- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

La Cascade

Entered April 2017; revised December 2024.

Switzerland, private collection

Oil on panel

41 x 31.9 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

La Promenade dans le parc

RELATED PRINTS

Gerard Jean-Baptiste Scotin after Watteau, La Cascade, engraving, c. 1729.

Watteau’s La Cascade was engraved in reverse by Gerard Jean-Baptiste Scotin. The print was announced for sale in the March 1729 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 542).

PROVENANCE

Collection of Monsieur de Monmerqué. His ownership is noted on Scotin’s engraving of 1729: “du Cabinet de Mr de Monmerqué.” He cannot be the fermier génerale, who died in 1717, but probably was one of his sons. A possible candidate is Mathieu Monmerqué (d. 1749), “entrepreneur des tapisseries du Roi” at the Gobelins. If so, he might have known of Watteau and his paintings through Julienne, whose own tapestry works were there.

Paris, collection Poullain (Receveur général des domaines du Roi). His sale, Paris, March 15-21, 1780, lot 113: “ANTOINE WATEAU . . . Deux Tableaux faisant pendans.

L’on voit, dans l’un, l’Intérieur d’un Bois, & des masses de paysage. Sur le devant est un Berger Espagnol dansant avec une jeune Femme au son d’une vielle dont joue un homme assis, derrière lequel sont debout deux autres personnages, qui les regardent, un chien est couché auprès de la pannière & de la houlette. Un peu plus loin un Berger veut embrasser une Bergère assise sur l’herbe, qui le repousse; leurs troupeaux sont auprès d’eux.

Dans l’autre, est un Bosquet orné d’un bassin avec des cascades. Un Espagnol & une Femme debout s’entretiennent ensemble, pendant qu’un autre homme & une autre femme assis font la conversation; à leurs pieds est assis un cinquième personnage jouant de la guitarre. Haut. 16 pouc. Largeur 12 pouces. B.” Sold for 610 the pair to the dealer Langlier.Paris, collection of Barthélémy Henri Loliée (Lollier) (prosecutor in the Chambre des Comptes). His sale, Paris, April 6ff, 1789, lot 54: “A. Watteau . . . Deux petits Tableaux de forme ronde, représentant des amusements champêtres; dans l’un, on compte cinq figures, dont un homme & une femme écoutant un personage qui pince de la guitarre; dans l’autre on remarque un homme vêtu à l’Espagnole, qui danse avec une jeune dame. Ces deux Tableaux d’une touche spirituelle & de la plus riche couleur, ont toujours été considérés avec distinction. Ovale sur bois. Diametre 7 pouces 6 lig.” Bought for 501 livres by Defer.

Paris collection of Monsieur Lacaille. His sale, Paris, January 23ff, 1792, lot 56: “A. WATTEAU Deux petits tableaux de forme ronde, représentans des amusemens champêtres, un orné de sept figures, & l’autre de cinq sur des fonds de paysages, sur H. diametre 7 pou. B.” The paintings sold to [Guenard?] for 180 livres according to an annotated copy in the Frick Art Reference Library.

Paris and the Château de Moreuil, collection of Madame la Marquise de Plessis-Bellière (née de Pastoret). Her sale, Paris, May 10-11, 1897, lot 146: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) (Attribué à) . . . La Promenade dans le Parc. Une jeune femme, vêtue de satin blanc, converse avec un jeune homme qui la regarde en s’appuyant sur sa canne. A gauche, derrière un musicien jouant de la mandoline, deux personnages échangent de galants propos. A droite, une fontaine ornée de statues; à travers les grands arbres du parc, on aperçoit le ciel et un fond de paysage. T. — H., 0m, 42. L., 0m, 32. Ces deux tableaux [this painting and Danse paysanne], de forme primitivement ronde, ont été agrandis.” Sold for 8,400 livres to Michel H. Michel-Levy, according to an annotated copy of the catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorisches Documentatie. The claim that the de Plessis-Bellière paintings were on canvas is an error.

