manuscript catalogue of his collection made at that time and now in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

Paris, collection of Louis François de Bourbon, prince de Conti (1717-1776). His sale, Paris, April 8–June 6, 1777, lot 665: “Antoine Watteau . . . Une Alte d'infanterie: on y voit trois femmes, dont une Vivandiere. Une marche de Cavalerie & d'Infanterie. Ces deux tableaux qui sont d’un faire savant, sont peint sur toile, & portent chacun 13 pouces de haut, sur 16 pouces de large.” The painting sold for 665 livres to "Menajeau" according to an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie.

Paris, collection of Augustin Ménageot (1700-1784: painter and dealer). His sale, Paris, March 17ff, 1778, lot 107: “ANTOINE WATTEAU . . . Des Marches de Soldats & Vivandiers; deux sujets faisant pendans d’une très-bonne couleur, & touchés avec beaucoup d’esprit. Larg. 16 pouces. Haut. 13. T.” The pair sold for 920 livres to Dubois according to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Frick Art Reference Library.

Paris, collection of M. Dubois (dealer in silverware and jewelry). His sale, Paris, March 31-April 5, 1784, lot 78: “A. WATTEAU . . . Deux Tableaux faisant pendans; l’un orné de vingt-figures, représente une halte de soldats; l’autre est un défilé d’armée, composition de vingt-trois figures. Ces deux Tableaux viennent de la Collection de M. le Prince de Conti. Haut. 12 pouces, largeur 15 pouces. Ils sont gravés par Moyreau.” The two pendants were supposedly sold for 723 livres to Grenier according to the annotated copy of the catalogue in the Frick Art Reference Library, but this purported buyer was probably part of a fiction since the painting returned to Dubois’ collection and was put up at auction the following year.

Paris, sale, December 20ff, 1785, Dubois collection (presented anonymously), lot 79: “A. WATTEAU . . . Deux Tableaux faisant pendans, l’un orné de vingt figures, représente une halte de soldats; l’autre est un défilé d’armée, composition de vingt-trois figures. Ces deux Tableaux viennent de la collection de M. le Prince de Conty, & sont gravés par Moyreau. Hauteur 12 pouces, largeur 15 pouces.” Sold for 510 livres according to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Bibliothèque municipale, Versailles.

Paris, sale, March 27ff, 1787, collections of Sir John Lambert, M. du Porail, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun, et al., lot 185: “A. WATTEAU . . . Un beau Tableau riche de composition, représentant un repos & halte de soldats, avec d’autres figures sur le devant d’un paysage. Ce morceau piquant, & du plus fin de ce maître, est connu par l’estampe qu’en a gravé Moyreau. Hauteur 12 pouces, largeur 15 pouces. T.” Sold to Lebrun for 884 livres according to an annotated sale catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie. By this time L’Alte and its pendant had been separated from each other.About the time of the Revolution or shortly thereafter, L’Alte crossed the Channel to England. (This also was the fate of its previous pendant, Le Defilé.) Although there were a good number of military scenes in England attributed to Watteau and described as showing “An Encampment” or a “Scene in a Camp,” only a few were listed with the word “Halt.” One or more of these may be the painting under consideration:

London, Phillips, May 1-3, 1799, lot 149a (consigned by Hill), “Watteaux. Halt of soldiers,” sold for £2.17 to Horn.

London, Picture Repository, November 30ff, 1802, lot 98 (consigned by Meyer Solomon), “Watteau. A Halt of an Army.”London, Hermon, March 24, 1809, lot 63: “Watteau. The Halt of an Army,” sold for £10.10.

Petworth, Petworth House, collection of George O’Brien Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont (1751-1837). The date of acquisition is not known, but Earl Egremont possessed it by 1834 when he lent it to the winter exhibition of the Royal Society of British Artists. It remained with the Wyndham family by descent until 1930 when it was sold by Hugh, 4th Lord Leconfield, to Agnew. (Adhémar mistranscribed the family name as “Beaconfield,” an error repeated by Macchia and Montagni.)

London, Thomas Agnew and Sons, by 1929 (noted by Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs [1921-29], 1: 265); still with Agnew in 1933 (noted in a letter from Agnew to the Courtauld Institute on file at the Witt Library).New York, Wildenstein and Co., bought in 1943. Sold to Charles E. Dunlap in December 1946.

New York, collection of Charles E. Dunlap (1888-1966; coal industry executive) and Phyllis I. Dunlap (1902-1975). Her sale, New York, Parke Bernet, December 4, 1975, lot 380: “ANTOINE WATTEAU . . . A BIVOUAC (LA HALTE) 12½ x 16¾ inches / 32 x 42.5 cm

Note / Engraved in reverse by Jean Moyreau, 1729, as Alte, when in the collection of Jean de Jullienne. The picture and its companion piece, Le défilé, also engraved by Moyreau, remained together until after the Dubois sale. There is a drawing after the engraving by Delacroix.

