- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Concert champêtre

Entered August 2019; revised May 2021

New York, Florence, and London, with Fabrizio Moretti

Oil on panel

59.4 x 49 cm; originally 42.5 x 32 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Le Concert de famille

M. Baugé joyant de la basse de viole

RELATED PRINTS

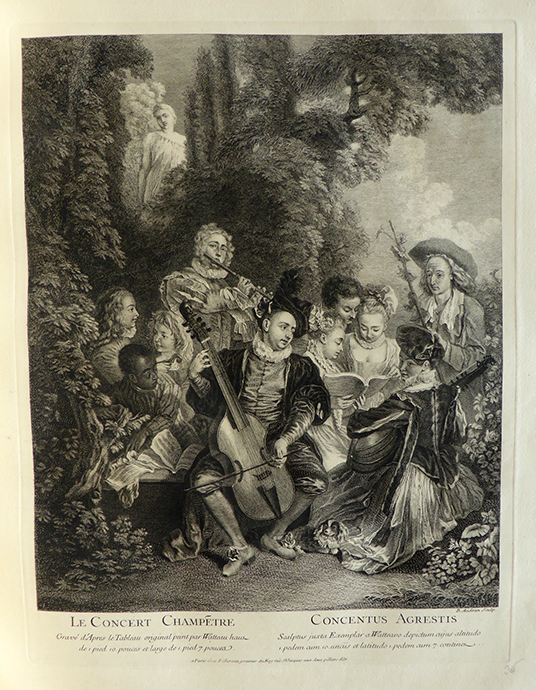

Le Concert Champêtre was engraved in reverse by Benoît Audran in 1727, and was announced for sale in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2677.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of M. Bougi. His ownership is cited on the engraving as ”du Cabinet de Mr Bougi.” For a discussion of this patron, see below.

Paris, private collection. Offered to the Musée du Louvre, on September 12, 1851

Paris, collection of Monsieur Parisez. His sale, Paris, January 25, 1868, lot 57: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . Concert champêtre. Dans un parc, des gentilshommes, des dames parées de costumes de fantaisie, se sont réunis pour faire de la musique. Un violoncelliste installé sur un banc de pierre, un joueur de flûte debout derrière lui, une dame assise à terre pinçant de la mandoline, accompagnent un jeune homme et deux gracieuses chanteuses qui lisent dans une partition qu’ils tiennent à la main. Un personnage costumé en paysan, tenant un cep de vigne, une petite fille, un petit garçon et un jeune nègre, composent l’auditoire et complètent l’ensemble de cette agréable composition. (Gravé).” Sold for 140 francs according to an annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York.

Paris, collection of Monsieur A. His sale, Paris, December 22, 1878, lot 28. It has not been possible to find this catalog.

Tours, collection of Monsieur Mame, c. 1928 (this was recorded by Réau and was repeated by Adhémar as well as Macchia and Montagni).

Collecton Champchevrier (cited by Adhémar as being formerly in this collection, i.e., pre-1950)

Paris, Sotheby’s, June 21, 2012, lot 79: “Attribué à Jean-Antoine Watteau . . . La composition du «concert champêtre» fut gravée, dans son format actuel, et en sens inverse, par Benoît Audran en 1727. Elle est également connue par une seconde estampe, anonyme, portant le titre «L'ouïe». De par sa provenance, le tableau que nous présentons est celui décrit par Camesasca dans son ouvrage publié en 1970 (voir opus cité supra). De très nombreux éléments motivent l'attribution de notre tableau à Jean-Antoine Watteau. Son sujet bien sûr, une scène musicale festive et mondaine, est caractéristique des modèles d'un genre dont l'artiste fut l'éminent représentant en France au début du XVIIème [sic] siècle. La facture également, sure et inventive, vibrante et colorée montre l'assurance d'un artiste alerte. Enfin, la technique, les craquelures profondes et larges trahissent l'utilisation d'une huile grasse fréquente chez l'artiste. Elle atteste également du métier de peintre de Watteau, revenant plusieurs fois sur une première couche encore peu sèche et instable. Cette même technique est, en autre, à l'origine des difficultés de lecture de l'œuvre (fréquentes chez Watteau) et qui nuisent en partie sa compréhension. Elle nous conduit à penser, en accord avec nombre d'historiens d'art, qu'il existe pour l'instant de très fortes présomptions que l'auteur de notre panneau soit Watteau lui-même sans pouvoir l'affirmer avec certitude. Ajoutons que cette œuvre, peinte sur un panneau, a fait l'objet très tôt dans le XVIIIème siècle d' un agrandissement sur les quatre cotés autour de la composition première . . . laissant entendre que ce pourrait bien être notre exemplaire qui fit l'objet d'une gravure dans son format actuel. . . . ” Sold for € 576, 750. (with premium) to Fabrizi Moretti.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mercure de France (December 1727), 2677.