Paris, collection of Henri Michel-Levy (1844-1914; artist). His sale, Paris, May 12-13, 1919, lot 27: “WATTEAU (JEAN-ANTOINE) PENDANT DU PRECEDENT [La Danse paysanne] . . . La Cascade . . . Dans un parc, devant un basin circulaire orné d’une fontaine en pierre représentant des enfants avec une chèvre, montés sur une vasque dont le pied est formé de dauphins, un couple d’élégants personnages se promène. L’homme est en habit de soie de couleur puce, un manteau rouge drapé sur l’épaule. La jeune femme, coiffée d’un toquet rose à plumes bleues, est vêtue d’une robe de satin blanc. A gauche, un joueur de luth, étendu sur un tertre, et deux personnages à l’ombre des grands arbres. Bois. Haut., 42 cent.; larg., 32 cent. Cadre en bois sculpté. Gravé par Scotin. Collection du Plessis-Bellière, vente les 10-11 mai 1897, no 146 du catalogue, avec la mention attribué. Deux tableaux dont la description s’applique à la Danse paysanne et à la Cascade, ont figuré à la vente Poullain, 15 mars 1780, no 113 du catalogue. On remarque que le centre de ces deux compositions est inscrit dans un panneau rond qui paraît avoir été encastré dans des panneaux plus grands, pour permettre à l’artiste de donner plus d’ampleur à sa composition.”

Paris, collection of H. Meyer.

Zurich, sale, Galerie Koller, May 16-17, 1980, lot 5182: “WATTEAU, ANTOINE . . . “La Cascade”. Um 1715. Öl auf Holz. 43x32,5. (130 000.- / 150 000.-) Bestätigung von Alexandre Ananoff. Provienz: Coll. M. de Monmerqué; Coll. Poullain (Versteigerung Paris, 15. März 1780, Nr. 113; Coll. Plessis-Bellière (Versteigerung 10. Mai 1897; Coll. H. Michel-Lévy (Versteigerung 12. Mai 1919, Nr.27; Coll. Meyer. Literatur: Adhémar & Huyghe, Paris, Watteau, Nr. 57; André Chastel and Jacques Thullier, 1970, Tout l’oeuvre peint de Watteau, Nr. 113. TAFEL 14.” Reputedly bought by a Swiss private collector.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, ”Watteau” (1845), cat. 114.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 115.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 115.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 102, 259, 268; 3: cat. 28.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 81.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 116.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

London, Wallace Collection, Pictures and Drawings (1968), cat. P395.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 133.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 186, 229, 273.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 121.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 102, 415, 429, 532, R298.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 56.

Michel, Le «Célèbre Watteau» (2008), 204-07.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Drawings are associated with several of the figures in La Cascade, most notably the principal couple.

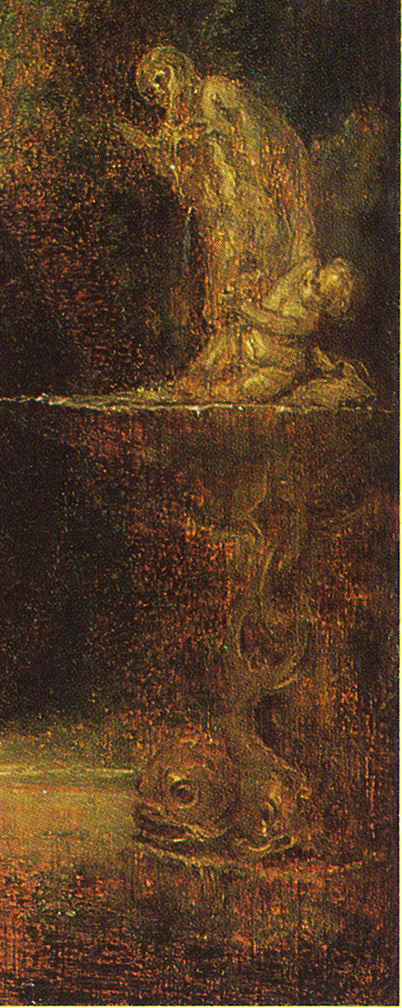

Watteau, La Cascade (detail).

