- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Les Comédiens français

Entered April 2019; revised July 2021

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jules Bache Collection, inv. 49.7.54

Oil on canvas

57.2 x 73 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Comédiens françois

Französische Schauspieler

The French Comedians

Représentation d’une tragédie

Teatranti francesi

RELATED PRINTS

Jean Michel Liotard after Watteau, Les Comédiens français, 1731, engraving.

Watteau’s painting was engraved in the same direction for Jean de Julienne's Oeuvre gravé by Jean Michel Liotard. It was announced for sale in the December 1731 issue of Le Mercure de France (p. 3091).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). Jullienne’s ownership was acknowledged in the caption of Liotard’s print: “Du Cabinet de M. de Jullienne.” It was sold before the illustrated catalogue of his collection was prepared c. 1756; the catalogue is now in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

Potsdam, collection of Frederick the Great (1712-1786; King of Prussia). It was in the Royal Palace in Potsdam, probably from about 1746, but definitely by 1756. It remained with the Prussian royal family in the Alte Schloss, Berlin, and then was transferred to the Neue Palais in Potsdam where it remained until 1888.

Berlin, collection of Kaiser Wilhelm (1888–1927; King of Prussia). After the Kaiser abdicated in 1918 and took refuge in Doorn, The Netherlands, the picture remained in Germany. An account that the Kaiser liked this picture so much that he carried it under his arm to the Netherlands is patently false since it remained in Germany.

Berlin, with Hugo Moser (1881-1972; dealer). Sold to Baron Joseph Duveen, c. 1920.

New York, Paris, London, with Joseph Duveen (1869-1939; dealer). The painting was sold to Jules S. Bache for $275,000.

New York, collection of Jules S. Bache (1861-1944; banker); donated by his estate to the Metropolitan Museum in 1949.

EXHIBITIONS

Berlin, Königliche Akademie, Gemälden älterer Meister im Berliner Privatbesitz (1883, cat. 8 [ref. Dohme 1883 and Rosenberg 1984]).

Berlin, Königliche Akademie, Werken französischer Kunst (1910), cat. 88 (Watteau, Französische Komödianten, im besitz Seiner Majestät des Kaisers und Königs).

London, 25 Park Lane, Three French Reigns (1933), cat. 45 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by Jules S. Bache).

San Francisco, Palace of the Legion of Honor, French Painting (1934), cat. 58 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by Jules S. Bache, New York).

Paris. Bibliothèque nationale, Troisième centenaire (1935), cat. 949 (Watteau, Les Comédiens français, lent by Jules S. Bache, New York).

Copenhagen, Charlottenborg, L'art français au XVIIIe siècle (1935), cat. 261 (Watteau, Les Comédiens français, lent by Jules S. Bache, New York).

Paris, Palais national, Chefs d'œuvre de l'art français (1937), cat. 230 (Watteau, Les Comédiens français, lent by Jules S. Bache, New York).

New York, World's Fair, Masterpieces of Art (1939), no. 406 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by Jules S. Bache, New York).

New York, World's Fair, Masterpieces of Art (1940), cat. 212 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by Bache Collection, New York).

New York, Parke-Bernet, French and English Art Treasures (1942), cat. 68 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by the Jules S. Bache Collection, New York).

New York, Metropolitan Museum, Bache Collection (1944), cat. 54 (Watteau, The French Comedians).

Philadelphia Museum, Diamond Jubilee Exhibition (1950), cat. 50 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Meisterwerke aus den Sclössern Freiderichs des Grossen (1962), cat. 144 (Watteau, Les Comédiens français, lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau, 1684–1721 (1984), cat. 70 (Watteau, The French Comedians, lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Munich, Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Friedrich der Grosse (1993), cat. 84 (Watteau, Die französischen Komödianten, lent by the Metropolitan Museum, the Jules Bache Collection, New York).

Martigny, Fondation Gianadda, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2006), cat. 33 (Watteau, Les Comédiens-français / The French Comedians, lent by the Jules Bache Collection, New York).

New York, Metropolitan Museum, Watteau, Music, and Theater (2009), cat. 14 (Watteau, French Comedian, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Jules S. Bache Collection, New York).

Versailles, Château, Fêtes & Divertissements (2016), cat. 63 (Watteau, French Comedian, Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Jules S. Bache Collection, New York).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau,” (1845), cat. 73.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 74.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 64.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures théatrales” (1904), 148-49.

Dacier, Le Musée de la Comédie-Française (1905), 47-48.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), no. 101.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 65; 3, cat. 205.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 53.

Bache, A Catalogue of Paintings (1939) cat. 55.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 212.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 69.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 206.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B 22.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 245.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 179, 266.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 9-10, 266.

Baetjer, European Paintings (1995), 368.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996)

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 129, cat. 110.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 145-46.

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard (2008), 722-23.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 344.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. A4.

