- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

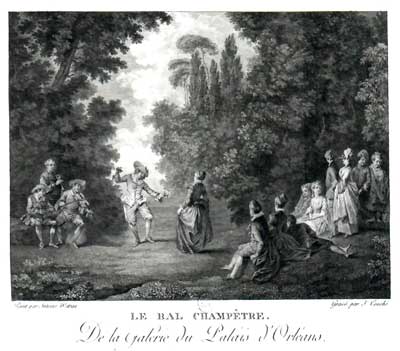

Le Bal champêtre

Entered January 2016, revised April 2021

Fontainebleau, private collection

Oil on canvas

96 x 128 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Le Bal

Un Bal

A Ball

The Country Ball

Un Couple dansant un menuet

Une Danse de village

Fête Champêtre

RELATED PRINTS

Jacques Couché after Watteau, Le Bal champêtre, engraving, c. 1800.

This composition was not engraved for Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé. Perhaps it was considered too similar to La Musette, which was included in the Jullienne corpus.

The painting was engraved at the end of the eighteenth century for the Galerie du Palais Royal, a compendium of engravings after paintings in the Orléans collection. Jacques Couché’s engraving was probably executed after a drawing made from the painting, as were many of the other engravings done for this publication and for which the preparatory drawings are in the Doucet Library, Paris. However, the drawing used for Le Bal champêtre seems not to have survived.

PROVENANCE

Paris, Palais Royal, collection of Louis d'Orléans, duc d’Orléans (1703-1752). According to Dezallier d’Argenville, Voyage pittoresque, the painting was hung in the “petite galerie” and was cited as “Une Danse de Village de Wateau” (in both the 1749 and 1752 editions). It is tempting to think that Louis d’Orléans might have inherited the painting from his father, Philippe d’Orléans (1674-1723), whom Watteau knew, but no documentation supports such a supposition.

Upon the death of Louis d’Orléans in 1752, the painting passed to his son, Louis Philippe, duc d’Orléans (1725-1785). Upon the death of Louis Philippe, the painting passed to his son Louis Philippe Joseph (1747-1793).

Paris, Palais Royal, and Raincy, collection of Louis Philippe Joseph d'Orléans (known as Louis Philippe II), duc d’Orléans. The painting was not mentioned in the 1757, 1765, and 1770 editions of d’Argenville’s Voyage pittoresque. According to Champier, this was because during this period it had been moved to Louis Philippe II’s château at Raincy. By the time of the 1778 edition of d’Argenville’s Voyage pittoresque, the painting was listed as in the Palais Royal, in the “Première pièce d’enfilade au Grand Salon” where it was described as “Le Bal, de Watteau.” In 1788, the painting was recorded in an inventory prepared in anticipation of the sale of the Orléans collection to Christie’s of London: Catalogue of the Orleans Collection of Pictures—État general des tableaux appartenans à S. A. Mgr. le duc d’Orléans dressé au mois de mars 1788. The picture is listed as “Watteau Un bal Champêtre.”

The painting was engraved later in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century by Jacques Couché for the publication Galerie du Palais Royal (1786-1808), 3: n.p.: “LE BAL CHAMPÊTRE. De la Galerie du Palais d’Orléans . . . TABLEAU D’ANTOINE WATTEAU. Peint sur toile , haut de 2 pieds, sur 2 pieds 11 pouces de large. Le lieu de la scène est un bocage. Deux personnes en costume de fantaisie, se livrent au plaisir de la danse, au milieu d’une société assez nombreuse, trois musiciens jouent des instrumens . . . .“

The subsequent changes in the provenance of Le Bal champêtre are tied to the precarious state of affairs surrounding the entire Orléans collection just before the Revolution; see Sutton, “The Orleans Collection” (1984). The collection was divided into two parts and sold in 1792. One major portion was purchased by a Brussels banker, Vicomte Edouard de Walkuers, who sold it to his cousin, comte Laborde de Mereville of Paris. He, in turn, sold it to a London “house of eminence,” actually to Michael Bryan (1757-1821; a London auctioneer).

