- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

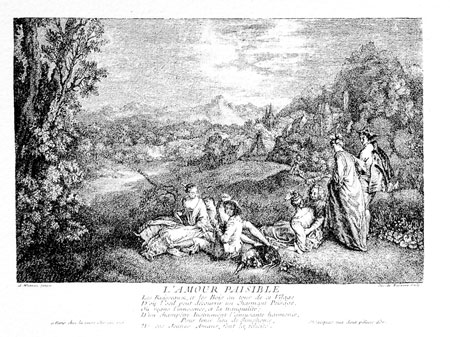

L’Amour paisible

Entered March 2015; revised March 2024

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, GK I 5337.

Oil on canvas

56 x 81 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

L’Amour à la campagne

Die Liebe auf dem Lande

Peaceful Love

Tranquil Love

RELATED PRINTS

The painting was engraved in reverse by Jacques de Favannes prior to June 7, 1730, when Geneviève Marguerite Chéreau, widow of François II Chéreau, was granted a copyright for this print.

PROVENANCE

The owner of the painting is not indicated on the engraving nor was it announced when the print was released. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold suggested that it might have been with Jullienne.

The picture was bought, presumably in Paris, by one of Frederick the Great’s agents. Its early presence in the Prussian collection is not clear, but Rosenberg has suggested that it may have been a picture in the Small Gallery of the New Palace, listed in the inventory drawn up in 1773 by Osterreich as “agréable conversation dans une agréable contrée, peinte sur toile de Watteau. Cette pièce a été grave à Paris.” The various changes in its whereabouts as it was moved from the Berlin palace to Potsdam and back are charted in Vogtherr, Französischer Gemälde (2011), 152.

EXHIBITIONS

Berlin, “Die Franzosische Schule des XVIII. Jahrhunderts” (1883), cat. 45.

Paris, Exposition universelle, Frédéric le Grand (1900), cat. 29 (as by Watteau, L’Amour à la campagne [L’Amour paisible]).

Berlin, Königliche Akademie, Werken französicher Kunst (1910), cat. 68 (as by Watteau, Die Liebe auf dem Lande, Seiner Majestät des Kaisers und Königs).

Paris, Palais national, Chefs-d’oeuvre (1937), cat. 235 (as by Watteau, L'Amour paisible, lent by the Palais Neuf, Potsdam).

Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, Malerei des 18. Jahrhunderts (1947), cat. 116 (as by Watteau, Die Liebe auf dem Lande, lent by the Verwaltung der Schlösser und Gärten).

Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, Französiche Kunst (1951), cat. 57 (as by Watteau, L’Amour paisible, lent by the Verwaltung der Schlösser und Gärten).

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Meisterwerke (1962), cat. 97 (as by Watteau, Liebe auf dem Lande).

Paris, Louvre, Peinture française (1963), cat. 37.

Frankfurt, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Einschiffung nach Cythera (1982), cat. D18 (as by Watteau, L’Amour paisible, Die Liebe auf dem Lande, lent by Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg).

Washington, Paris, and Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P66 (as by Watteau, Peaceful Love [L’Amour paisible], lent by Schloss Charlottenburg, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, Berlin).

Ottawa, National Gallery, Age of Watteau (2003), cat. 8 (as by Watteau, Peaceful Love, lent by the Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 103.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), pl. 66.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 74.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 161.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 34.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 207.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 174-77.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 174.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 116, 147-48, 243, 295, cat. A31.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 99, 160, 223.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 9, 14-15, 111, 173, 188.

Eidelberg, “Watteau’s Italian Reveries” (1995), 127-28.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 96, cat. 86.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 211-13.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. 5.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Drawings for almost all of the seven figures in this composition are known.

Watteau, L’Amour paisible (detail).

Watteau, Studies of a Standing Man with a Cape (detail), red and black chalk. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

Watteau, Two Studies of a Standing Woman, red, white, and black chalk, 29.9 x 20.2 cm. Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett.