Paris, Jacquemart-André, Watteau à Fragonard (2014), under cat. 26.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Only one Watteau drawing is directly associated with Les Comédiens français, is a study of the face of the principal actor (Rosenberg and Prat 155 verso). It and another in New York (Rosenberg and Prat 640) which depicts the same otherwise unidentified person in profile, suggesting that the characters in the painting may be specific actors, even if their identities are not agreed upon. On the other hand, a drawing of a very similar man’s head in Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 487) was used for the Louvre Pélerinage à Cythère, a painting without specific actors.

It has also been suggested that the head of Raimond Poisson as Crispin on a sheet of studies in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 569) is related to the character in the Metropolitan Museum painting. However, the head of Crispin in the London drawing is not convincing as a source for the painting, certainly not in specific features—the tilt of the head, the direction of the glance—or overall characterization.

REMARKS

Given the vicissitudes that most Watteau paintings have endured, Les Comédiens français is in remarkably good condition. In the 1870s, Dohme, keeper of the paintings in Berlin, wrote to Edmond de Goncourt and described how the costumes were sketchily rendered and poorly restored: “seulement esquissé dans les étoffes et malheureusement assez mal restauré.” Alfassa’s declared that the face of the principal actor was entirely repainted but that seems exaggerated. No such repaint is visible today. On the other hand, the fountain and shrubbery at the right do appear overpainted. The painted surface is thin in places, especially in the background towards the center, where elements of an alternate architectural scheme are visible to the naked eye. It seems that a full conservation study should be undertaken.

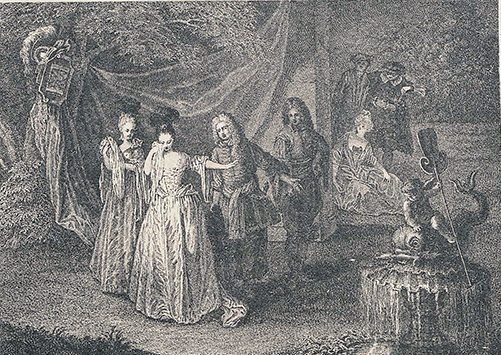

Whereas the engraving records the painting’s measurements as 59.4 x 85.6 cm, the actual canvas measures only 57.2 x 73 cm. It is evident that the painting has been trimmed severely along the upper and lower edges. This can be seen by comparing the actual painting with Liotard’s engraving. Originally, the arches were more complete, there was a greater expanse of tiled floor in the foreground, and the fountain was not cut by the frame.

Despite the almost universal acceptance of the painting, there have been a few dissenting voices. While agreeing to Watteau’s authorship, Christian Michel proposed that the architectural setting might have been painted by Michel Boyer. On occasion Watteau did collaborate with Boyer, but Boyer’s deep architectural perspectives have nothing in common with what we see in the Metropolitan Museum painting. Ferré, ever the erratic naysayer, catalogued Comédiens français in his “B” category, that is, paintings only attributed to Watteau, rather than in his “A” category of authentic paintings. He went so far as to propose that the painting was begun by Antoine Coypel and was finished by his son Charles Antoine—a theory that subsequent scholars have rightly ignored.

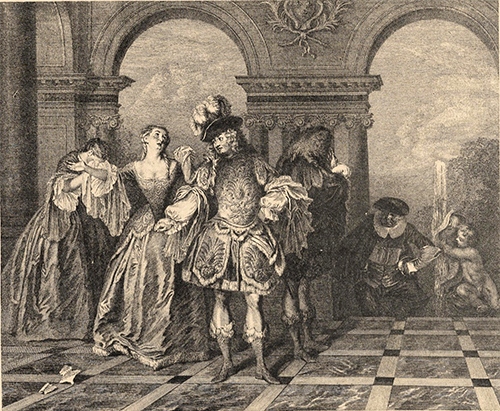

As with so many of Watteau’s inventions, the subject of his painting is much debated. The narrative is clearly theatrical. The heroine has received a note which causes her to declaim emotionally. Presumably it is news of a lover’s deceit, departure, or death. Her exaggerated gesture to the heavens is grandiose, and her servant cries in an equally histrionic manner. A similar pairing of a distraught mistress and a weeping servant appears in an early Watteau drawing, one that reflects his stay with Gillot (Rosenberg and Prat 114). This is not to imply that Watteau turned to this drawing but, rather, that these characters and gestures were standard elements in the Paris theater, ones that Watteau knew. So too, the actress's gestures and emotions in the drawing and in the painting are countered by a male actor who also gestures with outstretched arms. Although the costumes in the drawing strike an exotic, Oriental note, while the setting of the Metropolitan Museum’s painting suggests a Roman milieu, still the drawing and the painting have much in common.

At the right, climbing stairs hidden from our view, is the character Crispin—a role made popular by Paul Poisson. The inexplicable entrance of this beloved commedia dell’arte actor into an otherwise serious scene strikes a comic note in itself. This intrusion was well summed up when Liotard’s engraving was announced for sale in 1731, just a decade after Watteau’s death: it was described as “représentant une Tragi-Comédie.” Blanc has proposed that the scene of Crispin mounting the stairs and interrupting the drama represents the then-reigning habit in the French theater of offering a parody of the tragedy after the main drama had been played. It is an intriguing thought.

