- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Le Concert champêtre

Entered July 2018; revised October 2022

Angers, Musée des beaux-arts, inv. MBA 182 (J. 1881) P.

Oil on canvas

67 x 51 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

The Awaited Declaration

Concert dans un paysage

Concerto campestre

La Déclaration attendue

The Expected Declaration

Une Fête à la campagne

Fête de campagne

La Fête de champêtre

Landliches Konzert

Pastoral Concert

Rustic Concert

RELATED PRINTS

Le Concert champêtre was not included in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé, and was not engraved until 1904. Evidently commissioned to accompany an article by Louis de Fourcaud on Watteau’s fêtes galantes, it appeared in the November 1904 issue of La Revue de l’art. Curiously, the Angers painting was not mentioned in Fourcaud’s essay.

PROVENANCE

Paris, with Jean-Baptiste Pierre Lebrun (1748-1813; painter and art dealer). His sale, Paris,

Revérends Pères Augustins du grand Couvent, September 22ff, 1774, lot 107: “ANTOINE WATTEAU. . . . Un Tableau, sur toile de 24 pouces de haut, sur 18 de large. Il représente un groupe de six figures, dont un paysan assis qui tient un bouquet, une fille qui le regarde ayant les mains posées sur un panier, un homme joue de la flute, plusieurs arbres ornent agréablement le fond de cet tableau.” Sold for 400 livres to Pierre Remy.Paris, with Pierre Remy (active c. 1749-c.1787; art dealer).

Angers, collection of Pierre-Louis Evelliard, marquis de Livois (1736-1790); seized during the Revolution.

In 1799, transferred to the Angers government and installed first in the École centrales and then, in 1839, in the newly instituted Galerie David d'Angers.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Les Chefs-d’oeuvre (1933), cat. 114 (as Watteau, Le Concert

champêtre, lent by the Musee des beaux-arts, Angers).Paris, Palais national, Chefs d’oeuvres de l’art français (1937), cat. 228 (as Watteau, Le Concert champêtre, lent by Angers, Musée).

San Francisco, Palace of the Legion of Honor, Rococo (1949), cat. 52 (as Watteau, Le Concert champêtre [Pastoral Concert], lent by the Musée des beaux-arts, Angers).

London, Royal Academy, 18th Century (1954), cat. 262 (as by Watteau, Le Concert Champêtre, lent by the Musée d’Angers)

Brussels, De Watteau à David (1975), cat. 3 (as Watteau, Le Concert champêtre, lent by the Musée des beaux-arts, Angers).

Moscow and Leningrad, From Watteau to David (1978), cat. 20.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P 45 (as Watteau, The Expected Declaration [La déclaration attendue], lent by the Musée des beaux-arts, Angers).

Tokyo, National Museum of Western Art, Space in European Art (1987), cat. 92 (as Watteau, The Awaited Declaration, lent by the Musée des beaux-arts, Angers).

Valenciennes, Florilège (2001), cat. 3 (as Watteau, La Déclaration attendue).

Les Chefs-d’oeuvre des musées d’Angers (2002), cat. 43 (as Watteau, “La Déclaration attendue”).

Valenciennes, Musée, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), cat. 3 (as Watteau, La Déclaration

attendue [Le Concert champêtre], lent by the Musée des beaux-arts, Angers).Brussels, Leçon de chant (2013), cat. 11 and under cat. 12 (as Watteau, La Déclaration attendue, lent by the Musée des beaux-arts, Angers).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clement de Ris, Musées de province (1872), 28.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), 166.

Jouin, Musées d’Angers (1881), 53.

Jouin, Musées d’Angers (1885), 48.

Gonse, Les chefs-d’oeuvre (1900), 50.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 129.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), no. 154.

Valotaire, Musée d’Angers (1920), 13.

Nicolle, “Watteau dans les musées de province” (1921), 134-35.

Valotaire, “Le Concert champetre de Watteau” (1922), 603-08.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 43-46.

Planchenault, “La Collection Livois” (1933), 222.

Goulinat, “La Restauration des tableaux” (1936), 289, 324.

