- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin

Entered May 2015; revised May 2021

Waddesdon, Waddesdon Manor, inv. 2374.

Oil on panel

18.6 x 23.8 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Harlequin, Pierrot and Scapin

A Masquerade

Pierrot, Harlequin and Scapin

RELATED PRINTS

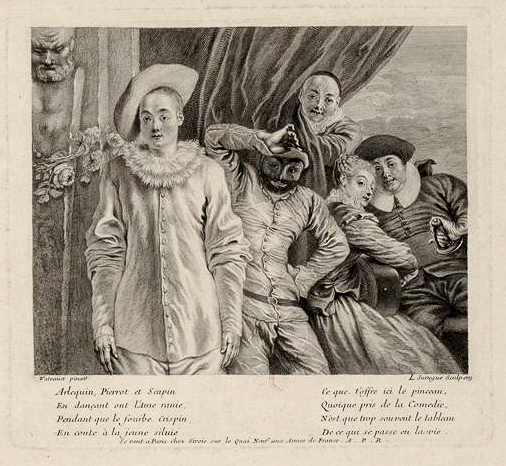

Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin as well as its pendant, Pour nous prouver que cette belle, were engraved in 1719 by Louis Surugue in the same direction as the paintings. Surugue’s name and the date 1719 appear on both of the prints, as does the address of Pierre Sirois, the art dealer to whom Watteau sold some of his first paintings. These two prints are of great interest because they are among the few undertaken in Watteau’s lifetime, and presumably with his awareness and approval. The 1719 date is very useful as a terminus ante quem for the paintings, one of the few fixed markers in the chronology of his oeuvre.

Jacob Wangner after Surugue, Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin, engraving.

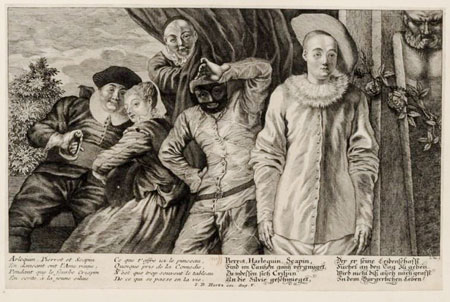

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold cite six French and German copies after Surugue’s print, some in reverse, some with modified dimensions such as the version by Jacob Wangner (1705-1781) with an extended width. One even has an octagonal format.

Anonymous French artist after Louis Surugue, Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin, engraving.

There prove to be other prints as well, such as this anonymous example in the collection of Ralph de Butler. It is a copy after the Surugue print, and although it retains the title of the painting, it omits Watteau’s name. The text of the first quatrain is barely visible at the left, while that of the second quatrain is readily apparent at the right.

PROVENANCE

London, collection of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792; painter and president of the Royal Academy). His sale, London, Christie’s, March 11-14, 1795, lot 83: “Watteau . . . A pair, A MASQUERADE AND A MUSICAL CONVERSATION, beautifully painted. The colouring exhibiting the brilliancy of the Venetian school; the pencilling is light, and admirably adapted to the subjects.” Bought for £19.19 by Michael Bryan according to the Getty Provenance Index and the annotated copy in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie. The pendant was Pour nous prouver que cette belle, now in the Wallace Collection.

London, sale, Bryan’s Gallery, April 27ff, 1795, the collections of M. de Calonne, Baron Nagel, and Sir Joshua Reynolds, lot 44 (specified as coming from Reynolds’ collection): “Watteau . . . A pair, a Masquerade, and a Musical Conversation—very beautifully painted.”

London, Collection of Edward Coxe. His sale, London, April 23, 1807, lot 8: “DITTO [WATTEAU] . . . A Masquerade, the Companion—both undoubted Specimens, and from the Collection of SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS.” The previous lot was “A Concert,” i.e., Pour nous prouver que cette belle. The pair was sold for 19 guineas according to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. The auction was run by Peter Coxe.

Collection of John Proby, 1st Earl of Carysfort (1751–1828). His sale, London, Christie’s, June 14, 1828, lot 29: “Watteau . . . A pair, small. A Masquerade and Musical conversation.” Bought by Henry Rogers for £63. The annotated copy of the catalogue at the National Art Library, London, shows the paintings as having been bought by “Rogers.”

London, collection of Henry Rogers (1774-1832). Until now the buyer at the Carysfort sale has been identified as Samuel Rogers, Henry’s older brother. This was a reasonable assumption since Samuel Rogers was the recorded owner of the painting in 1856. However, it was first in Henry’s collection, since Henry lent it to the British Institution's exhibit in 1829, just a year after it was bought at the Carysfort sale. On Henry’s death in 1832 it must have passed to his older brother Samuel, who survived him by two decades.