Watteau used two separate sheets to construct the couple standing at the left side of the painting. The man was taken from the rightmost figure on a celebrated sheet in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 504). The woman was taken from a remarkably strong drawing in Berlin where she appears both full length and in a more detailed study of her head (Rosenberg and Prat 478).

Watteau, L’Amour paisible (detail).

Watteau, Studies of a Woman Seen from Behind, and Various Hands (detail), red, black, and white chalk. Private collection.

Watteau, Studies of a Man (detail), red chalk. Geneva, private collection.

The woman reclining on the ground, her back turned to us, was based on a Watteau drawing in a private Parisian collection (Rosenberg and Prat 526), while the man who grasps her waist was taken from a drawing now in a Geneva collection (Rosenberg and Prat 506). For the man, Watteau relied on the central study on the page for the head, but used a separate study at the left for the position of his extended arm.

Watteau, L’Amour paisible (detail).

(?) Watteau, Study of a Guitarist Seated on the Ground, red chalk, gray wash, 7.6 x 10.1 cm. Washington, National Gallery of Art.

Watteau, Study of a Woman Seated on the Ground, red, black, and white chalk, 22.9 x 22.8 cm. Rotterdam, Boijmans-Van Beuningen Museum.

The group reclining on the ground at the right of the painting is also a composite of otherwise unrelated studies. The source of the young guitarist is problematic. A drawing in the National Gallery of Art, Washington (Rosenberg and Prat R839), would seem to be the immediate source, but its attribution has been challenged by Rosenberg and Prat. The drawing is fairly dry and dispirited, and the use of gray wash is a cautionary sign. Yet the atmospheric rendering of trees on the verso of the sheet is quite seductive. Rather than being just a copy after the painting as Rosenberg and Prat have claimed, its graphism suggests that it must at least be a copy after Watteau’s original drawing, if not the original study itself. The woman holding a fan was taken from a drawing now in the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 492).

The drawing Watteau employed for the reclining man at the center of the composition is not known to have survived. Also missing is the drawing that Watteau would have relied on for the dog. However, a monochromatic oil “drawing” of this dog is in a Parisian private collection. It was once in the so-called Groult Album, an album that contains drawings by Pater for the greater part. This sheet is not an oil counterproof but, rather, a painted sketch. Its attribution is moot.

One of the fascinating aspects of L’Amour paisible are the oil counterproofs that are associated with it. These were made by pressing paper over the surface of the canvas after the primary aspects of the figures had been drawn in chalk and reinforced with a brush and brown oil paint. Because these oil counterproofs constitute an unusual genre and because they are halfway between drawing and painting—neither the one nor the other—specialists in both fields tend to overlook them. Yet they prove to be a crucial aspect of Watteau’s creative process.

Watteau, Standing Couple, oil counterproof, 24.2 x 16.2 cm. London, British Museum.

Watteau, L’Amour paisible (detail).

The first example is an oil counterproof in the British Museum showing the couple standing at the left side of the painting. As is always the case for any counterproof, it reverses the figures in the original drawings and the painting. Also evident is the remarkable fidelity and skill with which Watteau transcribed his drawings into paint.

Watteau, Woman Seated on the Ground, oil counterproof, 11.7 x 13.5 cm. Cambridge, The Fitzwillam Museum.

Watteau, L’Amour paisible (detail).

The second oil counterproof is in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. This too conveys not only the major lines of the figure but also some sense of the fluency with which Watteau brushed it onto the canvas. Unlike the Berlin painting, here the woman is not embraced by a male suitor. The significance of this will be discussed later.

A third oil counterproof related to L’Amour paisible was recorded by François Boucher as plate 178 of the Figures de différents caractères. The lost counterproof showed the figures in the opposite sense of the painting but, in turn, the engraving reverses the direction of the counterproof. As a result, the engraving and the painting show the figures in the same direction, which is visually convenient for making a comparison but misleading. The lost counterproof evidently included a tree trunk between the couple, whereas a second man fills that space in the Berlin painting.

