- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

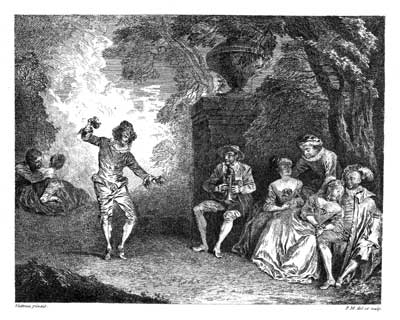

X. Le Danseur aux castagnettes

Entered March 2016; revised April 2016

Williams College Museum, Williamstown, MA, inv. 80.17.3, gift of C. A. Wimpfheimer

Oil on canvas

34.3 x 43.3 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Une compagnie de dames & de cavaliers

Danse aux castagnettes

Fête champêtre

Le Joueur aux castagnettes

RELATED PRINTS

Philippe Mercier, Le Danseur aux castagnettes, 28.4 x 35.9 cm. London, The British Museum.

The composition was etched in reverse by Philippe Mercier in 1723. The caption declares “Vatteau pinxit.” at the left and “P.M. del. et sculp.” at the right. The date of the etching was specified by Mariette in his Notes Manuscrites, fol. 192. When Mercier made the etching, he introduced certain changes, such as the dark hillock in the foreground that helps create a repoussoir effect. Also the indications of tree trunks, branches, and foliage in the etching do not correspond exactly to those in the painting.

PROVENANCE

London, collection of Admiral Sir George Seymour (1787-1870); by descent to his daughter Laura Williamina Seymour).

London, collection of Princess Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (née Seymour) (1832-1912); sold prior to her death.

Paris, with Gimpel & Wildenstein; sold c. May 1912 to Samuel Reading Bertron, Jr. for 220,000 francs (appx. $45,000). I am indebted to Dr. Diana Kostyrko for this data.

New York, collection of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Reading Bertron, Jr. (1865-1938; lawyer and banker); because Bertron had never actually paid for the picture and due to his economic reversals, Bertron consigned it back to Gimpel in 1921.

Paris, with René Gimpel; sold to Charles Anthony and Annie Wimpfheimer in December 1923.

New York, collection of Charles Anthony Wimpfheimer (1858-1934; velvet merchant) and Annie C. Wimpfheimer (née Nordlinger); by descent to their son Harold D. Wimpfheimer.

New York, collection of Harold D. Wimpfheimer (1896-1978; publisher) and Florence Wimpfheimer (née Selwyn); by descent to their son Charles Anthony Wimpfheimer (known as C. A. Wimpfheimer).

New York, collection of C. A. Wimpfheimer (b. 1928; publisher) and Ann Wimpfheimer (née Rosenfeld); donated to the Williamstown Museum in 1980.

EXHIBITIONS

New York, Altman Gallery, Loan Exhibition of Fifty-nine Masterpieces (1920),cat. 55 (by Watteau, Le Danseur aux Castagnettes, lent by Mrs. S. R. Bertron).

New York, Metropolitan Museum, Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition (1920), 10 (by Watteau, Fête Champêtre, lent by Mr. and Mrs. S. R. Bertron).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 107.

Goncourt, Watteau (1875), cat. 126.

Portalis, Les Graveurs (1882), 3: 82.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 68.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures galantes” (1904), 347.

“A Magnificent Loan Exhibition” (1915).

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 3: cat. 307.

Paris, Gimpel, Collection René Gimpel (1924), pl. 12.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 109.

Edwards, “Mercier’s Music Party” (1948), 328.

Cecil, “Remainder of the Hertford and Wallace Collections” (1950), 171.

Machell, “Remainder of the Hertford and Wallace Collections” (1950), 238.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 224.

Waterhouse, “English Painting and France” (1952), 127.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 42, 68, 77.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 120.

Raines and Ingamells, Mercier 1689-1760 (1969), under cat. 8.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B40.

Cailleux, “A Strange Monument” (1975), 246.

Ingamells and Raines, “Catalogue of Mercier” (1976-78), under cat. 291.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984) under cat. P24.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), under cat. 98, 102, 195.

Glorieux, “L’Angleterre et Watteau” (2006), 73.

Gimpel, Journal d’un collectioneur (2011), 451.

Eidelberg, “Mercier, Watteau’s English Follower” (2013).

REMARKS

Whereas Hédouin entitled the picture Danse aux castagnettes, Goncourt modified it to Le Danseur aux castagnettes. This became its standard title.

The early whereabouts of the painting are moot. Edmond de Goncourt tried to relate the painting to one sold in Paris in 1787. He misidentified the sale date as January 31, 1787, whereas the sale he was referring to transpired on March 20ff, 1787. In the latter sale, lot 202, was a painting attributed to Watteau and which was described as “Un sujet champêtre dans un paysage agréable, on y compte sept figures d’hommes & femmes, dont un jeune homme dansant devant les autres personages.” However, there are eight figures in Le Danseur aux castagnettes, not seven (unless one does not count the dancer). Also the Williamstown painting is on canvas, whereas the one sold in 1787 was on panel. Not least, the measurements of the actual painting (34.3 x 43.3 cm) differ from the one sold in 1787, especially in terms of width (36.8 x 59.7). These many differences suggest that the 1787 painting was a different composition, perhaps one actually by Watteau and his circle. Finally, since Mercier likely painted his picture in London and Admiral Seymour undoubtedly came into possession of the painting in London, it is unlikely that it would have passed in a Paris sale in 1787.

