- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Chat malade

Entered October 2017; revised July 2021

Presumed Lost

Materials unknown

Measurements unknown

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

La visita al gatto

RELATED PRINTS

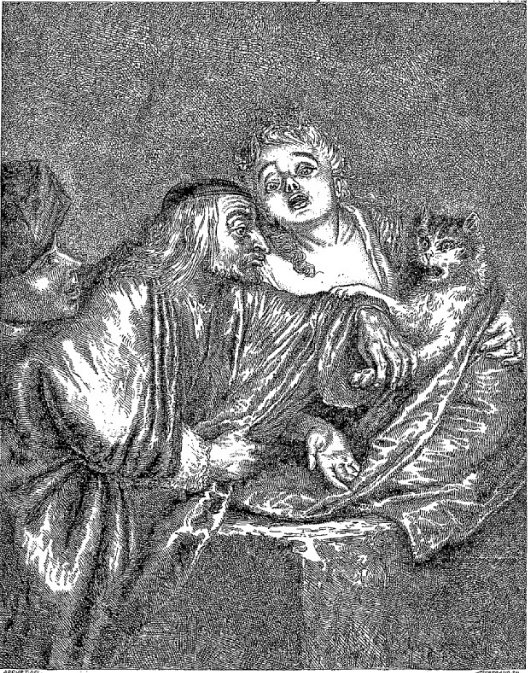

Jean Etienne Liotard after Antoine Watteau, Le Chat malade, 1731, engraving.

Le Chat malade was engraved in 1731 by Jean Etienne Liotard (1702-1789) for Jean de Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé. It was announced for sale in the September 1731 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2209).

Boucart after Jean Etienne Liotard, Le Chat malade, 1857.

A print after Liotard’s engraving, in the same direction as the original engraving, was commissioned for the January 1857 issue of Le Magasin pittoresque.

PROVENANCE

The ownership of the painting at the time of Liotard’s engraving was not announced, and no trace of it has been found in eighteenth-century sales.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” vol. 9, fol. 197.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 59.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 39.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 93.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 259; 3: cat. 32.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 180.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), 47 and note 46, cat. 82.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 108.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B 98.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 254.

Foucart-Walter and Rosenberg, Le Chat et la palette (1987), 26.

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard (2008), 153, 239-41, 253.

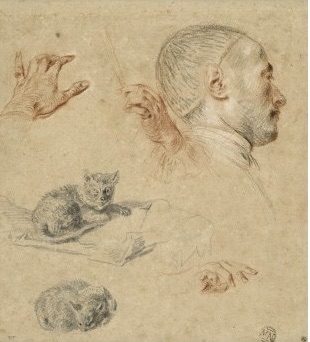

RELATED DRAWINGS

No drawings have been specifically related to Le Chat malade, although some scholars have cited Watteau’s gouache and chalk studies of cats. For example, Adhémar cited Watteau's gouache studies of cats sold from the collection of Charles Antoine Coypel. Although a number of Watteau's drawings of cats have survived (e.g. Rosenberg and Prat 315, 613, 614), those gentle pets do not resemble the strangely demonic one in Le Chat malade.

REMARKS

The subject of the painting is enigmatic. The poem beneath Liotard’s image, commissioned after Watteau’s death, is not that illuminating, even in translation. More concerned with clever rhymes than with interpreting Watteau’s picture, the poet only added to the complexity of the issue.

Iris idolatre Minet Quoique de tous les Chats Minet soit le plus traitre; Vous voyez avec joye un amant au trepas, Tableau de l'humaine folie |

Iris Idolizes Puss Although, of all cats, Puss is the most treacherous; You joyfully see a lover until death A picture of human folly. |

Mariette described the painting in more precise terms: “Un sujet grotesque, représentant un médecin qui tâte le pouls à un chat malade.” In essence, a woman is holding a cat in a large cloth and a man holds one of the animal’s legs. A boy at the right looks on intently. The cat’s expression seems to be one of fright and anger.

But is this a genre scene or does it represent a theatrical subject? While not certain, it seems to belong to the world of the theater. The man’s skull cap, ample cape, and small beard are not found in contemporary French masculine attire. Instead they are the trademarks of Scaramouche, one of the stock characters in the commedia dell’arte. Two prints by Nicolas Bonnart (1637-1717) show this actor with his customary garb and facial hair. In one print he wears his typical beret, but in the other he has taken it off and reveals the skull cap beneath it. What scene in what play did Watteau represent and what did he intend viewers to understand? These questions remain unanswered.

François Boucher, Woman with a Cat, c. 1732, oil on canvas, 81.5 x 65.6 cm. New Orleans, Museum of Art.

There are a number of Dutch and French paintings and engravings with the theme of young women with startled or malevolent cats. For example, a painting by Boucher, executed little more than a decade after Watteau’s death, conveys a different, charmingly erotic mood. A woman in bed, in a provocative state of undress, has been playing with her cat when a handsome young suitor pulls back the drapery. Both the woman and the cat seem startled. When engraved, a short explanatory poem instructed the viewer: “Beware of the cat’s treacherous paw; it is like love, whose flattery can take a nasty turn and harm you.” One might wonder if Watteau’s scene turned on this or a related theme, but which he treated in the broad manner of the commedia dell’arte.

Although Watteau’s original painting has not survived, scholars have attempted to assign it a date and, as always, there has been considerable divergence of opinions. Adhémar proposed 1712; Mathey placed it c. 1713-15; Huyghe dates it very late, c. 1717-18.

For copies of Le Chat malade, CLICK HERE