London, Michael Bryan. His portion of the Orléans paintings was further divided into two parts and shown simultaneously at two London venues beginning on Dec. 26, 1798, one portion at Bryan’s own rooms in Pall-Mall and the other half at the Lyceum. The Bal champêtre appeared at the second venue: sale, Lyceum, A Catalogue of the Orleans’ Italian Pictures, December 26ff, 1798, lot 290: “Watteau - - - A Ball.” According to an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Watson Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the painting sold for £30. That note notwithstanding, it apparently was not sold, since it reappeared a year later among other unsold Orléans paintings that were put up at auction.

Sale, London, Bryan’s Gallery, Feb. 14, 1800, Orléans collection, lot 5: “Watteau . . . A Fête Champetre.” It sold for £11.11.0 according to an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie.

London, collection of Humphrey St John Mildmay (1794-1853). While in the Mildmay collection, the painting was listed by Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854-57), 4: 158: “ANTOINE WATTEAU.—In a free space, surrounded by wood, are a couple dancing a minuet. On the right three musicians, on the left a party of five ladies and four gentlemen looking on. Five of the party are recumbent. Very happily composed, of striking effect of light, and rendered throughout, including the trees, with as much spirit as care.” When Waagen saw the collection, in either 1854 or 1856, Humphrey St John Mildmay had already died and it now belonged to one of his sons, whom Waagen designated only as the “present youthful possessor.” There were actually two sons: Humphrey Francis Mildmay (1825-1866) and his younger brother, Henry Bingham Mildmay (1828–1905). The older brother died young, and thus the painting ended up with Henry Bingham Mildmay.

London, collection of Henry Bingham Mildmay. His sale, London, June 24, 1893, lot 84: “ANTOINE WATTEAU . . . LE BAL CHAMPETRE A cavalier in pale blue dress, with pink ribbons, holding castanets and dancing a minuet with a lady in crimson dress in the centre. Three ladies and two gentleman seated on the left, and four others standing behind them; a group of three musicians seated on a bank on the right / 36 ½ in. by 49 ½ in. / From the Orleans Gallery / Engraved by J. Couché / See Illustration.” The painting sold for £3517.10.0 to C. Wertheimer, according to annotated copies of the catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie and the Witt Library.

Paris, collection of Charles Sedelmeyer (1837-1925; Austrian-born art dealer established in Paris). The painting was published in Galerie Sedelmeyer, Illustrated Catalogue of the 1st Series of 100 Paintings by Old Masters, 1894, cat. 82: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) … Le Bal Champêtre / Three musicians are on the left: two seated on the ground, the third standing behind them, respectively playing on a violin, bag-pipe and clarinet. They are dressed in the peasant garb of the beginning of the 18th century. In the centre, on a sward, a gentleman and lady are dancing the menuet; the former, with castanets, dressed in light blue, with red bows and trimmings, is full of movement; the latter in dark red with a pink coif, with her hands on her skirt is more composed. The spectators are grouped on the right: five ladies and four gentlemen, those behind are standing, whilst those in the front, are seated; one gentleman is lying down. The light dress of the lady seated in the middle, contrasts with the darker shades of blue and red, in which the others are dressed. Both on the right and left, are magnificent clumps of trees with dense foliage, which here and there begins to assume the brownich [sic] tints of autumn. The beautiful sky is partly covered with light clouds. Canvas, 37 ¼ in. by 50 in. From the Orléans Gallery and Bingham Mildmay’s Collection. Engraved by J. Couché.”

