- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Bal champestre

Entered March 2016; revised September 2016

Presumed lost

Oil on canvas

54.5 x 54.5 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Récréation champêtre

RELATED PRINTS

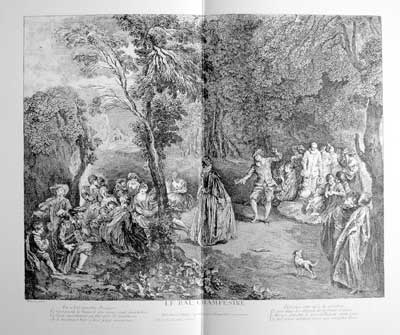

Simon François Ravenet after Watteau, Le Bal champestre, engraving, c. 1735-40.

Watteau’s Le Bal champestre was engraved in reverse by Simon François Ravenet. The print was not commissioned for Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé, but was executed independently, around 1735-40. Ravenet executed an engraving after Watteau’s Départ de garnison about 1737, and he probably executed this one at the same time. By 1745, Ravenet had left for London and was working with William Hogarth on the Marriage à la Mode series.

PROVENANCE

There is no record of who owned the painting in the eighteenth century nor can it be traced subsequently.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 111.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), no. 16.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Julienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 129; 3: cat. 311.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 85.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 131.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 112.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 102, 185, 208, 275, 390, 481, 502, 535, 538.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Of the more than twenty-five figures in Le Bal champestre, only a quarter of them can be traced to Watteau’s studies from the model.

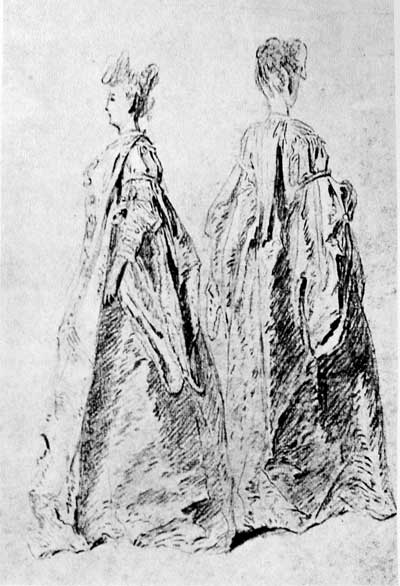

The female dancer, seen from behind, with a cape over her shoulder and a small bonnet perched on her head, derives from a study in the Teylers Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 394). Watteau used this same dancing woman for Les Plaisirs du bal, but there she is paired with a differently posed male dancer playing castanets.

The enigmatic Pierrot, standing out among the many onlookers at the right side of the engraving, one hand in his pocket, the other holding his hat, stems from another drawing in the Teylers Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 535). This same figure was used again for the painting Pierrot, Mezzetin, Scaramouche, Scapin & Arlequin, now in the Getty Museum.

It has been proposed that the woman in the foreground, draped in the ample folds of her gown, was based upon a drawing whose present whereabouts are unknown (Rosenberg and Prat 208). The distinctive diagonal fold descending through her skirt is present in the drawing and in the painting, but there are few other similarities. The other major folds of her costume, the turn of her head, the position of her hand—all these features are different. This brings into question whether Watteau used this drawing or perhaps some other study was used for his painting.

The character of Harlequin, standing behind Pierrot in his standardized pose of comic mockery, was studied by Watteau on a sheet of miscellaneous figures in École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts (Rosenberg and Prat 481). While there is no reason to deny this association, it should be pointed out that this drawing is often related to Watteau’s oeuvre because Harlequin appears in so many of the artist’s pictures and always in the same pose (Le Rêve de l’artiste, Les Entretiens badins, Les Comédiens italiens, and Les Plaisirs du bal).

The woman seated on the ground just in front of Harlequin, seeming to turn away from her companion’s entreaties, was based on a beautiful sheet in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 502). Her costume, the turn of her head, and the gesture of her upraised hand correspond exactly.

The woman seated on the ground, seen from behind, intently regarding her amorous companion, was taken from a drawing now in the National Gallery of Ireland (Rosenberg and Prat 390). The woman just beyond her, leaning backward, derived from a study in which she is posed in a chair, leaning forward at the very same angle as in the painting (Rosenberg and Prat 275).

