- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

La Conversation

Entered August 2019; revised January 2020

Toledo, Ohio, Toledo Museum of Art, gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, inv.1971.152

Oil on canvas

48 x 60 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

A Conversation in a Park

Gathering of Ladies and Gentlemen in the Open

Unterhaltung im Park

RELATED PRINTS

Jean Michel Liotard after Watteau, La Conversation, 1733, engraving.

La Conversation was engraved by Jean Michel Liotard, and was announced for sale in the October 1733 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2229.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). Jullienne’s ownership is attested to on the engraving: “du Cabinet de M. de Jullienne.” It was no longer in his collection by the time an inventory was created in 1756; that manuscript is now in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

London, Collection of Thomas Baring, 2nd Baronet (1772-1848; banker). The painting was in his possession by 1837 when he lent it to an exhibition at the British Institution.

Paris, collection of Edouard Kahn (1848-1885; merchant). His sale, Paris, June 8, 1895, cat. 10: "WATTEAU (JEAN-ANTOINE) . . . La Conversation." Dans un parc, une jeune femme vêtue de rose cause avec un jeune cavalier qui paraît être Watteau. A droite un gentilhomme, probablement M. de Julienne, converse avec une dame pendant que deux autres couples devisent entre eux.

Sur la gauche, un domestique passe des refraichements à un negre qui les place sur un plateau et s’apprête à les offrir à la compagnie.

Dans le Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, dessiné et gravé d’Antoine Watteau, par Edmond de Goncourt, voici la description qui est faite de cette composition . . . Toile. H. 0m50; L.0m60.” Sold for 10,000 francs.Paris, collection of Charles Sedelmeyer (1837-1925; Austrian-born art dealer established in Paris). The painting was published in Galerie Sedelmeyer, Third Series of 100 Paintings by Old Masters (1896), cat. 8: "WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . «La Conversation» In a park, shaded by tall trees, a lady and a gentleman (the artist himself) stand in the centre of the composition. On the left an elderly gentleman (said to be M. de Julienne, the artist’s friend and patron) is conversing with a young lady, seated by his side, while, nearer the foreground, another lady in a yellow dress and black scarf, seen from behind, is speaking to a lady seated in front of her; two gentlemen are behind this group. On the right, two servants, one of them a negro, prepare refreshments. A small dog stands beside the lady in the centre. Canvas, 19 ¼ in. by 23 ¾ in. From the Collection of M. de Julienne, 1767. Described in E. de Goncourt’s «L’Oeuvre de Watteau», p. 115. Engraved by Liotard.”

Alfred Charles Freiherr de Rothschild (1842-1918; banker). His ownership was cited at the time by Nicolle (1910).

Paris, with Mme. Henri Heugel (née Rose Creed). Her ownership was cited by Gillet (1921) and by Réau (1928).

Paris, with Jacques Heugel (1890-1979).

Paris, with Heim Gallery; sold to the Toledo Museum of Art in 1971.

EXHIBITIONS

London, British Institution, Catalogue of Pictures (1837), cat. 160 (Watteau, Conversation, lent by Sir Thomas Baring, Bart.).

London, British Institution, Catalogue of Pictures (1844), cat. 121 (Watteau, Conversation, lent by Sir Thomas Baring, Bart.).

Paris, Galerie Sedelmeyer, Third Series of 100 Paintings by Old Masters (1896), cat. 83 (Watteau, La Conversation).

Paris, Petit Palais, Le Paysage français de Poussin à Corot (1925), cat. 352.

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Exposition rétrospective d'art français (1926), cat. 116 (as Watteau, La Conversation, lent by Mme. Henri Heugel, Paris).

London, Royal Academy, European Masters of the Eighteenth Century (1954-55), cat. 244 (as Watteau, A Conversation in a Park, lent by Jacques Heugel, Paris).

Zurich, Kunsthaus, Schönheit des 18. Jahrhunderts (1955), cat. 350 (as Watteau, Unterhaltung im Park, lent by the Heugel Collection, Paris).

Paris, Gazette des beaux-arts, De Watteau à Prud’hon (1956), cat. 92 (as Watteau, La Conversation).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau, 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P23 (as Watteau, The Conversation [La Conversation], lent by the Toledo Museum of Art).

