- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Les Bergers

Entered July 2016; revised November 2024

Berlin, Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Schloss Charlottenburg, inv. GK 15303

Oil on canvas

56 × 81 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Die Hirten

The Shepherds

RELATED PRINTS

This painting was not included in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé, which explains why it was largely unknown until the late nineteenth century. It was ultimately engraved by the Berlin-based Gustav Eilers (1834-1911).

PROVENANCE

Rheinsberg, collection of Frederick II [Frederick the Great] (1712-1786; king of Prussia), 1742–1745; Potsdam, Stadt Schloss, 1745-1786.

German Royal Collection, Berlin, Schloss Sansouci, before 1825-1829/30; Berlin, Stadt Schloss; Potsdam, Neues Palais, 1882-1931; Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, 1931-41; Konigsberg, 1941; Wildpark; Berlin, Kurfürst Bunker, 1945; 1947-53 Wiesbaden, Central Collecting Point, 1947-1953, Dahlem, Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, 1953-61; Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, from 1961 to present. Data concerning the painting’s whereabouts within the royal collection are taken from Vogtherr’s 2011 publication.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Exposition universelle, Frédéric le Grand (1900), cat. 28 (by Watteau, Les Bergers, lent by the Emperor of Germany).

Paris, Palais national, Chefs-d’oeuvre (1937), cat. 234 (by Watteau, Les Bergers, lent by the Palais Neuf, Potsdam).

Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, Malerei des 18. Jahrhunderts (1947), cat. 115 (by Watteau, Die Hirten, lent by Verwaltung Schlössern und Gärten).

Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, Französische Kunst (1951), cat. 58 (by Watteau, Die Hirten, lent by Verwaltung Schlössern und Gärten).

Potsdam, Charlottenburg, Meisterwerke (1962), cat. 91 (by Watteau, Die Hirten, lent by Staattliche Schlosser und Gärten).

Paris, Louvre, Peinture française (1963), cat. 34 (by Watteau, Les Bergers, lent by Staattliche Schlösser und Gärten).

Washington, Paris, and Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P53 (by Watteau, The Shepherds [Les Bergers], lent by Schloss Charlottenburg, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, Berlin).

Ottawa, National Gallery, Age of Watteau (2003), cat. 7 (by Watteau, The Shepherds, lent by the Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin).

Paris, Grand Palais, Poussin, Watteau, Chardin, David (2005), cat. 182 (by Watteau, Les Bergers, lent by the Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten, Schloss Charlottenburg).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Osterreich, Description (1773), possibly cat. 266, 276, 286, 292, or 299.

Osterreich, Beschreibung (1773), possibly cat. 266, 276, 286, 292, or 299.

Dohme, “Die Französische Schule des XVIII. Jahrhunderts” (1883), 97.

Fourcaud, “Potsdam à Paris” (1900), 272.

Lafenestre, “La Peinture ancienne” (1900), 554-55.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), no. 85.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 77.

Brinckmann, Watteau (1943), 28 no. 56.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 143.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Schefer, “Visible et thématique” (1962), 50.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 176.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B37.

Cailleux, “Un Étrange monument” (1975), 85-87.

Cailleux, “A Strange Monument” (1975), 246-47.

Saint-Paulien, “Les Beaux-Arts et la tradition du faux” (1976), 54.

Mirimonde, L'Iconographie musicale sous les rois Bourbons (1977), 2: 60, 118.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 215.

Posner, “Swinging Women” (1982), 77.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 187, 210, 229, 269-70, 301.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 25-26, 166-69.

Baticle, “Le Chanoine Haranger” (1985), passim.

Rosenberg, “Répétitions et répliques” (1987), 105-06.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Paysages, paysans (1994), 160-61.

Jollet, Watteau (1994), pl. 34.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 120, 310, 445, 454, 460, 489, 491, 557, 611, R419.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 98, cat. 88.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 134.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. 4.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Les Bergers is a later variant of Watteau’s Le Plaisir pastoral in Chantilly, although only three couples from the Chantilly painting are repeated in the Berlin version: the principal dancers, the amorous couple at the left, and the man pushing the woman on the swing in the background. Also, the dog licking itself in the foreground remains the same. It is evident that Watteau had an image to guide him in making the second version, yet the question arises as to whether he created the Berlin version directly from the painting in Chantilly or from his original studies from the model. As will be seen, it seems he largely depended on the Chantilly picture.

If we compare Watteau’s original study for the woman on the swing (Rosenberg and Prat 310) with the depictions of her in the Chantilly and Berlin pictures, it is evident that Watteau remained faithful to his invention in both instances. One interesting exception is that while the woman in the drawing is shown with a small cap, her counterparts in the paintings do not wear this head covering, suggesting that the change was instituted in the first picture, Le Plaisir pastoral, and carried over to the second, Les Bergers.