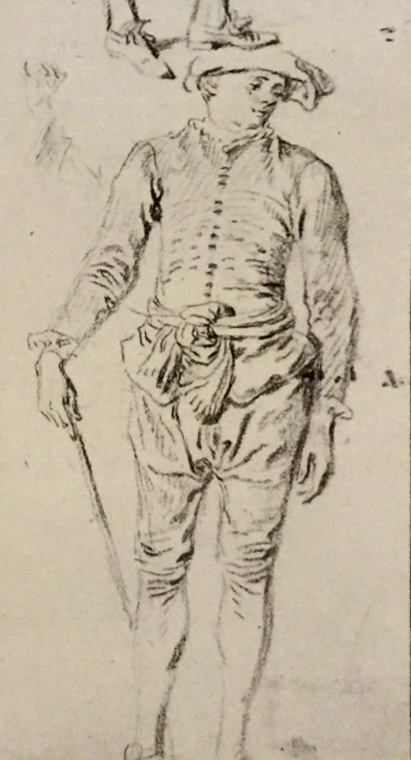

Watteau, Studies of Six Men (detail), red chalk. Haarlem, Teylers Museum.

The gentleman dressed in theatrical garb who has stopped and turns to the woman he is escorting, is based on a figure study on an early Watteau sheet in the Teylers Museum, Haarlem (Rosenberg and Prat 102). Although Watteau transferred most details of his costume into the painting, he exchanged the hat for a more fanciful one.

The elegantly posed woman was based on a lightly drawn study (Rosenberg and Prat R298). Although she is bareheaded in the drawing, and her facial features are minimally blocked in, the details of her costume correspond exactly to what we see in the painting. This drawing is very small, especially in its width, prompting one to imagine that originally it was on a wider sheet, probably alongside other studies of the same model, drawn less schematically and with greater detail. This, after all, was standard practice for Watteau and most draftsmen.

Watteau, Three Studies of Men, red chalk, 17.3 x 22.8 cm. London, British Museum.

For example, we might consider a sheet with a set of three studies of men by Watteau, now in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 130). There the rightmost figure is a fully finished rendering, the leftmost is slightly less full, and the middle one is drawn very lightly, much like the study of the woman used for La Cascade.

It was perhaps the brevity of draftsmanship that prompted Rosenberg and Prat to reject this study, a drawing that otherwise has not been questioned before. It makes little sense to reject the drawing. If it were not autograph, how can one explain it—as a copy from the engraving after the painting? And why would the copyist have omitted her hat? A curious feature is that this study is in the opposite direction to the painting, yet that often occurs in Watteau’s oeuvre.

It has been proposed that the woman standing at the left side of the painting is based on a study of a seated woman in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 532). However, such an association is tenuous at best. While the tilt of their heads and their profils perdus are similar, their costumes differ significantly: the arrangement of ribbons in their coiffure differs, and the woman in the drawing sports a scarf around her neck whereas the woman in the painting has a ruff.

The fountain at the right of the painting—from which the painting’s title was derived—is composed of two separate elements. At the top is a sculptural group of putti playing with a goat, and this group is based upon an actual work by Jacques Sarazin that was in Pierre Crozat’s collection. Watteau drew this group several times, probably executing more than the three studies still extant. The study at the right side of a sheet in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 429) was used for La Cascade. It is presumed that these studies of Sarazin’s sculpture were made in 1715 or thereafter, once Watteau was living under Crozat’s roof. Different views of the same sculpture appear in other mature Watteau paintings, namely the Amusements champêtres and La Famille. As Watteau’s drawings show, he must have known not the Sarazin group now in the Louvre but a similar one with a different arrangement of putti. Even if we cannot pinpoint the specific Sarazin group that Crozat owned, we can be sure that it was not posed on a sea shell supported by a trio of dolphns with intertwined tails. Such slender elements could not have sustained the weight of the marble goat and putti.