Glorieux proposed associating Le Danseur aux castagnettes with a painting attributed to Watteau that was sold in London at Christies on March 8-9, 1771, lot 72: “A Spanish concert: The coulouring transparent, florid, and glowing; highly finished and highly preserved.” However, that painting was measured at 10 x 12 inches (25.4 x 30.5 cm), which is considerably smaller than the Williamstown College picture, and the term “Spanish” probably referred only to the costumes, not to the presence of castanets.

It has not been possible to identify Le Danseur aux catagnettes with any of the many fêtes galantes sold in England in the nineteenth century but this is to be expected, given the brevity of the descriptions in most English catalogues, the frequent lack of measurements, and the lack of a fixed name for the painting. The first known owner was probably Admiral Sir George Seymour. As he was the youngest brother of the second Marquess of Hertford, some, such as Gimpel and Cecil, presumed that Lord Hertford had once owned this painting. However, this was contested in 1950 by Valda Machell (Countess Victoria Alice Leopoldina Alda Laura), daughter of Princess Victor of Hohenlohe-Langenburg and granddaughter of Admiral Seymour.

While it was with the Seymour family, the painting was believed to be by Watteau, and this attribution remained in place in the Watteau literature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was thought justified by Mercier’s etching that proclaimed “Vatteau pinxit.” Things changed in 1950 when Adhémar listed the painting under Mercier’s name. Although less than a decade later Mathey tried to restore the attribution to Watteau, the tide of opinion had begun to flow in the opposite direction, against Watteau. Ferré, writing through the voices of his colleagues, rejected the attribution to Watteau and accepted Adhémar’s opinion that it was by Mercier. In 1984 Rosenberg classified the painting as a being of uncertain attribution, and even more surprisingly, a decade later Rosenberg and Prat described the Mercier etching as being after Watteau. Understandably, Posner and Roland Michel did not mention the painting, nor did Temperini include it in his brief catalogue of Watteau’s oeuvre.

Curiously, in their catalogue raisonné of Mercier’s paintings, Ingamells and Raines listed the etching and repeated an old claim that there were two paintings with this composition, one in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg (an old mistake) and one in New York (the painting now at Williams College). Of the latter, they wrote, “the attribution to Watteau is doubted by Adhémar who suggests Mercier.” Not only do they not explicitly accept Adhémar’s reattribution but they tellingly did not provide a separate entry for the painting, thus implying that they did not accept that it was by Mercier. On the other hand, I have in the past argued that the painting it central to Mercier’s early oeuvre.

Indeed, the Williamstown College painting exhibits all those qualities one would expect from Mercier. Its mannerisms closely match those of the etching, which is not surprising since they come from the same hand. The dulled, expressionless faces and the awkwardly proportioned bodies, with heads too large for the bodies that support them, are characteristic of Mercier. (Although this was especially true of the seated man at left, this figure is presently highly overpainted.) Perhaps the most successful part of the painting, the part that most closely emulates Watteau, is the landscape and, as can be seen in Mercier’s L’Heureuse rencontre, this is an area where he often best emulated his master.

While the Williamstown College painting was not executed by Watteau, many of its figures were derived from his early compositions. The single most important source of inspiration is Watteau’s Le Bal champêtre, a painting that Mercier knew firsthand. As I have previously shown, one of Mercier’s early drawings is a compositional study that copies the group of standing figures at the right side of this same painting. Most importantly, Le Bal champêtre inspired the general theme of a group of figures looking on at a central dancer posed in a graceful dance step and keeping rhythm with a pair of castanets. Although Mercier reversed Watteau’s figure, still he maintained the exact pose and costume. While reducing the number of musicians from three to one, still, Mercier copied Watteau’s bagpiper with relative fidelity. He retained the general pose and costume, but turned the head a bit more frontally.

As previously demonstrated, Watteau’s Les Comédiens sur le champ de foire, now in Berlin, provided the basis for the four figures at the left of Mercier’s painting. In both instances a woman leans to the side, the weight of her upper body resting on her arm that is posed in her male companion’s lap. Her other arm is posed across her lap. To the side of them, a standing man leans forward over a seated woman, his arms reach toward her and her left arm rests across her lap. There are, of course, differences between the two versions. Mercier has changed the position of the seated man’s legs, splaying them awkwardly. Also this man now dully stares outward, a bit strangely, rather than looking across and into the painting. So, too, the upward glance of the seated woman at the right has been modified so that she does not look at her attendant male.

X. Le Danseur aux castagnettes (copy 1)

Entered March 2016

Whereabouts unknown

Materials unknown

Measurements unknown

PROVENANCE

Paris, private collection. The photo on file at the Service de documentation, Département des peintures, Musée du Louvre, was taken by a Parisian photographer, Mark Vaux, which presupposes that the owner lived in the capital or its environs.

NOTES

This copy of Le Danseur aux castagnettes was made after the Mercier etching rather than the original painting, as is registered in its reversed direction of the composition. A great many changes were introduced by the copyist: the bagpiper was replaced by a standing guitarist, the man standing at the left raises his hand to his face as though speaking, the costume of the seated man has been modified, and a low, arcaded structure has been added in the far distance.