Bouchot-Saupique, "La Part des musées de province" (1937), 118-19.

Barker, Watteau (1939), 146.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 172.

Dacier, L'Art au XVIIIe siècle en France (1951), fig. 97.

Gauthier, Watteau (1959), pl. XXXVI.

Mirimonde, “Statues et emblèmes” (1962), 19-20.

Morant, La Peinture au musée d’Angers (1968), 8.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 119.

Cormack, Drawings of Watteau (1970), 22, 41.

Ferré, Watteau, (1972), 3: cat. B45.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 176.

Hochard, Musée d’Angers, Peintures (1982), 8.

Watteau, Technique picturale (1986), 35, 47.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 472, 481, 532, 577, 609, 620.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 45.

La Nouëne, Chefs-d’oeuvre (2004), cat. 48.

Angers, Musée, Chefs d’oeuvre (2004), cat. 481.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 139.

RELATED DRAWINGS

At least four of the figures in Le Concert champêtre can be related to Watteau’s drawings from the live model.

The man in the foreground, sitting on the ground and weaving a garland of flowers, can be traced to a sheet in the Petit Palais (Rosenberg and Prat 407). The artist employed the same study for L’Amoureux timide, but in that painting he gave him bright blue trousers and an equally bright red jacket.

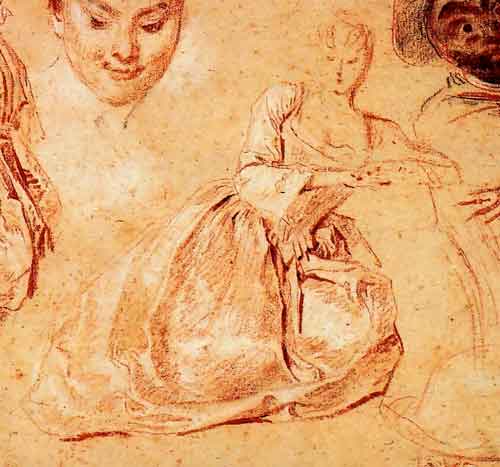

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

Watteau, A Sheet of Studies of a Seated Woman, an Actor, and a Harlequin (detail), red, black and white chalk. Paris, École national supérieur des beaux-arts.

Watteau, A Sheet of Studies of a Woman’s Bust and Hands (detail), red and white chalk, graphite, and wash. Washington, National Gallery of Art.

The woman seated on the ground, her hands resting on a straw basket, was derived from a sheet of studies now in the École des beaux-arts, Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 481). Not only did the artist borrow his full-length study of her body, but he also relied on the separate study of her head at the top of the page. It is turned at a slightly different angle, much as in the final painting. Although it is often claimed that he referred to a separate study of crossed hands that is now in Washington (Rosenberg and Prat 620), this may not have been the case. Not only are the fingers indicated in the Paris drawing but the arched position of the upper hand seen in the painting and the Paris drawing is somewhat different in the sheet in Washington.

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

Watteau, Sheet of Studies (detail), red, black, and white chalk. Paris, Musée de Petit Palais.

The woman seen from behind was taken from a Watteau drawing in the Petit Palais (Rosenberg and Prat 609). Originally the drawing must have been fuller, but the bottom of the page was severely trimmed.

The flutist at the back of the group was based upon a half-length study in the Fitzwilliam Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 577). Although he rests his arm on a parapet in the drawing, in the painting his lower body is obscured by the foreground figures and the carefully manipulated shadow. But the major aspects of the drawing—especially the position of his fingers, and even the underside of his sleeve—are closely followed. In the painting the musician wears a theatrical ruff and a large straw hat, neither of which are present in the drawing.

Reference has often been made to a Watteau study of a standing flutist now in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 532) but it has no bearing on Le Concert champêtre. Although both works depict a standing flutist, the British Museum drawing does not show the man’s head, fingers, or flute. Moreover the drawing is primarily a costume study, not of contemporary fashion as seen in Le Concert champêtre but, rather, a sixteenth-century costume with slashed sleeves.