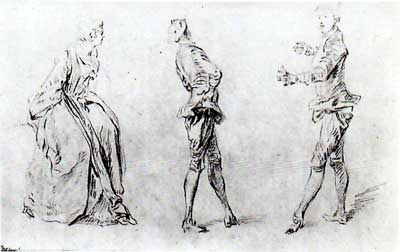

The Watteau drawing for the man pushing the swing has not survived. However, it has not been noticed until now that an echo of the drawing appears on a sheet of three copies after the master (Rosenberg and Prat R419). The two studies of men on that sheet, at center and right, are copies after the same model, in the same costume, striking similarly exaggerated poses that are of the same moment. It is likely that originally Watteau drew them together on one sheet. Whether the original study of the woman was on that or another sheet is moot.

Rosenberg and Prat claimed that the left and central figures were copied not from Watteau’s original drawings but from plates 279 and 160, respectively, of the Figures de différents caractères. Yet their argument does not hold because these two figures appear in the opposite direction of the engravings. Indeed, all three figures accord with the direction of Watteau’s original studies. Moreover, and most important, the scholars' explanation does not define the source for the man pushing the swing, a figure not recorded in the Figures de différents caractères.

Watteau evidently referred to his original drawing for the man pushing the swing in Les Bergers. Curiously, the comparable figure in Le Plaisir pastoral is not fully delineated: his left arm is higher and the hand is not shown, and nothing of the right arm or hand is visible. The Chantilly figure could not have been the source for his counterpart in Berlin. Watteau must have used his original study from the model. This is a unique situation because in most other instances Watteau turned to the Chantilly painting rather than his original studies from the model.

The woman pulling away from her aggressive suitor is based on a full study of the figure (Rosenberg and Prat 489). She appears in both the Chantilly and Berlin pictures with no apparent change, save that in both paintings a swath of cloth covers her lap—an element of costume not present in the drawing. As with most such changes, the variation was introduced first in the Chantilly picture and then carried over to the Berlin painting.

Another confirmation of Watteau’s working method can be seen in the evolution of the dancing woman. She can be traced back to a slight Watteau sketch (Rosenberg and Prat 120). Although this drawing is somewhat removed from the Chantilly and Berlin paintings, it unquestionably served for the woman dancing at the center of Watteau’s L’Accordée de village in the Sir John Soane’s Museum, and in Le Contrat de mariage in the Prado. In both instances, she is coupled with a male partner who strikes a distinctive pose, with his head cocked and his left hand held aloft. This same couple then reappears in Le Plaisir pastoral in Chantilly. Here the woman’s appearance has been significantly altered: a prominent, rose-filled sash is draped across her back. This change was then repeated in the Berlin painting. This element of her costume is a clear indication that the artist again relied on the Chantilly painting when executing the Berlin canvas. To a degree, the colors of the two dancers’ costumes help affirm that the Chantilly painting was the model of the Berlin version. In both, the woman’s skirt is yellow and the sash blue.

A similar progression can be seen in the evolution of the male dancer. Although the original study from the model is not extant, its appearance can be approximated from Watteau’s early paintings, L’Accordée de village and Le Contrat de mariage. It was then taken over, essentially without change, for Le Plaisir pastoral in Chantilly. There are some changes in the costume: a beret replaces the hat, and bows appear over the right shoulder. Presumably these features were not present in the original drawing but were added during the execution of the Chantilly painting. Finally, in the Berlin painting, Watteau not only changed the tilt of the man’s head and beret, and eliminated the white linen peeking out under the jacket, but he also made the costume more elaborate, adding a plume to the beret, a large bow to the shoulder, and rosettes to the knees. That he referred to the Chantilly painting is also evident in his maintaining the pas de deux of the two dancers.

Another key for our understanding Les Bergers is the figure of the shepherd plying his suit with the reluctant object of his affection. The source for this man would seem to be a beautiful drawing in the Musée Cognac-Jay (Rosenberg and Prat 445). The drawing shows an elegantly dressed member of society with a calm expression calm, quite unlike that of the shepherd in the two paintings in Chantilly and Berlin. As painted, he lunges forward violently, and his expression is much more intent. Parker and Mathey, as well as Rosenberg and Prat, favor the idea that this was the drawing used for the paintings, whereas Grasselli demurred and, given the extreme differences between the drawing and the paintings, one can well appreciate why she did so. If the Cognac-Jay study was indeed the one that Watteau employed, however, as in the case of the other figures discussed above, he transformed it in the Chantilly painting and retained that transformation in the Berlin painting. He did not revert to his drawing for the second painting.

