- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

L’Amour mal-accompagné

Entered March 2015; revised January 2022

Presumed lost

Materials unknown

Approximately 61 x 87.6 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

An Allegory of Erotic Malice

Un Concert

Cupid in Bad Company

RELATED PRINTS

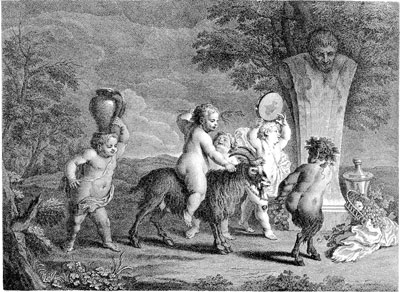

Pierre Dupin after Watteau, L’Amour mal-accompagné, engraving, prior to 1744.

The picture was engraved by Pierre Dupin (c. 1690-1751) prior to 1744.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Louis Quentin de Lorangère (d. 1743; greffier des presentations au Châtelet de Paris, receveur de la signature en chef du Châtelet de Paris). His ownership is announced on the Dupin engraving: “Tiré du Cabinet de Mr de Lorangère.” His sale, Paris, March 2ff, 1744, possibly lot 8: “Un jeu d’enfans; original de Watteau, de 2 pieds 2 pouces ¾ de large, sur un pied 2 pouces ½ de haut.”

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 116.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 118.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 34.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-28), cat. 272.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 15.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 112

Panofsky, “Gilles or Pierrot?” (1952), 334.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1957), cat. 333, 334, 954.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 66.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 75.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 1: 93; 2: 541; cat. B92.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 151.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 428, 429, R314.

REMARKS

Dupuis engraved L’Amour mal accompagné and Les Enfants de Sylène as pendants, and both were described as being in the collection of Quentin de Lorangère. Yet when Lorangère’s collection was sold on March 2ff, 1744, only one of the pictures was listed, although it is not evident which one. Lot 8—the only lot that could be assigned to either of these pictures –is frustratingly vague: “Un jeu d’enfans.” This is a description that could easily apply to either painting. Most scholars, unaware of this problem, have written as though the two pendants had appeared here together. It might have been sloppiness on the part of the cataloguer, who should have written “Deux jeux d’enfans,” or perhaps one of the paintings had been damaged or given away. We cannot tell. Curiously, neither painting was ever seen again.

The intent of this painting is unclear. At the side is a pedestal with a bust of a female satyr, perhaps implying the general nature or tone for this composition. Around this cult statue are three monkeys, one decorating the bust with a garland, one playing a bagpipe, and a third monkey costumed as Pierrot. The theme of music is extended by the presence of a violin and a musical score at the bagpipe player’s feet, and this probably explains the title “Un Concert” that was applied to the composition when it was sold in 1744. The meaning of this satiric allegory is all the more obscure because of its juxtaposition with a seemingly unrelated scene of five putti and a goat. A putto restrains the goat by holding one of its horns, another assists a putto who has fallen under the goat’s hooves, while a third seems to be beating the goat with a branch.

Accompanying Dupin's engraving is an eight-line poem:

Par ces Singes remplis de ruse & d’artifice

On peux sans doute, Amour, designer ta malice:

Ce Bouc sert de symbole à ta lascive ardeur;

Et de tels attributes ne te font point d’honneur.Que ne peut-on plutsost marquer ton caractére,

Par ta simplicité, par l’aimable candeur,

Par un attachement délicat et sincere!

Alors je seroist pres à te livrer mon coeur.

Translated, it reads in English:

By these monkeys full of guile and cunning,

Cupid, you can without a doubt point out mischievousness.

This goat serves as a symbol of your lustful passion,

And such attributes do you no honor.Instead, can we not characterize your nature,

By your simplicity, your lovable naiveté,

By your refined and sincere affection?

Thus I will be ready to give you my heart.

What does Watteau’s composition signify in its totality? The poem beneath the engraving speaks of the monkeys as “remplis de ruse et d’artifice” and the implications of love and maliciousness, while the goat is presented as an emblem of lascivious ardor. However, the poems under the Jullienne engravings often express contemporary poetic clichés without revealing anything about Watteau’s intentions. Dora Panofsky, whose interpretations of Watteau’s works suffer from the Romantic tradition of emphasizing the artist’s melancholia, proposed that the monkey dressed as Pierrot referred to the painter, traditionally considered the “ape of nature.” She saw this figure as standing apart physically and emotionally from the monkey playing a bagpipe, supposedly an erotic symbol, and thus representing the pathetic isolation of the painter from pleasure. Such involved interpretations seem far removed from early eighteenth-century modes and especially distant from Watteau. If anything, this painting and its pendant emphasize pleasure and humor, even frivolity. Bacchic in nature, they suggest inebriation and physical love as well as the folly that often surrounds them.