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Watteau 1684-1721 (1985), cat. 37, 34, 35 (as Watteau, Die Unterhaltung, lent by the Toledo Museum of Art).

Hanover, Hood Museum, Intimate Encounters (1997), cat. 2; x, 5, 92, 101 (as Watteau, The Conversation, lent by the Toledo Museum of Art).

Paris, Jacquemart-André, Watteau à Fragonard (2014), cat. 5.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain (1854-57), 4: 97.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 123.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 68.

Gower, The Northbrook Gallery (1885), 25.

Schéfer, “Les Portraits de Watteau” (1896), 181-82.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 316.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures théatrales” (1904), 351-52.

Nicolle, “L’Exposition nationale“ (1910), 58.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), xxv, pl. 23.

Gillet, Un Grand maître (1921), 79-80.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 2: 37, 51, 63, 97, 122, 130, 161; 3: cat. 151.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1924), 37-38.

Dacier, La Gravure de genre (1925), 60.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), 14, 48, cat. 192.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 28.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), 39, 40, 85, 119, 140, 183, cat. 110.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 40-41, 67, no. 97.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 173-205.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 105.

Hitchcock in "College Museum Notes" (1971/1972), 201.

Davidson, "Museum Accessions" (1972), 239.

“News Notes” (1972), 7.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 1: 1895-97; 3: cat. B. 53.

"La Chronique des Arts" (1973), 129.

Davidson, "Museum Accessions" (1973), 440.

Boerlin-Brodbeck, Watteau und das Theater (1973), 204, 208-209, 220, 274, 330, 332.

"Treasures for Toledo" (1976), n.p.

Toledo, European Paintings (1976), 166-167.

Toledo, Guide to the Collections (1976), 65.

Morse, Old Master Paintings (1979), 298.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 148.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 111, 145-148, 150, 239.

Posner, "Les Fêtes galantes d'Antoine Watteau“ (1984), 17, 20.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 215, 266.

Posner, "Watteau, 'Parklandscapist'" (1987), 113.

Vidal, “Conversations as Literary and Painted Form” (1987), 173-77.

Whittingham, "Watteau and 'Watteau's'” (1987), 269.

Lavergne-Durey, “Les Titon” (1989), 84, 95.

Vidal, Watteau’s Painted Conversations (1992), 21-24, 32, 43, 46, 62, 134.

Wintermute, Watteau and His World (1999), 27-28.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 56, 184, 187, 321, 415, 298, G49, G 110.

Temperini, Watteau, (2002), 43, cat. 25.

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard (2008).

Sund, “Middleman” (2009), 67.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 152, 155.

Bindman and Gates, The Image of the Black in Western Art (2011), 3: 98.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), under cat. 23, under cat. 164

“La Conversation,” website of the Toledo Museum of Art, accessed August 15, 2019, http://emuseum.toledomuseum.org/objects/55384

RELATED DRAWINGS

A number of drawings are associated with La Conversation, and several shed new light on Watteau’s studio practice.

One of the drawings that Watteau used for this painting, a red chalk study, is now in the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris (Rosenberg and Prat 184). In this instance, the artist used both studies for the one painting—a practice that has already been noted in relation to his early military subjects where he took two or more studies from a single sheet. The standing figure was used for the man at the center of La Conversation and though the painted man is often identified as Watteau, in the drawing there is no sense of an attempt at self-portraiture. The seated man was used for the similarly posed one at the left of the painting. This personage is often identified as Antoine de la Roque but he bears little resemblance to the portrait that Watteau painted of him.

The man and woman standing at the far left side of the painting were taken from a single drawing now in the National Gallery of Ireland (Rosenberg and Prat 187). Here again, Watteau worked economically, taking two unrelated studies from one page and joining them magically into a united couple on the canvas.

In regard to the women seated at the side of the painting, the actual Watteau study has not survived for the lady seated to the left, shown in a three-quarter turn, holding a fan in her lap. But an etching after the lost drawing by François Boucher records this drawing as plate 130 of the Figures de différents caractères.