Watteau, Two Studies of a Musette Player, red, black, and white chalk, 26.7 x 22.1 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

Watteau, Les Bergers (detail).

A double study of an actor playing a musette, a courtly version of a bagpipe, was used for Les Bergers (Rosenberg and Prat 460). The study of him at the left side of the page was employed for the musician in the Berlin painting with almost no significant change except for the slight tilt of his head enabling him to watch the dancers. Interestingly the other study on this page, showing a side view of the musette player, was employed by Watteau for L’Accordée de village—the same painting where the dancing couple first appeared.

Watteau, Study of a Seated Woman, graphite, red chalk, gouache, 20.4 x 13.7 cm. France, private collection.

Watteau, Les Bergers (detail).

The woman next to the musette player was taken from a Watteau study last known in a French private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 491). In both the drawing and the painting she wears a pearl necklace, jewelry that sets her apart from the peasants.

Watteau, Study of a Man with a Pointed Hat, red and black chalk, graphite, 19 x 15.5 cm. United States, private collection.

Watteau, Les Bergers (detail).

In the Berlin painting, a young man in a tall pointed hat peers over the musette player’s shoulder. This bust-length character was based on a study now in an American private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 611).

REMARKS

An interesting hypothesis was put forward by Christoph Vogtherr in 2003, at the time of the exhibition in Ottawa. He proposed that since the musette player is sometimes identified as Watteau’s friend, the abbé Haranger, he was the original owner of the picture. As corroboration, Vogtherr points out that in the May 17, 1735, post-mortem inventory of the abbé’s collection, under no. 28, was a painting: “Un tableau peint sur toile représentant une bergerie.” However clever the theory, the identity of the long-haired man as Haranger is not definitive, especially since in the past he was identified as the actor La Thorillière. Moreover, as this character appears in several of Watteau’s paintings, it seems unlikely that the association with Haranger, per se, is sufficient evidence that he owned any of them. Finally, the generic “bergerie” is only a vague indication of subject and, not least, there is no specific link to Watteau. The Haranger inventory does not list the names of artists. Thus Haranger’s bergerie might have been by another French artist or even a Dutch or Flemish one, and it should not be linked with Watteau on such slender evidence.

Les Bergers has generally been identified with cat. 543 of Osterreich’s 1773 catalogue of Frederick the Great’s art collection (see, for example, Rosenberg in 1984 and Vogtherr in 2011). The listing there reads “Watteau. . . L’agrément du Bal. C’est le titre sur lequel on a gravé ce tableau à Paris, comme aussi les deux qui suivent.” However, Les Bergers was not engraved in France. There are many other Watteau paintings in the catalogue whose descriptions could fit Les Bergers and that were not claimed to be engraved:

266. Une Conversation dans une contré champêtre

276. Une Conversation dans un Bis; grand tableau . . . Il y a beaucoup de grace dans ce tableau

286. La Danse; beau tableau

292. L’amusement du Bal

299. La Danse. Il y a un bel effet dans ce tableau

Rosenberg has proposed identifying Les Bergers with a Watteau painting mentioned by Voltaire in a letter of January 1741 to Bonaventure Moussinot. In the letter, Voltaire described paintings in the collection of Frederick the Great: “une espèce de noce de village, ou il y a un viellard en cheveux blanc très remarquable.” This reference has normally been linked with Watteau’s La Mariée de village, but as Rosenberg argued, there the old actor with the white hair is a minor player whereas in Les Bergers he is a more central, memorable figure. Unfortunately for Rosenberg’s thesis, Les Bergers cannot easily be considered a village wedding. It should be remembered that Voltaire was writing from Brussels and may have confused things slightly. Perhaps he was remembering the striking white-haired actor in Les Bergers but conflated it with La Mariée de village. Even if there was confusion, Voltaire’s remark could establish that Les Bergers had arrived in Berlin by late 1740.

Like other Watteau paintings hidden from view in the German royal collection, this picture remained essentially unknown outside that country until the late nineteenth century. Moreover, since it was not engraved in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé, the composition was not listed by early Watteau scholars such as Hédouin and Goncourt. The situation changed dramatically after the painting was exhibited publicly at the Paris World’s Fair of 1900.

