- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Bosquet de Bacchus

Entered July 2016; revised December 2024

Presumed lost

Materials unknown

51.3 x 62.3 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

The Grove of Bacchus

Riunione presso una fontana

RELATED PRINTS

-sampled.jpg)

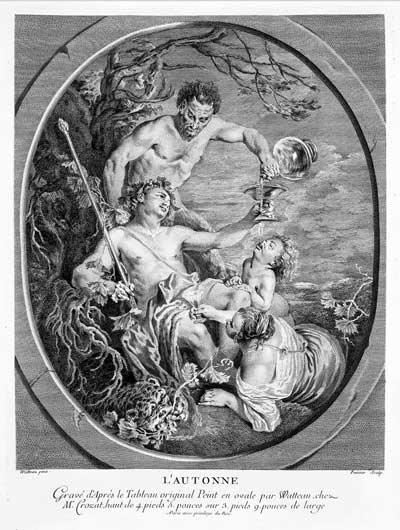

This Watteau painting was engraved in reverse by Charles Nicolas Cochin. The print was announced for sale in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure de France (page 2676).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory); this is cited in the caption underneath the 1727 engraving: “du Cabinet de Mr de Jullienne.” It was no longer with Jullienne by 1756, when the catalogue of his collection was prepared—now in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 118.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 120.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 113.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), n. 113.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), no. 132.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Julienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 265; 3, cat. 265.

Dacier, La gravure de genre (1925), 60.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 120.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 141.

Macchia and Montagni, Tutti l’opera di Watteau (1968), cat. 141.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 218.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 204, 266, 299, 302.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 221, 398, 402, 409, 553, 505, G13.

RELATED DRAWINGS

There are slightly over twenty figures in this composition but only seven of them, those in the foreground, can be considered principal characters. Two of the principal characters, the couple standing in front of the statue of Bacchus, can be traced to Watteau drawings: the woman was taken from the rightmost figure on a sheet of studies now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat 398), while her male partner, strikingly posed, was taken from a trimmed sheet in the Petit palais, Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 505). In both instances the actual drawings face in the opposite direction to their counterparts in Cochin’s engraving. This helps establish that Cochin engraved Watteau’s painting in reverse.

The guitarist on the right side of the engraving is taken from an interesting sheet in a private Vaduz collection (Rosenberg and Prat 402). On this sheet the artist studied his model twice, and added a separate study of the face in the upper corner. For the painting, Watteau selected the rightmost study and joined to it the separate study of the head.

The charming, shy girl seated slightly behind the guitarist is taken from a drawing in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 409).

-sampled.jpg)

Cochin after Watteau, Le Bosquet de Bacchus (detail).

The figures in the middle ground are closely related to those in the middle ground of L’Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune but, due to the scarcity of evidence, it is difficult to establish the sequential relationship between the two paintings and Watteau’s original studies from the model. Two of the characters in Le Bosquet de Bacchus can be related to his drawings. The first is of the woman seated on the ground, with her back to us. She can be traced to a lost drawing, the counterproof of which was one of the sheets that Watteau sold to Count Tessin in 1715 and which now is in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat 121). Likewise Watteau’s study of a standing woman, holding the excess of the skirt’s material off the ground, was taken from a drawing in the Fogg Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 221).

REMARKS

Despite the fact that this is one of the most copied of Watteau’s compositions, it has received little critical attention. Had the actual painting survived, one imagines it would be much more in the forefront of Watteau studies.

One of the most striking elements in Le Bosquet de Bacchus is the dramatic Baroque fountain with its statue of the Roman god of wine. It is closely related to the fountain designs by Gilles Marie Oppenord that Watteau knew and had in his possession by 1715. Here a sybaritic Bacchus leans back and lifts aloft a goblet that spurts a jet of water into the air; a youth grasps a dolphin from whose mouth water gushes forward; and a seemingly dormant, perhaps inebriated leopard has water running from his mouth. By contrast, the sculptural group at Versailles of Bacchus and infant satyrs in a fountain dedicated to the four seasons is far more restrained, Bacchus has little sensuality, and his pose is more reminiscent of Annibale Carracci’s academic ignudi in the ceiling of the Palazzo Farnese.

If the sculptural richness of Watteau’s ensemble mimics Oppenord’s inventive fountain designs, it—especially the figure of Bacchus and the inebriated leopard— also recalls Watteau’s Automne from the Saisons Crozat. The two seem related not only in mood but also in time.

-sampled.jpg)

Charles Nicolas Cochin after Watteau, Le Bosquet de Bacchus (detail, reversed to the original direction of the painting), engraving.

Watteau and Quillard, L’Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune (detail). Madrid, Museo de Prado.

The complex of figures in the middle ground of Le Bosquet de Bacchus is closely related to the similar group disposed across the middle ground of L’Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune. This is especially true of the man standing under the statue, seen from behind and with a cape over his shoulders; the two women seated on the ground, facing each other; the strolling couple; the recumbent man on the ground, seen from behind and his hand in the air; and the woman opposite him, looking upward. These two fêtes galantes are also linked by the prominence of Opennordesque fountains in the gardens. These concordances suggest that the two paintings were painted around the same time, but in which order is a moot issue.

As with almost all of Watteau’s fête galantes, a great variety of dates has been assigned to Le Bosquet de Bacchus. Adhémar placed it between the spring and autumn of 1716, and slightly after L’Assemblée près d’une fontaine de Neptune. However, she placed some fifty paintings in this short period of nine months, an impossibly short period for so many paintings. Macchia and Montagni, always parroting Adhémar, dated the painting to 1716. Rosenberg and Prat have assigned dates between 1715 and 1716 for the drawings associated with the painting. Roland Michel posited c. 1717-18 as the date of the painting.

Click here for copies of Le Bosquet de Bacchus