It has been proposed that a tiny study of hands in a third drawing in the Teylers Museum, a sheet with six studies of actors (Rosenberg and Prat 102), was used for the hands of the principal male dancer in Le Bal champestre. Perhaps this is so, but a full study of the dancing man must also have guided Watteau.

REMARKS

Despite the similarity in name between this composition and Le Bal champêtre, a painting that was once owned by the duc d’Orléans and is now in a Fontainebleau collection, they have little in common. Certainly, they share the common theme of a large assembly of ladies and gentlemen in a forest clearing watching a man and woman dancing, but except for the male dancer, they do not have any other characters in common. For example, the female dancer is a different model, and although both works depict a trio of musicians at one side, the musicians and their instruments are not the same. So too, the courting couples are all different.

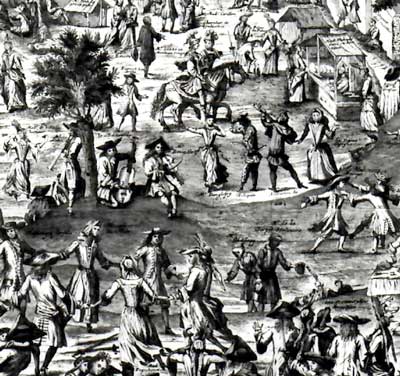

A significant aspect of Le Bal champestre is its inclusion of fashionably dressed members of Parisian society as well as Pierrot, Harlequin, and other characters from the commedia dell’arte. If Watteau’s fêtes galantes often evoke a theatrical atmosphere, here the fête is presented quite specifically yet still equivocally. Is this theater or is this real life? As can be seen in a French print of the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century showing the fair at Bezons, a small theatrical group acts and dances to musical accompaniment, while ladies and gentlemen dance in a circle in the adjacent space. The cartouche at the top of this panoramic scene alerts us that “l’on voit une affluence prodigeuse de personnes de toute Condition la plupart déguisées.” A similar mélange appears in an exceptional painting by Joseph Parrocel (1646-1704), also dating to the very end of the seventeenth century or the very first years of the eighteenth.

Watteau, Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, 64.7 x 91.3 cm. Potsdam, Schloss Sans Souci.

In a painting in Potsdam, Watteau shows a fair like that in the engraving, with eating and dancing everywhere, people in costume, and a troupe of comedians mingling with the public. The Pierrot near the center, dressed in white, bows and holds his hat down in front of himself much as in Le Bal champestre. The Potsdam painting still adheres to the Flemish tradition of multi-figured fairs and kermesses of the seventeenth century, but Le Bal champestre, reduces the number of characters and invests them with a greater sense of narrative and emotion, as Watteau anticipating the more mature and poetic aspects of the fête galante.

The dating of Le Bal champestre has not been a subject of much discussion. Of those who have voiced an opinion, most favor the mid-point of Watteau’s career, c. 1715-16. Adhémar, for example, places the painting c. 1715, and Montagni and Macchia parrot this opinion. Rosenberg and Prat have dated most of the drawings used for the painting as c. 1715-16, but assigned a date c. 1717 to the most advanced, such as those of the seated woman (Rosenberg and Prat 502) and the standing Pierrot (Rosenberg and Prat 535). Indeed, while the overall scheme of this multi-figured composition might suggest an earlier date, the sophistication of some of the individual figures suggests the artist’s growing maturity. All this might be more evident if only we had the actual painting to consider.

Apart from Ravenet’s engraving, we know almost nothing about Watteau’s original painting. Most modern critics have identified the picture with one sold from the collection of the duc de Chabot, supposedly in 1769—a tradition that goes back at least as far as the Sedelmeyer Gallery’s 1905 publication, cat. 74 (see copy 1). Among the scholars who have cited Chabot as the original owner are Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Réau, Adhémar, and Macchia and Montagni. Yet there is no documentary proof of this ownership with the duc de Chabot. None of the scholars who have accepted this provenance have specified the exact date of the Chabot sale or the lot number, nor have they quoted the text of the supposed 1769 catalogue. Indeed, although there were several sales in the eighteenth century with works from the duc de Chabot’s collection, as far as can be determined, there was no sale in 1769 and his other sales did not contain Le Bal champestre. In short, there is no indication that he owned the painting.

For copies of Le Bal champestre, CLICK HERE