- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

La Boudeuse

Entered August 2016; revised May 2022

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, inv. 4120

Oil on canvas

42 x 34 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

A Capricious Woman

La Capriceuse

A Conversation

La Conversation

A Man and Woman Seated in a Garden

A Man and Woman Sitting

The Sulking Woman

RELATED PRINTS

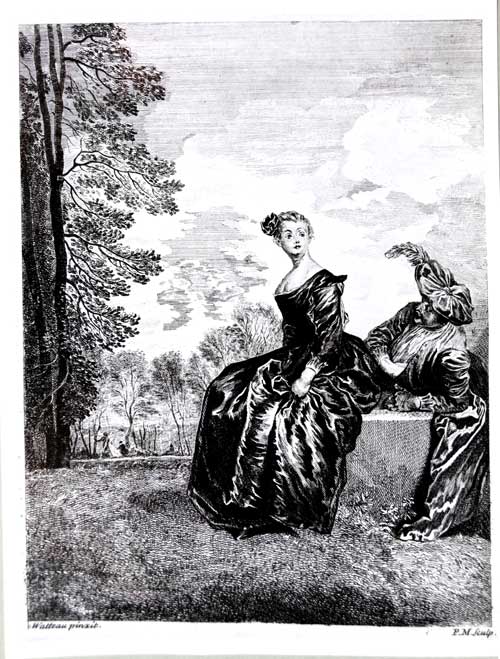

La Boudeuse was etched by Philippe Mercier c. 1725. It was noted by Pierre Jean Mariette in his "Notes manuscrites," vol. 9, fol. 192: “Une femme assise dans un jardin ayant derrière elle, un homme qui lui parle, gravé par Pierre [sic] de Mercier."

PROVENANCE

London, collection of Salomon Gautier (?-1725; art dealer). His sale, London, January 18-February 1, 1726, lot 34: “a Man and Woman sitting, Watteau.”

London, collection of Sir Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (1676-1745; Prime Minister of Great Britain). His sale, London, 1748, day 2, lot 52: “A small Conversation . . . Watteau.” Bought by his son Horace Walpole for £3.3, as recorded in Houlditch, Sales Catalogues (1760), 1:39.

Twickenham, Strawberry Hill, collection of Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (1717-1797; man of letters). His sale, Strawberry Hill, April 25ff, 1842, day 13, lot 36: “A Man and Woman seated in a Garden, a charming specimen, replete with interest, by WATTEAU / From Sir Robert Walpole’s collection.” Bought by Emery of Bury Street, for £40.19.

Paris, collection of Charles Auguste Louis Joseph, duc de Morny (1811-1865). His sale, Paris, May 24, 1852, lot 31: “[WATTEAU (Antoine)]. La Conversation. Composition de deux figures, dans la manière vénitienne du peintre. Toile.” Bought by Henri Didiér for 1,700 francs.

Paris, de Ferrol collection. His sale, January 22, 1856, lot 28: “WATTEAU (Antoine). La Conversation. (Collection de Sir Robert Walpole. Id. De M. le comte de Morny.)” Sold for 1,700 francs.

St. Petersburg, collection of Count Paul S. Stroganoff (1823-1911); transferred to the Stroganoff Gallery; seized in 1922 for the State Hermitage Museum.

EXHIBITIONS

Petrograd, Hermitage, Peinture française des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (1922).

Moscow, Pushkin Museum, An Exhibition of French Art of the 15th-20th Centuries (1955), 25.

Martin-Méry, La femme et l’artiste (1964), cat. 98 (as Watteau, La Capricieuse or La Boudeuse, lent by the Hermitage).

Budapest, French Art from the Hermitage (1969), cat. 25.

Leningrad, Hermitage, Watteau and his Time (1972), cat. 8.

Dresden, Meisterwerke aus der Ermitage Leningrad und aus dem Puschkin-Museum, Moskau (1972), cat. 48.

Melbourne, Old Master Paintings from the USSR (1979), cat. 39.