Watteau, Les Comédiens français.

Pierre Dupin after Watteau, Spectacle français, engraving (reversed to the original direction of the painting).

Apropos of the Comédiens français, Dohme was struck by what he saw as Watteau’s unique attempt to represent an actual stage performance, overlooking the artist’s earlier paintings such as Qu’ai-je fait, assassins maudits? and Spectacle français. The latter painting has sometimes been mentioned in relation to the Metropolitan Museum’s picture but with insufficient emphasis. Indeed, all the essential elements of Les Comédiens français are found in this lost early composition, in approximately the same order: at the left, the weeping female servant, then the heroine, the hero, Matamore, and somewhat in the distance, Crispin. Both compositions show a fountain at the right.

The palpability of the stage setting in Les Comédiens français, as well as the seeming verisimilitude of the characters, is so strong that it was only natural for scholars to have tried to identify the specific play being performed and name of the specific actors and actresses. The scholarship on these issues is a complicated history of assertions and opinions. Dacier, and then Dacier and Vuaflart, claimed that Watteau was representing a scene from Molière’s comedy Dépit amoureux. They claimed that was the only French play of the period where letters are thrown on the ground (in act 4, scene 3, Eraste and Jean tear up letters from each other). However, Florisoone noted that there are other plays in which handkerchiefs are cast on the ground, including scenes from Bérénice, Andromaque, and Phèdra. Nonetheless, the association with Molière was repeated in the following years by Mathey and Barker, and after the war by Adhémar as well as Montagni and Macchia.

Different arguments arose later when the painting was exhibited at the Académie française; it was proposed that Watteau was representing Racine’s drama Andromaque. This was reiterated several times, especially in the various catalogues of the Bache collection issued in the 1930s. Perhaps the most specific interpretation is the one offered by Blanc in 1970. He proposed that Watteau represented act 5, scene 5, of Racine’s Bérénice where Titus reads a farewell letter from the heroine. Only occasionally, as in the 2016 exhibition at Versailles, does the reference to Bérénice reappear. Several leading scholars, including Rosenberg and Roland Michel, have surrendered to the idea that Watteau’s subject is too ambiguous to be identified.

But even those who disagree about the identity of the play do agree that the three figures at the left represent the heroine, the hero, and the confidant, while at the right are Matamore and Crispin, characters representing Tragedy and Comedy respectively.

In a similar way, the identities of the actors and actresses have been debated for more than a century. Staley summed up the old tradition: “Very interesting as containing portraits of famous actors of the time.” Yet the only figure in Watteau’s painting whose identity remains assured is that of Crispin, whose visage was memorialized in Gaspar Netscher’s portrait of the actor. Louis de Fourcaud saw in the heroine a likeness of the actress Duclos, whose features were captured later in her life by Largillière; in that portrait, now in the Musée de la Comédie Francaise, her features are more mature and she is heavier; it is difficult to be sure if there is a visual relationship with Watteau's depiction. Since at least 1929, the actor has been identified as Pierre Tronchin de Beaubourg (c. 1662-1725). This identification rests on the authority of a M. Couet (or Cornet or Conet), librarian of the Comédie Française. It has not been challenged by competing theories but, also, it has not been corroborated. It is noteworthy that Rosenberg and Prat make no effort to identify the actor in the preliminary drawing.

The date of the painting is another disputed matter, although no more so than Watteau’s other paintings. While early on some thought it was painted around 1715, opinion has shifted to the last years of Watteau’s career. Alfassa proposed a surprisingly early date, to the first years of the artist’s stay with Crozat. When Bache exhibited the painting in 1937, a date of 1715-16 was offered. Schefer proposed a time between 1715 and 1719. Mathey dated it slightly later, c. 1717-21. Montagni and Macchia proposed that it was painted over a long period from 1717 to 1721. Dohme and Ephrussi had already edged toward a later date, between 1718 and 1720. Brookner, Posner, Roland Michel, Rosenberg and Prat, and Vogtherr dated it to c. 1720. Adhémar preferred c. 1720-21. Certainly the monumentality of the figures speaks in favor of a late dating. Unlike their counterparts in the earlier Spectacle français, the actors in this painting dominate the picture plane. So imposing that they almost seem larger than the arches behind them,. Their scale calls to mind the figures in L’Enseigne de Gersaint and Gilles.

For a while various critics believed that Les Comédiens français was painted as a pendant to Les Comédiens italiens, a picture that Watteau painted while in London in 1720. This theory began at least by the time of Phillips’ publication of 1895, and was supported by Brookner and Eisler, but has since been rejected by Posner and others. Indeed, their measurements and their provenances differ, and their compositional formats differ considerably. There is little reason to think that they were paired.