Paris, collection of Ferdinand-Raphaël Bischoffsheim (1837–1909; banker and politician) and then his son Maurice (1875-1904). Stryienski, La Galerie du régent (1913), lists Le Bal champêtre in Bischoffsheim’s collection. It was ultimately inherited by Bischoffsheim’s granddaughter, Marie-Laure Henriette Anne Bischoffsheim (1902–1970), who in 1923 married Arthur Anne Marie Charles, vicomte de Noailles (1891–1981). In 1964 the painting was photographed in the Noailles’ Parisian residence in “Une des maisons-clés.” The picture passed to their daughter, Natalie Valentine Marie de Noailles (1927-2004), and still remains with the family.

EXHIBITIONS

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Het franse Landschap (1951), cat. 139 (as Watteau, Landelijke dans Le bal champêtre, without designation of lender).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P24 (as Watteau, The Country Ball [“Le bal champêtre”], lent by a private collector).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dezallier d’Argenville, Voyage Pittoresque (1749), 57; (1752) 66; (1778) 96.

Waagen, Kunstwerke und Künstler (1837), 1: 514.

Waagen, “Gemälde aus der Gallerie Orleans” (1837), 514.

Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854-57), 2: 499; 4: 158.

Waagen, “Notice sur des tableaux français” (1860), 267.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 112.

Champier, Le Palais-Royale (1900), 1: 390

Stryienski, Galerie du régent (1913), 102, cat. 371.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 293.

Dacier, “En étudiant l’œuvre gravé” (1923), 92-93.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 84.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 132.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 42, cat. 100.

Gauthier, Watteau (1959), pl. XVIII.

Jullian, “Maisons clés” (1964), 68-91.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 92.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 129.

Gétreau, "Watteau and Music" (1984), 532, 539, 544.

Gétreau, "Watteau et la musique" (1987), 243.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 100, 102, 137, 185, 195, 207, 321, 415, R37, R531.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 30.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), 164, 167-68.

Eidelberg, Rêveries italiennes (2015), 59.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Of the fourteen figures in Le Bal champêtre, only a handful can be traced to Watteau’s drawings, although many other studies have been associated with the painting.

Several drawings have been linked to the central woman dancing, but the most germane is a double study of a woman posed as if dancing, her skirt raised and held out to the side (Rosenberg and Prat 185). Grasselli proposed that the study at the left was used for Le Bal champêtre, but Rosenberg and Prat seem reluctant to accept the idea. Yet the correspondences are striking, not only in the general pose of the body and head, but also in smaller details such as the position of the fingers on her right hand. The general treatment of the skirt is similar, and both show a strengthening of the small folds just below the waist. The most notable difference between the drawing and the painting is the reversal of the figure, but Watteau could easily have relied on a chalk counterproof. He might have employed a separate, more detailed study of the woman’s facial features, but, on the other hand, he often freely improvised directly on the canvas.

Watteau borrowed two figures from an early sheet of studies now in Dijon (Rosenberg and Prat 137). The standing man second from the left in the top row, his hand resting on his hip, was used for one of the people in the group at the right. The seated woman on the bottom row of the Dijon sheet, at the far left, reappears in the right foreground of the painting. In the drawing she sits on a small stool, whereas in the picture she appears to be perched on an unseen hillock.

Several Watteau drawings have been cited in relation to the musicians at the left of the painting, but perhaps the most direct relationship is between the violinist and a study in a New York collection (Rosenberg and Prat 100).

Grasselli proposed that the bagpipe player was derived from a study in a private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 195), and although Rosenberg and Prat rejected that association, it seems worthy of consideration. The cast of the upright torso, the position of the legs, and the face seen in profile correspond closely. Yet, in the painting, the bagpipe player’s left elbow is extended out farther, his body is less upright, and his head is turned at a slightly different angle. Perhaps Watteau used another, more closely related study.

Of several studies of a man playing a hautbois or oboe, the one most convincingly close to the musician in Le Bal champêtre is a partial study of the musician’s arms and hands in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 321). The positioning of the fingers corresponds to that in the painting, but this may be only a function of the instrument.