London, collection of Samuel Rogers (1763-1855; poet). His sale, London, April 28ff, 1856, lot 566: “A masquerade: a group of five figures in masquerade dress. From the Earl of Carysfort's Collection.” The pendants were sold separately. A masquerade was bought for £162.15 by Bentley on behalf of Thomas Baring.

Frankfurt, collection of Baron Wilhelm Carl von Rothschild (1828-1901; banker and financier). This provenance comes from the Rothschild family and is otherwise undocumented. The painting was probably bought directly from the 1st Earl of Northbrook, just as Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild bought a landscape by Cuyp from that earl.

Collection of Freifrau Mathilde von Rothschild (1832-1924), acquired c. 1889. By descent to Albert von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1879-1941); acquired in 1933 by Baroness Edmond de Rothschild (1853-1935); by descent to her son James de Rothschild (1878-1957); bequeathed to Waddesdon Manor, The Rothschild Collection (The National Trust) in 1957.

EXHIBITIONS

London, British Institution, Exhibition (1829), cat. 35 (as Watteau, A Masquerade Scene, lent by Henry Rogers).

London, Royal Academy, Works by the Old Masters (1889), cat. 94 (as Watteau, Masquerade, lent by the Earl of Northbrook).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, Watteau (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 75.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 68, 262; 3: cat. 97.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 60.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), under cat. 163.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 69.

Brookner, “French Pictures at Waddesdon” (1959), 273.

Levey, “French and Italian Pictures” (1959), 57.

Waterhouse, Waddesdon Manor (1967), cat. 135.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 155.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B73.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 219.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 260, 273.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 254, 257-58, 290.

Grasselli in Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), under cat. D96.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 400, 496, 596, 602, 621, A1.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 254-55.

Vogtherr, Watteau at the Wallace Collection (2011), 97-102.

Plock, “Pierrot, Harlequin and Scapin” (2011).

RELATED DRAWINGS

Several figures in Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin are analogous to ones in other Watteau paintings. The Pierrot gazing at us directly, his arms awkwardly held to his sides, strikes a typical pose for this commedia dell’arte character. He appears in this pose in paintings such as Pour garder l’honneur d’une belle, Le Rêve de l’artiste, Les Habits sont italiens, Les Comédiens italiens, and the great Gilles in the Louvre, as well as in Watteau's early arabesque, Pierrot debout. In those works his hat is not set at a slant as here. Likewise, Harlequin, in his characteristically twisted posture, hand to his hat, appears in several paintings including Comédiens italiens and the arabesque Arlequin debout. So too, Scapin at the far right, his head in front of the curtain, functions compositionally like the one in Les Habits sont italiens. Despite the many drawings that study these theatrical figures, none can be linked directly to Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin.

The actress playing the guitar in Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin seems to have been based on a sheet of beautiful trois crayons studies in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 596). Unless he referred to another study made from the same model, Watteau must have used the leftmost figure on the Louvre sheet, but altered the angle of her head.

Crispin’s arm and his hand holding his sword hilt were first studied in a drawing now in the Rijksmuseum (Rosenberg and Prat 602). This area is merely a blur in the Waddesdon Manor picture for reasons to be discussed below, but as one can see in Surugue’s engraving, Watteau faithfully copied his drawing when executing the painting. There are other Watteau drawings of this actor in various poses, but the study for this painting depicting his torso and head has not survived.

REMARKS

There has been considerable confusion regarding the authenticity and provenance of the different versions of Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin. The two chief contenders have been the paintings at Waddesdon Manor and Althorp. Among those who favored the Althorp version were Zimmerman, Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, and Adhémar. Opposing them were de Goncourt, Réau, Brookner, Waterhouse, and Vogtherr, all of whom have favored the Waddesdon painting. Macchia and Montagni, Roland-Michel, and Posner thought that the original was lost. Temperini did not include the Waddesdon Manor painting, but inexplicably accepted the pendant in the Wallace Collection. Jean Lévy believed that neither the Waddesdon Manor nor the Althorp versions were by Watteau and preferred, instead, the painting in Moulins (letter of January 13, 1959, in the Waddesdon Manor archives).

The scientific analysis of the Waddesdon Manor painting in 2012 by Anna Sandén helps establish its primacy. The Waddesdon panel, like its pendant in the Wallace Collection, was enlarged on all four sides through the addition of narrow strips of wood; these measure approximately 2 cm at the left and right sides, and 1 cm at the top and bottom. These strips were then painted to extend the composition outward. However, they are quite crude additions. For example, the lower portion of Harlequin’s diamond-patterned costume was painted in conformity with the existing pattern, but its alternating yellow patches were not continued. Pierrot’s fingers are mangled. The garland of roses that hangs across the herm is only vaguely drawn; the one exception is the flower at the right, just above Pierrot’s shoulder, that is evidently all that remains of the original scheme. At the far left, Crispin’s hand and sword are just blurs of paint. Recognizing this loss of quality, Vogtherr attributed these outer portions to an artist other than Watteau himself.