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 192.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 69.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 70.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 55.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 119.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 67-68.

Schéfer, “Les Portraits de Watteau” (1896), 179.

Josz, “Watteau Musicien” (1902), 638-39.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 291.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 72.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat.195.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 161.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 160.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 202.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 240, 248-215.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné desdessins (1996), cat. 338, 456, 461, 463, 532, 537, 574, 577, 608, 629, R145, R835.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 220.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), 32, 66, 145, under cat. 81, 83, 97.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Less than half of the figures in Le Concert champêtre can be traced to Watteau’s drawings.

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

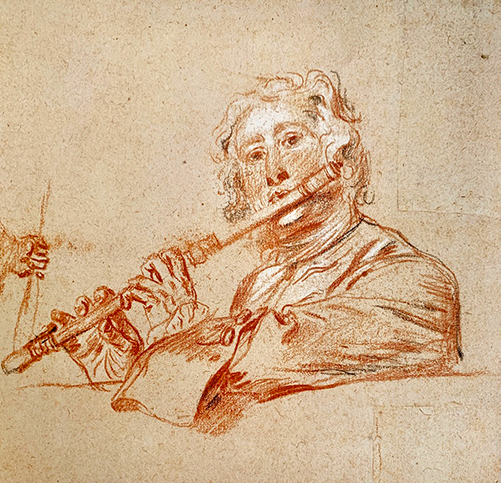

A vibrant drawing of the flutist and his elaborate costume appears on a sheet in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 532). After drawing him, Watteau used the empty space on the page for two studies of unrelated seated women. In that the flutist is without a head in the drawing, there probably was a separate study for his face. Indeed, Watteau borrowed the flutist’s head and hands from a different and unrelated sheet, a page now in the Fitzwilliam Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 577). The way in which the artist took parts of one person in one study and grafted them onto parts of a different person is truly marvelous, especially because the newly combined elements seem to have been conceived together from the start. As we can see in the Fitzwilliam drawing and in Audran’s engraving, his face suggested more personality than is found in the present state of the painting.

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

Watteau, Two Studies of a Man’s Head and Various Studies of Arms and Hands (detail), red, black, and white chalk. New York, private collection.

The head of the male member of the trio of singers in the painting was drawn on a sheet with several disparate studies (Rosenberg and Prat 456). His face is seen in several other drawings and paintings, and he thus seems unlikely to have been a member of the Bougi family.

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

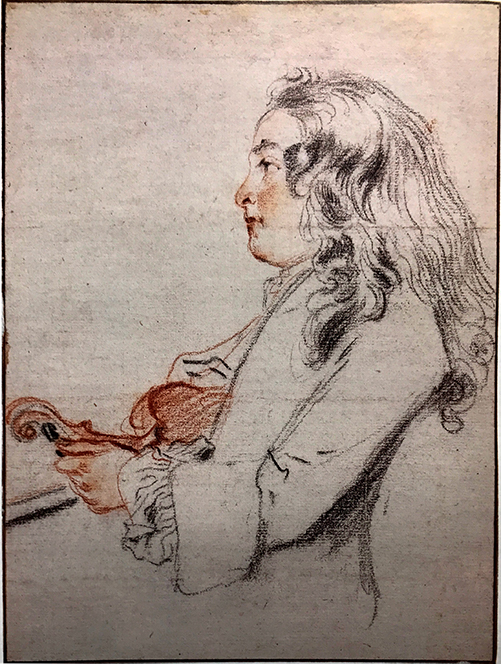

Watteau, Study of a Young Violinist, red and black chalk, 20.5 x 15.2 cm. Dublin, National Gallery of Art.