REMARKS

From their creation until almost a hundred years ago, La Cascade and its pendant, La Danse paysanne, remained together. However, we cannot follow their common history closely. We know where they were in the very early eighteenth century—when they were in Monmerqué’s collection—but then we lose sight of them until 1780, and subsequently they disappeared from sight again until a few years before the end of the nineteenth century.

A dramatic physical change occurred to the two panels during the course of the eighteenth century. Although they began as vertical rectangles, at some point they were cut down into small circles, only about half the size of the original panels. This change was noted when they were sold in 1780 from Poulain’s collection. The change in shape was also recorded by Charles Henri Watelet (1718-1786), who engraved La Danse paysanne in a circular format prior to c. 1785. The two paintings were again described as circular when they were sold in 1792 from the Lacaille collection.

Another change occurred in the nineteenth century when they were restored to their original rectangular format. Some collector or dealer set the circular portions back into rectangular panels, which were painted to duplicate the discarded landscapes, landscapes that were recorded in the Julienne engravings. Their restored condition as rectangles was first recorded in 1897 when the paintings were sold from the collection of the Marquise de Plessis-Bellière. The restoration was not announced but it is evident in the measurements that were cited in 1919, when the paintings were sold from the esteemed Michel-Lévy collection. The only critic to reject this narrative was Roland Michel. She inverted the chain of events, claiming that they were originally round paintings but were engraved as rectangles, which were “Later inserted into rectangular canvases [sic for panels].” However, while Watteau painted many oval paintings and some of them were misleadingly engraved as rectangles (such as Le Rendez-vous, L’Alte, and Le Défilé), the artist never employed a circular format. The oval was a preferred format in the eighteenth century, as Roland Michel admirably proved in her 1975 exhibition, Éloge de l’ovale.

The peregrinations of La Cascade in the twentieth century are not clear, except that the two paintings were soon separated after the 1919 sale of Michael Michel-Lévy’s collection. H. Meyer of Paris acquired La Cascade. In 1950 Adhémar wrote that La Cascade was in a private Paris collection, presumably referring to Meyer’s collection. Going its separate way, La Danse paysanne entered the collection of Alwin Schmid in Switzerland before February 1926. Macchia and Montagni unfortunately jumbled all the data. wrongly claiming that the two paintings were together in the Léon Michel-Lévy sale on June 17-18, 1926, and then were bought by H. Meyer of Paris. But neither painting was in the 1926 sale, and Danse paysanne had already gone to Switzerland.

When La Cascade appeared at auction in 1980, it could be seen clearly for the first time, and it is evident that it has suffered, more so than the pendant Danse paysanne in the Huntington Library. The original circular portion from Watteau’s hand has been heavily overpainted, so that none of the magic of his figures is still visible. Equally distressing is the condition of the surrounding rectangular portion, even though it is a nineteenth-century replacement. The area around the fountain has been abraded, and the trees and foliage are overpainted.

Little attention has been paid to how La Cascade fits into Watteau’s oeuvre. It is not an early work, nor is it a fully mature work from his last years. But placing it in the middle of his career poses problems because the temporal boundaries are so vague. Mathey proposed 1713 as its date, which is surely too early. Macchia and Montagni opined that it was no earlier than 1715 because of the artist’s reference to Sarazin’s sculpture of the goat and putti—a work he would have seen after he began staying with Crozat in 1715—whereas Rosenberg and Prat suggested a date earlier than 1715-16. Adhémar dated it to somewhere between the spring and autumn of 1716, a short span in which she unreasonably proposed to squeeze fifty paintings. Temperini proposed c. 1716-17. In short, this is another instance of the divergence of opinions regarding Watteau’s chronology.

For copies of La Cascade CLICK HERE