Washington, National Gallery, Watteau, 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 46 (as by Watteau, The Sulking Woman [La Boudeuse], lent by the Hermitage).

London, National Gallery, French Paintings from the USSR (1988), cat. 1 (as by Watteau, La Boudeuse [Woman Sulking], lent by the Hermitage).

Valenciennes, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), cat. 43 (as by Watteau, La Boudeuse, lent by the Hermitage).

New Haven, Yale Center, Strawberry Hill (2009), 52-53, cat. 192 (as by Watteau, La Boudeuse [A Man and Woman Sitting], lent by the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, "Notes manuscrites," cat. 303.

Goncourt, Watteau (1875), cat. 114.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), no. 84.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs, 1: 102-03, 266; 3: cat. 303

Ernst, “L’Exposition de peinture française” (1928), 172.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 101.

Réau, “Catalogue de l’art français” (1929), 68.

Rey, Quelques satellites (1931), 89-90, 92.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 220

Sterling, Great French Paintings (1958), 212.

Hermitage cat. (1958), 290 (cat. 4120).

Paris, Orangerie, L’Art français et l’Europe (1958), 35.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Descargues, Le Musée de l’Hermitage (1961), 168.

Lewinson-Lessing, Meisterwerke (1963), no. 69.

Nemilova, Watteau and His Works (1964), 149-51, 186-87, no. 7.

Eidelberg, “Watteau Paintings in England” (1965), 581.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 116.

Eidelberg, "Watteau's 'La Boudeuse,'" (1969), 273-78.

Gubchevskiĭ, Hermitage: Painting (1970), pl. 43.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B24.

Zolotov, Watteau, catalogues raisonnés (1973), cat. 10.

Zolotov, Watteau (1973), 144-45, cat. 10.

Ingamells and Raines, “Catalogue of Mercier” (1976-78), cat. 289.

Raines, “Watteaus and ‘Watteaus’ in England” (1977), 51, 57, 59, 63.

Guerman, Antoine Watteau (1980), 52, 169-71, 183.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 163.

Nemilova, Peinture française (1982), cat. 51.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 111.

Zolotov, Watteau, peintures et dessins (1985), cat. 44.

Nemilova, Peintures francaise au XVIIIe siècle (1986), cat. 51.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 332.

Zolotov, Watteau (1996), cat. 16.

Hill, Walpole's Art Collection (1997), 43.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 44,

Dukelskaya and Moore, A Capital Collection (2002), 456.

Glorieux, "L’Angleterre et Watteau” (2006), 52-54.

Whedon, “Sensing Watteau” (2008), 118-19.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 195.

Eidelberg, "Mercier, Watteau's English Follower" (2013).

RELATED DRAWINGS

Only one small Watteau drawing can be associated with La Boudeuse, namely a study for the man now in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 332). This drawing, clearly trimmed on at least three sides, was undoubtedly part of a larger study in which more of the feather, the man’s right shoulder, and his torso were visible. The study might well have been on a sheet with other studies from the same model. This would explain the differences between the present drawing and the painted figure; the beret and feather are at a slightly different angle in the painting, and less of the left cheek is visible there. Watteau used the same man in the foreground of his Plaisirs d’amour in Dresden. There the beret is angled as in La Boudeuse, so too is the face, and the right arm is extended the same way as in La Boudeuse—even to the position of the extended thumb. These commonalities suggest what the full study of the man must have conveyed.