The young violinist entering the picture from the right side was based on a lovely drawing now in Dublin (Rosenberg and Prat 629). There is barely space for him in the painting, and his violin is not at all to be seen, yet it was undoubtedly his role as a musician which prompted Watteau to include him in the composition in the first place.

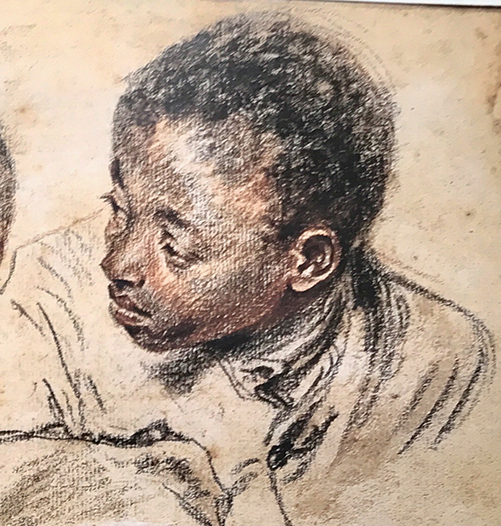

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

Watteau, Three Studies of Black Youths (detail), back, red, and white chalk. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques.

The young black servant in Le Concert champêtre was taken from a vibrant study of black men now in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 608). Although in the drawing and in the painting he has a focused expression, in truth, he seems not to be looking at anything or anyone in the painting.

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

Watteau, Two Studies of a Woman (detail), red, black, and white chalk. New York, private collection.

Watteau, Two Studies of a Woman (detail), red, black, and white chalk. London, British Museum.

Various drawings have been proposed for the two women singing. One is a study of a woman’s head viewed in profile, but in the reverse direction of the painting (Rosenberg and Prat 574). Parker and Mathey proposed this relationship, but Rosenberg and Prat rejected it.

The singer seen full face in Le Concert champêtre has been linked with a drawing in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 463). Although there are some commonalities—especially the exposed right ear—there are few other specificities. If the drawing showed the elaborate confection of bows painted on top of her head or if the chin were more compressed as in the painting, the comparison would be more convincing.

REMARKS

An important insight into the painting comes from two sources: the caption on the engraving “du Cabinet de Mr Bougi,” and Mariette’s remark in his “Notes manuscrites,” which not only reiterates Bougi’s ownership but adds “qui y est représenté jouant de la basse de viole.” Ironically, even though we have the sitter’s family name—provenance information generally hidden from us—we still are at a loss regarding the identity of the patron. In the late nineteenth century, Schefer proposed that the cellist was Guillaume Joseph de Croissy, seigneur de Bougy, conseilleur au parlement de Rouen, surrounded by his wife, five children, a black servant, a gardener, and a cousin or brother-in-law playing the flute. Alternatively, Schefer identified the cellist as Jean Jacque Révérend de Bougy, called the marquis de Cologne, a brigadier in the French army. Virgile Josz also identified a Watteau drawing of a seated Crispin (recorded in the Figures de différents caractères, plate 57) as M. Bougi. The idea that Bougi is surrounded by members of his family and staff is open to question. Not only do these figures not seem portraitistic but they look like Watteau’s regular stock of models. Most modern critics have omitted that part of Schefer’s argument but have retained Mariette’s claim that Bougi is playing the cello. There are some notable exceptions to Mariette’s statement. Posner insisted that Nicolas Vleughels was the model for the cellist. Rosenberg and Prat (under cat. 338), independently and seemingly unaware of Posner’s idea, also claimed that the cellist is Vleughels. Yet the face revealed in the x-ray and in Audran’s engraving is not Vleughels’ pudgy face.

Watteau, Sous un habit de Mezzetin, oil on panel, 27.7 x 21 cm. London, Wallace Collection.