Although Watteau made numerous drawings of children, none of his extant studies correspond to the two affectionate girls or the charming young boy in the painting.

REMARKS

Because the Angers painting was not included in the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé, we face the same sorts of problems that occur with regard to other non-engraved paintings. First, we do not know who owned the picture in the 1720s nor can we trace its whereabouts in Paris until the 1770s. Furthermore, without a Jullienne-imposed title, it probably had no fixed, formal name in its first decades. When it surfaced in the latter part of the eighteenth century, it was designated simply: “Un Tableau . . . un groupe de six figures.” Once in the Angers museum, it was christened “Fête de campagne,” and that name remained in place through the early twentieth century, being used by Valotaire and Nicolle as late as 1920 and 1921, respectively. However, in 1913 when Zimmerman’s monograph appeared, the title Concert champêtre was instituted and was used consistently by the museum and all Watteau scholars until the 1984 Watteau tricentenary.

Rosenberg objected to the traditional name because it conflicted with the title of another fête galante, one that was engraved in the Jullienne corpus as Concert champêtre. To distinguish these two works, he proposed that the Angers painting be known as La Déclaration attendue. Most publications since then have used that new title. Rosenberg claimed that it was a “straightforward interpretation of the scene.” As he explained it, the timid man in the foreground is making a bouquet of flowers for the woman but “does not dare to declare his love.” In turn, the woman “seems to await his announcement serenely.” The reading of the man’s nature as timid is undoubtedly prompted by his appearance in Watteau’s L’Amoureux timide. But is he really timid? Does he hold back from declaring his love? Such a narrative is not implicit in the painting. Even less probable is the reading of the woman's character as serenely waiting for his words of love. She seems more self-absorbed, as do most of Watteau’s characters. And what is to be made of the surrounding figures who play no part in any such amorous relation? Barker proposed a very different reading: he saw it as a simple pastoral "in which can be found no traces of exotic nostalgia and erotic desire." While it may be tempting to impose story lines on Watteau’s pictures, his is rarely a narrative art. Employing a title such as La Déclaration attendue invites a highly subjective and romantic interpretation, which is why we have continued to use the painting’s traditional name.

Watteau’s authorship of the Angers painting was recognized in the eighteenth century and continued unchallenged into the twentieth. However, a number of important critics have rejected the attribution. Perhaps the first to do so publicly was Zimmerman, who considered the execution weak and the composition only a pastiche of elements from established works such the other Concert champêtre and L’Amoureux timide. Réau did not include the painting in his catalogue. More recently, although Montagni and Macchia listed the painting among Watteau’s other works, they denied its attribution. Ferré also classified the painting (as he did many authentic ones) among doubtful works.

jpeg.jpg)

X-ray of the seated woman in Le Concert champêtre.

Watteau, Le Concert champêtre (detail).

The painting’s reliance on a number of known Watteau drawings helps sustain its attribution, as do the X-rays which show pentimenti: there are major changes in the woman’s torso and head which fully accord with Watteau’s method of working directly on the canvas. If the painting’s surface has suffered in portions, nonetheless the evidence of Watteau’s brushwork is apparent and his authorship cannot be denied.

More than a century ago Gonse suggested that the Angers painting was executed c. 1710, and when it was exhibited in Copenhagen a date of c. 1710-12 was given. Also Barker accepted a date of about 1710 but more recent scholars do not believe that this painting is so early a work. Rather, it is rightly recognized to be a work from his maturity. Adhémar proposed a date of 1716 (the year to which she consigned a too-sizable portion of the artist’s oeuvre), and this was accepted by Cormack, Roland-Michel, and most recently by Faroult and La Nouëne. Temperini proposed "1715(?)." In 1984 Rosenberg also accepted a 1716 date, but in 1996 he and Prat dated several of the preparatory drawings later (the bust of the flutist as c. 1717, and the woman seen from behind as c. 1717-18); accordingly, one would have to date the painting to c. 1717-18. Only Huyghe has dated the painting as late as 1720.

For copies of Le Concert champêtre CLICK HERE