REMARKS

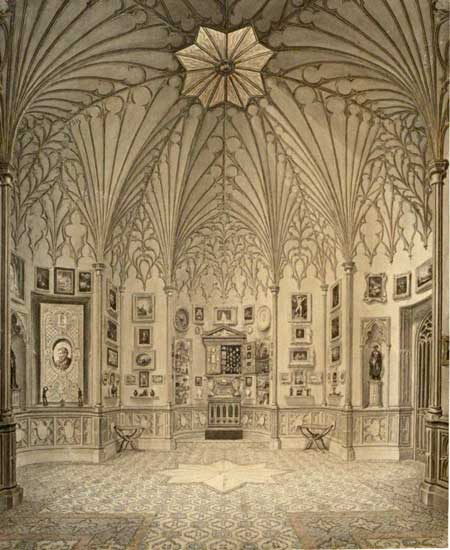

Because the painting was not recorded in Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé, and was either executed in England or went almost immediately from Paris to England, it essentially remained hidden from sight. Even though it probably hung in the home of the Prime Minister of England at 10 Downing Street or at his country home at Houghton Hall, it was not noted or commented upon. Likewise, even though it was displayed at Strawberry Hill for a century (see illustration below), it was still ignored until c.1842.

Mercier’s etching played a central role in the painting's history. An exemplar of this print was in the collection formed in the eighteenth century by Gilbert Paignon-Dijonval (1708-1792), and it was listed in the catalogue published in 1810 by M. Bénard, cat. 8090: "Bergers conduisant leurs troupeaux, et la boudeuse: 2 pièces en h. Ravenet et P.M. sc.” This reference was picked up by Edmond de Goncourt who, at best, knew only the Mercier etching, not the actual painting. The titles, once used by de Goncourt, soon became authoritative. La Boudeuse is a curious name since the woman portrayed is not actually pouting. The Russian scholars Dukelskaya, Gubchevskiy, Nemilova, and Zolotov prefer the title La Capriceuse, but this is not necessarily an improvement. Her head is lifted spiritedly, as though she is listening to a sound or to something being said—which is quite the opposite of pouting.

The painting sold from Gautier's collection in London in 1726 must have been La Boudeuse. The description of it as “a Man and Woman, sitting” may seem vague but it can be applied to very few other Watteau paintings. Alternative identifications of it such as Le Tête-à-tête (a work probably in France throughout the eighteenth century), or L’Amoureux timide and La Leçon de chant (pendant paintings that remained together and went to Spain), are unlikely. It also should be noted that of Gautier’s four other Watteau paintings, the “Venus with Nymphs at Sea” can be identified with another composition etched by Mercier.

Likewise, there can be no doubt that the painting traveling under the title La Conversation and sold from the collection of Horace Walpole was La Boudeuse. The picture was depicted in situ in the Tribune of Walpole’s home, hanging on a far wall just under the decorative ribs of the ceiling. Because Horace's painting came from his father’s collection, this establishes it was in England before 1745. It was not listed, however, in the 1736 inventory of Robert Walpole’s collection that Horace drew up; the manuscript is now in the collection of the Morgan Library & Museum.

La Boudeuse thus has one of the most continuous provenance listings for any Watteau painting, essentially from Gautier’s sale in 1726, only five years after Watteau’s death, until the present. Yet its position within Watteau’s oeuvre has not been secure. The turn against Watteau’s authorship began almost a century ago as a result of Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold’s research into Mercier’s etchings and their realization that some of them, such as Le Danceur aux castagnettes, were Mercier’s pastiches after Watteau. They wrongly concluded that La Boudeuse was another of Mercier’s creations. This idea was adopted by Adhémar, the cataloguers of the 1958 exhibition L'Art français et l'Europe, and as well by Macchia and Montagni. Although I published the painting’s notable provenance in 1969, and demonstrated Watteau’s authorship, some critics have remained dubious. These include Ingamells (1977), Saint-Paulien (as recorded by Ferré), and Posner, who proposed that it was a collaboration between Watteau and Mercier, with the latter artist responsible for the landscape. Nonetheless, the painting has been accepted by the majority of modern critics.

The date assigned to the painting has varied from author to author, as is true for all of Watteau’s paintings. Mathey, Roland Michel, Temperini, and Glorieux, among others, have dated it early, c. 1715, 1715-16, or 1715-17. Rosenberg preferred 1717 but dated the drawing of the man to c. 1715. Many critics, especially the Russians, have opted for 1718, and have suggested that the picture might have been painted when Watteau was in England, i.e., in 1719-20.