Provenance / Jean de Jullienne, Paris, by 1729 / Prince de Conti, Paris, 8 April 1777, No. 665 (with pendant) / Menageot, Paris, 17 March 1778, No. 107 (with pendant) / Dubois, Paris, 31 March 1784, No. 78 (with pendant) / Anonymous sale, Paris, 20 March 1785, No. 79 (with pendant) / Chevalier Lambert sale, Paris, 27 March 1787, No. 185 / Earl of Egremont, Petworth House, by 1834 / Lord Leconfield, Petworth House / Agnew, London / Duveen, New York

Exhibition / London, Suffolk Street, 1834, No. 102

Literature / E. & J. de Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre d’Antoine Watteau, 1875, p. 58, No. 57 / Cf V. Josz, Antoine Watteau, 1903, p. 54 / C.H. Collins Baker, Catalogue of the Petworth Collection . . . in the possession of Lord Leconfield, 1920, No. 632 / E. Dacier, & A. Vuaflart, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIIIe siècle, 1922, vol. III, No. 222 (reproduction of Moyreau’s engraving) / L. Dimier, Les peintres français du XVIIIe siècle, vol. I, 1928, p. 33, No. 45 / W.R. Valentiner, Unknown Masterpieces, 1930, No. 1 / L. Réau, Les peintres français du XVIIIe siècle, 1928, No. 45 (reproduced pl. 26) / H. Adhémar, Watteau, 1950, No. 35 (reproduced pl. 16)

See color plate.”

Bought by Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza for $75,000.Lugano, collection of Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza (1921-2002; industrialist); transferred in 1992 to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in the Museo del Prado, Madrid

EXHIBITIONS

London, Royal Society of British Artists, Winter Exhibition (1834), cat. 102 (as by Watteau, lent by the Earl of Egremont).

New York, Wildenstein, Masterpieces (1951), cat. 16 (as by Watteau, Halt of an Army, lent by Charles E. Dunlap).New Orleans, Delgado Museum, French Painting (1953), cat. 26 (as by Watteau, Halt of an Army, lent by Charles E. Dunlap).

Washington, Collection Thyssen-Bornemisza (1979), cat. 50 (as by Watteau, La Halte, lent by Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza).

Washington, Paris, and Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P5 (as by Watteau, The Halt [“Alte”], lent by the Collection Thyssen-Bornemisza).

Ekserdjian, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection (1988), cat. 51 (as by Watteau, La Halte, lent by the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 57.

Baker, Petworth Collection (1920), cat. 632.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 54, 265; 3: cat 222.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 45.

Valentiner, Das Unbekannte Meisterwerk (1930), U.M. 76.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 35.

Cailleux, “Four Studies of Soldiers” (1959), iv, vi.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 40.Ferré, Watteau (1972), 1: 84, 208; 2: 465-66; 3: cat. B2; 4: 1097, 1104, 1128 (321).

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 79.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 167, 170, 273.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 34.

Lugano, Thyssen-Bornemisza, Catalogue (1986), cat. 325b

Jollet, Watteau (1994), pl. 14.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 58, 67, 68,

104, 179, 180, G48.Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 10.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 87.

RELATED DRAWINGS

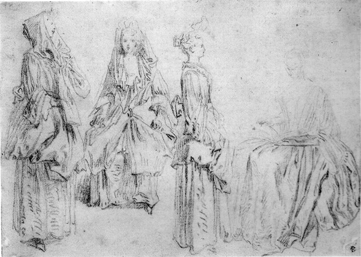

As in the case of many of Watteau’s military paintings, a good number of his studies from models were employed for this painting. Four extant sheets of such figure studies provided eight characters for the painting and he used them in a most economical manner.

One of the pertinent sheets (Rosenberg and Prat 58) shows a soldier seated in two different positions, and both were selected by Watteau for L'Alte. The man resting his head on his hand was put in the painting to the left side of the tree, and the angle of his inclined torso was gently adjusted to a more upright pose. The other figure, a man with his wounded arm in a sling, was placed farther to the right in the painting.

Likewise, Watteau utilized all four figures from a sheet in the École des beaux-arts, Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 67). Not only did he use all four figures for L’Alte but he took them in the same sequence, although with slight separations. The kneeling man at the far left of the drawing appears at the far left of the painting. Then, farther to the right in the painting, he added the seated soldier with a rifle under his arm. Beyond the man with a bandaged arm taken from the previous drawing, he returned to the Paris drawing for the remaining two soldiers. Remarkably, although these studies were drawn essentially at random and without narrative content, Watteau laid them out meaningfully on the canvas, with an intuitive sense of rhythm and cadence.