REMARKS

Le Bal champêtre is related compositionally to two other fêtes galantes by Watteau: La Musette and a work, not extant, that was engraved under the same title of Le Bal champestre. Like our picture, both these compostions feature a man and woman dancing in the countryside, with many onlookers. La Musette preserves all of the figures found at the right except for the rightmost pair. Also, it lacks the musicians at the left, and the pose of the male dancer is different. In Ravenet’s engrving of Le Bal champestre, the central dancers are essentially unchanged, but almost all of the other figures differ; even though there are musicians at one side, they are not the same. Of the three works, the Orléans version is by far the largest, the version engraved by Ravenet was middle-sized, and La Musette is the smallest, approximately one-third the size of the Orléans painting.

Scholars have not sufficiently considered the order in which the three variants were painted. Generally, the Orléans version has been placed in Watteau's middle career. Mathey proposed 1712, which is undoubtedly too early. Roland Michel proposed c. 1713-14 and Adhémar suggested a year as late as 1716, which, given the stiffness of some of the figures at the right, seems too late. Rosenberg and Prat assigned the last of the related drawings to c. 1714. The painting engraved by Ravenet was dated 1715 by Adhémar, and the most mature drawings associated with the painting (Rosenberg and Prat 275 and 502) have been dated by these scholars to c. 1715 and 1716-17 respectively. The greater grace and fluidity of the painting allows this as a possible date. While La Musette is more directly related to the Orléans painting, the differences are telling and suggest too that this version was a later repetition of the Orléans painting. Whereas the first two are crowded scenes with far too many people, in the Flemish mode of Watteau’s early fêtes galantes (such as L’Accordée de village and Les Comédiens sur la champ de foire), La Musette, though retaining many of the figures from the Orléans painting, has a smaller number and an open, asymmetrical structure that looks forward to Watteau’s later works. Too often scholars attempt to date his paintings in a precise, sequential order, with the second version painted after the first was finished. But this may not have been the case with Watteau. He may have worked on them simultaneously and, complicating matters further, he seems to have worked on his pictures sporadically, stopping and then starting again after a considerable lapse of time.

When Adhémar wrote that there were “nombreux tableaux de ce genre par Lancret,” she probably was referring only to the idea of pastoral compositions centering on a female dancer with outspread skirt and a male dancer striking graceful attitudes. There are no specific relationships between these Lancret paintings and Le Bal champêtre, but the general correspondence reminds us once again how Watteau’s paintings established basic formulas that his followers repeated for decades to come.

A significant quandary is raised by the remarkably large size of the painting in Fontainebleau. According to the caption on the Couché engraving, Watteau’s fête measured 2 pieds by 2 pieds, 11 pouces, that is, 61 by 88.9 cm. Yet the painting in Fontainebleau is much larger, essentially a third larger at 96 by 128 cm. This discrepancy is not explained away easily, yet the quality of the painting is high and its provenance is relatively unbroken. Even more curious, the version in Bucharest (copy 1), at 69.2 by 95 cm, more closely coincides with the dimensions cited on the Couché engraving.

The way that the right side of the Fontainbleau painting is terminated raises a question as to whether it may have been cut at the right, and cut before the Couché engraving was executed. In the actual painting and in the Couché engraving the rightmost pair of strollers look back and down as though they were moving forward but still speaking to unseen characters farther to the right. This type of grouping, with standing and seated figures responding to one another, can be found in various Watteau compositions such as L’Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune and L’Amour paisible. In a Philippe Mercier drawing that depends heavily on Watteau's inventions, the strolling couple at the right side similarly looks back and down to a couple. It is a logical extension of an implied narrative. Moreover, it is an otherwise inviolable rule that Watteau arranged the outermost figures to turn back to the center of the composition. From this, might one not wonder whether Le Bal champêtre was cut at some point in the eighteenth century, resulting in the present atypical configuration?

For copies of Le Bal champêtre, CLICK HERE