Watteau, Fêtes venitiennes, oil on canvas, 56 x 46 cm. Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland.

How are we to understand Le Concert champêtre? The notion of combining a patron’s portrait within a scene of the commedia dell’arte has parallels in Watteau’s oeuvre, most notably with Sous un habit de Mezzetin. There Sirois and members of his family are posed in theatrical garb but this is accomplished discretely. The casual observer might be unaware that the guitarist and the older woman at his side are not regular theatrical performers. In Les Fêtes venitiennes, Watteau turned the principal dancer into a portrait of Vleughels and may have included a portrait of himself as an onlooker—all a subtle joke but one hidden from the uninitiated. Thus the portraitistic aspect of Le Concert champêtre, as unusual as it may be, was perhaps a more integral part of his oeuvre than we might have imagined.

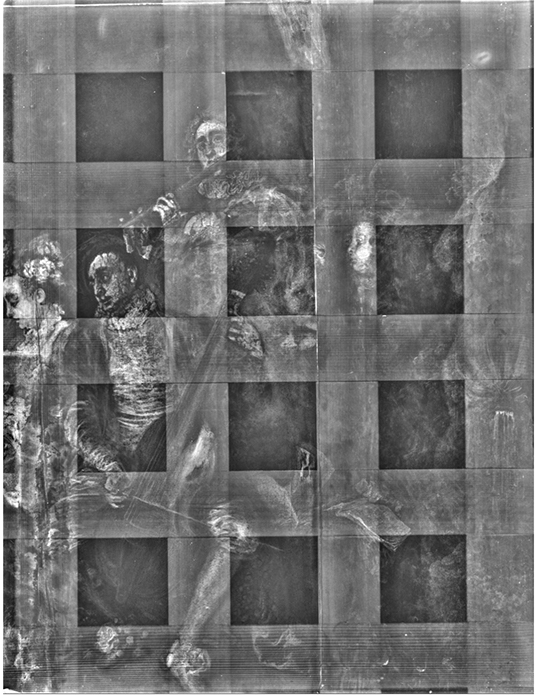

An x-ray of Le Concert champêtre taken in 2012

X-rays have revealed minor pentimenti in the composition, corresponding to the way that Watteau often resolved his compositions directly on the canvas, and thus affirm the authenticity of the painting.

Diagram showing the dimensions of the original panel set against the present state of the picture.

Conservation in 2012 revealed that the picture had originated as a much smaller panel that focused more closely on the group of musicians, extending from the gardener and woman playing the lute at the left to the flutist at the right. Watteau then extended the panel at the right to include the young violinist. Also, in the greatly enlarged space at the top, additional trees and the statue were added, as well as a greater sense of depth in the background.

X-ray of Le Concert champêtre (detail: head of the cellist).

Wattaeu, Le Concert champêtre (detail: head of the cellist).

Audran after Watteau, Le Concert champetre (detail, here reversed: head of the gardener).

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail: head of the gardener).

Like so many of Watteau’s canvases, this work has suffered from overpainting. There is considerable difference between the restored surface of the painting and the modelling evident underneath. The head of M. Bougi, the cellist, is revealed to have originally been rendered more powerfully, with more personality, unlike the bland features that are presently seen. The face of the gardener at the left is lifeless and quite unlike the one that Audran engraved.

In regard to the dating of Le Concert champêtre, there is the normal wide range of choices. Mathey, who almost always favors an early date, has suggested 1714. Adhémar, who would condense more than half of Watteau’s paintings to 1716, has proposed late 1716 for this painting. Macchia and Montagni, as well as Roland Michel, preferred c. 1717, while Rosenberg has dated some of the preliminary drawings to 1718-19. Glorieux, the latest in this sequence, has proposed 1718-1719.

The statue at the back of the painting, her drapery hanging off one shoulder à l’antique, is of interest. Some would have us believe that the statue represents the nymph Echo. If true, this would add a humorous note to this scene of music-making. The statue has a plaintive or unhappy expression on her face but, after all, Echo died a sad death from unrequited love.

Click here for copies of Le Concert Champêtre