These words are not Watteau’s, of course, but belong to the poet hired by Jullienne. Although the lines may not allow us to enter Watteau’s mind, they suggest how his contemporaries thought.

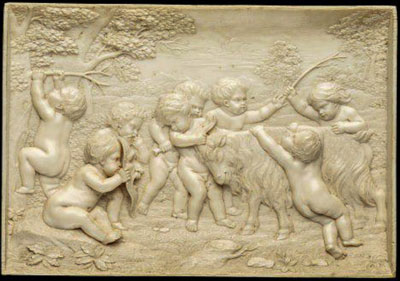

Parker and Mathey proposed that L’Amour mal accompagné was inspired by a relief by François Duquesnoy (1594-1643), known through versions such as the ivory one in the Victoria and Albert Museum. They published a drawing after Duquesnoy’s composition that they attributed to Watteau, and suggested that this drawing was used for his painting. However, Rosenberg and Prat rejected the attribution of the drawing to Watteau. Even if Watteau had known Duquesnoy’s composition (certainly Chardin did), the compositional similarities are not that close.

Jacques Sarazin, Putti with a Goat, 1640, marble, 90 x 66 x 75 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

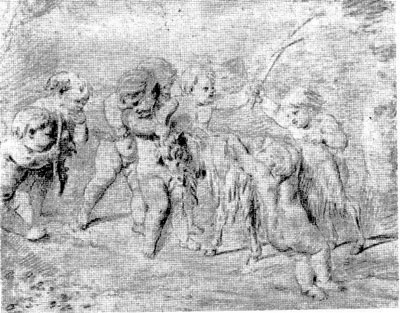

Watteau, A Seated Woman and Studies after Jacques Sarazin’s Sculpture of Putti with a Goat (detail), red and white chalk, 22.2 x 37.6 cm. London, British Museum.

Pierre Dupin after Watteau, L’Amour mal-accompagné (detail), engraving.

The playful theme in L’Amour mal-accompagné’s of putti cavorting around a goat more closely follows a famous sculptural group by Jacques Sarazin (1588/90-1660). There, as in Watteau’s rendering, one putto steadies himself by holding the goat's horn, while a second putto has fallen in front of the animal. There were several versions of this composition. The most famous is the marble group that was at Versailles in Watteau’s lifetime and is now in the Louvre, but Watteau probably copied one of the versions in a Parisian private collection. A terracotta modello was in Coypel’s collection and a bronzed terra cotta version was in La Live de Jully’s collection. A larger version with five putti (the same number as in L’Amour mal accompagné) was owned by Jean de Jullienne. Two Watteau studies after Sarazin’s sculptural group are extant, one whose present whereabouts are untraced, the other in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 428 and 429). But Watteau must have made still other studies after the sculpture since alternative views of it are reflected in his paintings, including Amusements champêtres, La Famille, La Cascade, and Récreation galante. In these four paintings, the sculpture is shown as a three-dimensional group and more closely follows Sarazin’s invention. Here, the figures are presented as a frieze and the relationship to Sarazin is less literal. Not surprisingly, when discussing Watteau’s drawings after this sculpture neither Parker and Mathey nor Rosenberg and Prat associated them with L’Amour mal accompagné.

These and other sculptures by Sarazin and Duquesnoy, as well as so many paintings by Poussin, remind us of the great popularity of such infant subjects. Indeed, although often overlooked, they constitute a significant category in French art that continued on in the eighteenth century, as is witnessed by many paintings by Boucher and Fragonard. Although Watteau is often portrayed as an outsider, here again he shows himself immersed in the central currents of French tradition.

A wide range of dates has been proposed for L’Amour mal-accompagné. Mathey placed it among Watteau’s earliest works, c. 1704-05, which is consistent with his desire to date most of the artist’s subjects with putti to those early years, but it is a weak idea. Ferré quotes Saint-Paulien as placing the painting during the time when Watteau was in Audran’s atelier, presumably meaning c. 1709-1710. However, Watteau’s reliance on Sarazin’s sculture suggests that it must date no earlier than 1715, when he was in contact with Crozat and Vleughels, and had access to such works of art. Adhémar considered it a mature work from 1716. Rosenberg and Prat dated Watteau’s drawings of the Sarazin group to c. 1715, thus indicating a probable terminus post quem for the painting. Unfortunately Dupin’s engraving does not help because he was a graphic artist of limited talent. As is shown by his engravings after other Watteau compositions (e.g., La Danse champêtre, Le Départ pour les isles, and Les Enfants de Sylène), he could not capture the quality of Watteau’s art, and so any judgment based on Dupin’s images is problematic.