Ever since the painting became known to scholars, it has always received the highest praise. It is well preserved, its colors are glowing, and its graceful characters are monumental. When shown in Paris in 1900, Fourcaud and Lafenestre were rightly amazed by the picture’s freshness and wonderful state of preservation. The only dissenting voice in modern times came from Ferré’s 1972 publication, where Saint-Paulien is quoted as describing the painting as a “Tardif pot-pourri wattesque. Ni l’organisation de l’espace, ni la touche, ni le coloris ne sont de J.-A. Watteau.” Ferré cast the painting into his “B” category (“peintures attribués à Watteau”). As Cailleux noted in his justly scathing critiques of Ferré’s publication, if he believed it was a late pastiche, why did Ferré not classify it under “C” (pastiche de Watteau)? Cailleux theorized that Saint-Paulien, a noted Nazi sympathizer, was offended by the supposedly sexual activity of the dog. But it may well be that Ferré and Saint-Paulien were also perniciously trying to discredit the Berlin painting to make room for a painting known as Divertissement champêtre, a pastiche of Watteau’s Le Plaisir pastoral that they claimed was an autograph Watteau.

It is instructive to compare Les Bergers with Watteau’s earlier version of essentially the same composition, Le Plaisir pastoral at Chantilly. Les Bergers is almost twice as large (Watteau tended to work on a larger scale later in his career), and the lighting is brighter. By contrast, the foreground of Le Plaisir pastoral is dark and the forms less clear. Whereas Watteau repeated many of the figures from the first composition, there are telling modifications. The male dancer, for example, moves with greater fluency as can be seen in his upraised arm and bent leg. The shepherdess rejecting her suitor’s forceful advances is richer and more fully rounded in the Berlin version. Similarly, whereas the recumbent shepherd in the first version is awkwardly positioned with his arm behind his back (a pose Watteau used in a number of early compositions), in Les Bergers a very different youth assumes a sophisticated, more three-dimensional pose that is more successful. Not least, this character is placed farther to the left, closer to the foreground, more in alignment with the diagonal thrust of the now pronouncedly asymmetrical composition. Indeed, the composition of Le Plaisir pastoral is planar and somewhat stiff, but the diagonal arrangement of Les Bergers has a more organic unity. In its brilliance of color and special refinement, Les Bergers is like the celebrated Plaisirs d’amour in Dresden. Both mark the triumph of Watteau’s mature skills.

There is general consensus that Les Bergers is a late work, painted after the Chantilly Le Plaisir pastoral, a picture generally thought to have been executed around 1715-16. Adhémar dated Les Bergers to 1716, between the spring and fall of that year; however, she foolishly tried to squeeze seventy-five pictures into that narrow span of time, thus bringing her chronology into question. Mathey also chose 1716 for Les Bergers. Montagni and Macchia dated the painting to 1717. Huyghe, Nemilova, and Roland Michel dated it still later. Likewise, in 1984, although Rosenberg did not assign a specific date to the painting, he thought there was an interval of more than two years between Le Plasir pastoral (dated no earlier than 1716, he claimed) and Les Bergers, which would imply a date no earlier than 1718 for Les Bergers. Temperini and Glorieux placed Les Bergers at 1717-18. Rosenberg and Prat dated the drawing of the youth with the pointed hat to 1718, thus providing a terminus post quem for the painting. In short, there has been a tendency in recent years to date the painting increasingly later in the artist’s career.

There has also been an increasing tendency to read the painting in emblematic and sexual terms. Schefer in 1962 saw the curled up dog licking its genitals as signifying “abandon,” with the implication that this reflected the human characters’ emotions as well. Roland Michel has read the painting as expressing lustful desire. She claimed that the male dancer gazes at his partner avidly, and the woman next to the musette player is seemingly unaware that her male companion (the man with the pointed hat?) is unlacing her corset to release her already exposed breasts. Likewise, Roland-Michel saw a contrast between the lust of the man at the left whose face expresses forceful desire as he grasps the woman’s breast and, on the other hand, the gentleness of woman's rebuff of his advance.

Posner claimed that Le Plaisir pastoral and Les Bergers possess symbolic structures revolving around the theme of love and desire. The narrative supposedly begins at the back left with the woman on a swing symbolizing inconstancy and fickleness, leaving her male companion uncertain whether to push her or step away. Together, they launch the game of arousal and love. Both women at the left foreground have exposed breasts, and the leftmost has indeed incited her companions to physical attack. According to Posner, the dog licking his genitals is a vulgar symbol of sexual longing felt by the young man seated in the foreground. Finally, the musette player, whose inflatable instrument is read as a phallic symbol, plays the tune to which all participants respond according to their class and personality. Posner’s elaborate and explicit reading should be understood in relation to his overriding imposition of sexuality on Watteau’s art. Rosenberg followed Posner’s interpretation quite closely.

While one might not agree with specific details of these interpretations of Watteau’s Les Bergers, the picture is unusually physical and explicit.

Click here for copies of Les Bergers