The engraving attracted little attention until a half century ago when I proposed that it was not after a lost compositional drawing but was, instead, after a lost oil counterproof. Rosenberg and Prat bypassed this idea in their catalogue of Watteau’s drawings. Instead, they proposed a very different explanation, namely that Boucher was directly copying the figures in the Berlin painting. Although these pursued a similar train of thought in explaining other problematic engravings in the Figures de différents caractères (as discussed in our entry for L’Amour au théâtre italien), there is little justification for such assumptions. Rather, as I have shown previously, there are several instances of engravings in the Figures de différent caractères that were made after oil counterproofs, ones associated with figures in Watteau’s L’Aventurière, L’Assemblée dans un parc, and Le Défilé. Most recently, Vogtherr has concurred that the Boucher engraving is after an oil counterproof.

That there are at least three oil counterproofs associated with L’Amour paisible is remarkable but even more remarkable is the recent revelation by Vogtherr that the counterproofs were not pulled from the Berlin painting. A close examination of the Cambridge counterproof reveals that its thread count is different from that of the Berlin canvas. The inescapable conclusion is that the counterproofs were made from a different, earlier painting that shared some of the same figures. The lost painting probably was not identical to the Berlin painting, especially since when Watteau painted two or more versions of the same composition, he introduced minor and major changes. (Consider the several variations on his early Les Jaloux, the two versions of the Pélerinage à l’île de Cythère and the Wallace Collection’s Divertissements champêtres.) Indeed, this would explain why the Cambridge counterproof shows the seated woman alone on the ground without a male companion embracing her. This would also explain why Boucher’s engraving shows a seated couple separated by a tree rather than the third person seen in the Berlin painting.

What do these oil counterproofs reveal about Watteau’s studio practice? It would seem that he consulted the sheet in the British Museum when creating L’Amour paisible since the Berlin painting mimics the conjoining of the two figures just as seen in the counterproof. A similar conclusion can be reached apropos of the couple seated on the ground; their juxtaposition is the same in Boucher’s engraving and the Berlin painting. Or did Watteau employ both his drawings and his oil counterproofs when working up his painting? Moreover, in the course of executing the painting, Watteau changed many of the details. For example, the woman seated at the left has a ribbon in her hair.

Whereas he is often characterized as a free if not undisciplined artist, haphazardly leafing through his drawings and pulling a figure from one page, another figure from a different sheet, a head from still a third, and miraculously bringing them together, these counterproofs show that the artist also had a more disciplined, orderly side. His character and his working method were more complex than we perhaps had realized.

REMARKS

Because Jullienne assigned the same title to this painting and a fête galante owned by Dr. Mead, occasional slips have crept into the literature. Roland Michel, for example, claimed that Dr. Mead owned the painting now in Berlin.

Although there is general agreement that the Berlin L’Amour paisible is an outstanding work of Watteau’s maturity, there is only a vague consensus as to when he exectued this picture. Mathey proposed 1716; Macchia and Montagna preferred 1717; Roland Michel, Rosenberg, and Temperini thought 1718; Börsch Supan and Glorieux suggested 1718-19; and Adhémar claimed 1719.

The drawings used for this painting have been placed in this time frame as well. Although rarely agreeing on the same exact year, Grasselli as well as Rosenberg and Prat have suggested c. 1716-17 for most of the drawings discussed here. This accords with the general range of dates proposed for the picture.

A small but telling aspect of the landscape in L’Amour paisible is the castle perched on the hill at the left side of the painting. The buildings are almost identical to those seen in the Louvre Pèlerinage, presented to the Académie royale in 1717—one of the few fixed dates in Watteau’s chronology. As I have suggested previously, both sets of buildings may have been based on one of Watteau’s many drawings after Titian and Campagnola. They typify the way in which the artist incorporated Venetian motifs into his landscapes in the latter part of his career.

For copies of L’Amour paisible, CLICK HERE