Vogtherr believed that these strips were added before 1719 when Surugue executed his engraving, which shows these areas. However, the evidence points to a very different conclusion. First of all, Watteau was still alive in 1719 (albeit in London for the second half of the year), and he and Surugue had been allies in the past. Surely there must have been amicable relationship in this undertaking. As indicated, the painting on these added strips is not only inferior but also imprecise. The blur representing Crispin’s hand on his sword hilt, for example, would not have given Surugue sufficient information to engrave what he did, yet what Surugue engraved closely corresponds to Watteau’s drawing from the model. I would argue that Watteau’s painting originally contained the full composition that Surugue engraved, including the floral garland, Pierrot’s fingers, Harlequin’s pant legs, and Crispin’s hand on his sword—all the areas that Surugue engraved with faithful accuracy. Next, at some unspecified date Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin and its pendant were cut down. The date when this occurred cannot be specified, especially since there is no record of the painting’s measurements in the eighteenth- or nineteenth-century records. Then, prior to 1850 when the pendants were separated, they were restored to their original measurements; the additional wood strips were attached and were painted in general accordance with Surugue’s engraving. If this sequence seems strange, it should be remembered that exactly the same sequences of cutting down panels and later reconstructing the lost portions from the Jullienne engravings occurred with two other Watteau fêtes galantes, La Cascade and La Danse paysanne.

Reconstructing the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century provenance of the original painting has been complicated by the fact that both the Waddesdon Manor and Althorp versions have claimed some of the same early history, such as possession by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Moreover, other provenance has been erroneously claimed for Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin. The painting’s supposed appearance in the Champgrand sale of 1776 and the Devouge sales of 1784 proves to apply to a different version of the composition, Plusieurs personnes déguisées en habit de caractère. It's supposed presence at the Bohn sale in 1885 proves to refer to a wholly different composition, Les Habits sont italiens.

Watteau’s Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin was originally a pendant to Pour nous prouver que cette belle.

Both paintings feature five, three-quarter-length figures arranged close to the foreground. Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin contains commedia dell’arte characters, while its pendant has courtly figures making music. Whereas the background of Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin has a herm and curtain to close off the space, its pendant has nothing but open sky. Together, the two pictures are rather ill-conceived pendants in theme and composition, raising the question whether this is not another example of Watteau adding a second picture to one already finished. Posner took the issue to an extreme conclusion, contending that the two compositions never were pendants and that the two Surugue engravings were merely printed together. He overlooked the fact that the original pendants, as well as the Althorp versions, were hung together in the eighteenth century. Moreover, he voiced that opinion before the recent investigation of the panels’ physical construction. More recently, Michel also questioned whether the two paintings were pendants, but without giving reasons.

The caption under Surugue’s engraving is enlightening, mainly because it was composed during Watteau’s lifetime. Although Watteau was in England in the second half of 1719, there is no evidence that Surugue’s engraving was not made while Watteau was still in Paris. Michel, ever anxious to question, if not destabilize, what is known, argues that the engravings were executed while Watteau was in England and thus without Watteau’s knowledge or approval, forgetting that the artist and Sirois, the dealer identified on the prints, were allies. Even if Watteau had been in England when Surugue made his engraving, and I do not think this is so, the quatrains under the engraving are more significant than the texts under most of Jullienne’s engravings, which were executed after the painter’s death. The poem under Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin reads as follows:

| Arlequin, Pierrot & Scapin En dançant ont l’Ame ravie, Pendant que le fourbe Crispin En conte à la jeune silvie |

Harlequin, Pierrot, and Scapin Please their souls in dancing, While the deceitful Crispin Tells tales to the young Sylvia. |

| Ce que t’offre ici le pinceau Quoique pris de la Comedie, N’est que trop souvent le tableau De ce qui passe en la vie. |

What the brush offers you, Although inspired by the Comedy, All too often the painting depicts What happens in life. |

These two quatrains inform the viewer of the characters’ names (that the actress is called Sylvia is noteworthy because the costumes of the several actresses in the commedia dell'arte were never clearly defined), and they point out that the scenes in the commedia dell’arte mirror life itself, opposing the central trio of happy comedians to Crispin's telling deceitful tales to Sylvia at the right. Although the poem is little more than a pleasantry, it serves as a guide to those who would read more complex—often too complex—narratives into Watteau’s paintings.

For copies of Arlequin, Pierrot et Scapin CLICK HERE