The fancily dressed woman at the left side of the painting, replete with a lace fontange in her hair, is based on the central study on a sheet in Indianapolis (Rosenberg and Prat 68).

The equally fashionable woman standing at the left of the painting, her back turned to us in a typical Watteau posture, is based on a study in the Musée Carnavalet (Rosenberg and Prat 104). The way in which the women are juxtaposed in the painting suggests that they are in conversation but not in an animated way. Women such as these appear in several of the artist’s military paintings, and although they may register something of the reality of camp life, their genteel elegance seems out of place in the rough environment of soldiering.

An intriguing puzzle associated with the L’Alte is the engraving by Benoît Audran for plate 125 of the Figures de différents caractères. It contains the standing officer and woman seen at the left side of Watteau’s picture, but in reverse. How should the engraved image be understood? Did Audran copy a Watteau drawing where the artist had redrawn the woman from the Carnavalet sheet and then add her male companion? Knowing what we do of Watteau’s working method, that would be anomalous. Rosenberg and Prat (cat. G48) proposed that the engraving was a record “not of a lost drawing but a detail from L’Alte.” There is absolutely no evidence that the engravers of the Figures de différents caractères ever copied details from Watteau’s paintings to make pseudo-drawings. Instead, I believe that Audran's engraving, like others in Jullienne’s corpus, reflects an oil counterproof. These are the rubbings that Watteau made after he painted the principal lines of the figures on the canvas, generally in a brown paint, and before he added the local colors. Watteau made at least one, perhaps two, counterproofs from the pendant painting, Le Défile, and these are recorded as plates 114 and 228 of the Figures de différents caractères.

REMARKS

Until 1975 L'Alte had not been seen firsthand by most critics. While it was still at Petworth in the first half of the twentieth century, most critics, including English ones, did not seek it out. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold were apparently unaware of its existence. The picture remained at a seemingly greater remove after World War II when it was in the United States. Although it was exhibited twice, the picture engendered little interest among Watteau scholars and, as a result, most were wary of accepting its authenticity. Adhémar, who knew the picture only from a photograph, noted its overpainted surface and was suspicious. Her opinion was followed by Macchia and Montagni. After its purchase by Thyssen-Bornemisza and its subsequent cleaning, which removed the overpainting and revealed the original oval format, critics freely accepted the Thyssen-Bornemisza picture as authentic.

In her account of the painting’s provenance, Adhémar introduced the idea that Lord Duveen was the owner of the painting after Agnew and referred the reader to Valentiner’s 1930 publication. However, in that book Valentiner lists the picture as being with Agnew and makes no reference whatsoever to Duveen. In truth, there is no indication that Duveen ever owned the painting. Nonetheless, Macchia and Montagni repeated Adhémar’s account, as did Alan Rosenbaum in his text for the 1979-81 exhibition of the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection. So too, Pierre Rosenberg cited Duveen’s ownership in the 1984 Watteau tercentenary exhibition catalogue and, even more specifically, he stipulated that Duveen obtained it in 1945. However, this cannot be true, since Duveen had already died in 1939. As forceful as that dealer was, even he could not have managed to buy the painting six years after his death. A mounted photograph at the Witt Library bears the erroneous annotation “Agnew/ London, 1946,” as though they still owned it after the war. However, and this is the crucial fact, Wildenstein’s records indicate that they owned the picture from 1943 when they bought it from Agnew. Curiously, none of the postwar scholars have ever associated the picture with Wildenstein.

There is an overall consensus that L’Alte, like all Watteau’s military subjects, stems from the early part of his career. Most scholars thought that these paintings have clustered around the time Watteau temporarily returned to Valenciennes. Since it was wrongly believed that this trip took place in 1709, the dating of this and the other military pictures have clustered around 1909-10. In 1981, for example, Roland Michel dated the painting to c. 1709. Rosenberg (1984) suggested a date of 1709-10 and proposed that the fontange headdress worn by the seated woman confirmed this idea. In a contrary way, Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold had thought that the fontange implied a date of 1712. Adhémar situated L'Alte in 1710. Posner assigned all the military paintings to 1709-14, writing that there could be no precision in dating them. The recent discovery that Watteau did not leave for Valenciennes until 1710 mandates a later date for both his drawings of soldiers and his paintings with military themes. This holds especially true for L’Alte, which has a more mature quality than most other pictures in this group. Glorieux has proposed that L'Alte was painted at the end of 1710 or the beginning of 1711, and that together with Le Défilé and the so-called Porte de Valenciennes they formed a series of oval paintings that originally were inserted in the boiserie of a small room.

For copies of L’Alte, CLICK HERE