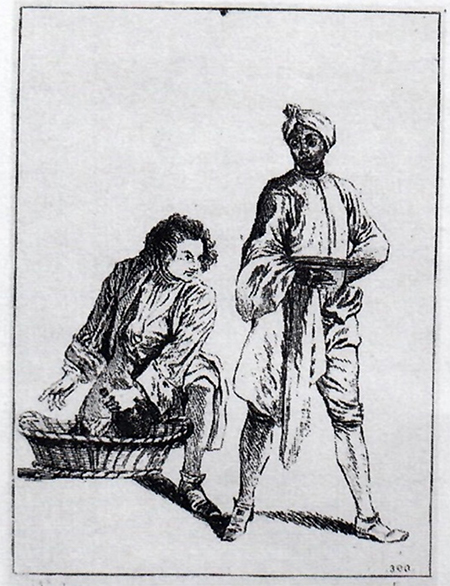

Watteau relied on at least two unrelated drawings for the standing black servant. The overall pose of the man was taken from a sheet of studies in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 321). Some of the elements of his costume, such as the cloth hanging from his waist, and the manner in which he holds his tray and cocks his head, approximate the specifics of the figure in the painting. But the London drawing is of a white man, not a black one. Indeed, the head of this black servant was taken from a different sheet which is now in the Louvre (Rosenberg and Prat 415).

François Boucher after Watteau, Two Servants, engraving, Figures de différents caractères, plate 300.

Perhaps the most problematic study related to La Conversation is the one recorded by François Boucher as plate 300 in the Figures de différents caractères. It shows the two people at the right side of the painting, the standing valet (who has already been discussed) and a kneeling servant who is handling the flagons of wine. Rosenberg and Prat question whether Boucher worked directly from the painting. This is an explanation that these authors offered about several other engravings in the Figures de différents caractères showing paired people related to paintings. However, as Eidelberg noted in his 1965 study and in the entries here for L’Avanturière and L’Alte, these pairs in the Figures de différents caractères were made after oil counterproofs that Watteau pulled immediately after he sketched the figures on the blank canvas, before any color was applied. These engravings constitute a special aspect of this suite of prints.

REMARKS

Unlike so many of Watteau’s other fêtes galantes which exude an air of intimacy and romance, this painting presents a more quotidian sense of refined society in the park of a country villa. There is no music-making or dancing, and no commedia dell’arte characters intrude. It is a more veristic portrayal of the French haut monde in the early Regency. Edmond de Goncourt expressed the same ideas more than a century and a half ago:

La composition de LA CONVERSATION, avec son absence de convention poétique, ses costumes du temps, son accent de réalité contemporaine, est incontestablement une représentation de la société de M. de Julienne.

De Goncourt identified Jullienne as the bewigged, seated man and then extended his idea by claiming that the man standing at the center of the composition was Watteau. He based the identification of the two men on a drawing that had recently appeared on the Paris market (now in the École nationale supérieur des beaux-arts, Rosenberg and Prat 184) Yet, although this drawing was indeed used for La Conversation, it should be remembered that it did not prove the identity of the two models.

From de Goncourt’s idea of viewing this picture as portrait, a series of related theses developed. Mollet followed de Goncourt and accepted the idea that the painting showed Jullienne and his family, but then his argument took a curious turn: he claimed that the perruque worn by the seated man represented “l’ancienne mode” and that this older man was Antoine Pater, disregarding the lack of resemblance to the portrait of this sculptor in the Valenciennes museum. Gillet, believing that the painting had been executed early in the artist’s career, close to 1712 when Watteau did not yet know Jullienne but did know Antoine Crozat, preferred to see this as a scene depicting Crozat and his circle. When the painting was exhibited in 1925 the standing man was still identified as Watteau, and the others were described as belonging to Crozat’s circle. In the same way Réau and then Dacier and Vuaflart accepted the idea that the standing man was Watteau, but they also contended that the seated man was Antoine de la Roque, inclined because he was leaning on his cane. Mathey fused all these ideas, accepting that this gathering represented Jullienne’s circle, with Watteau and La Roque present. This game of shifting identities has continued to the present.

Ultimately, the identification of these figures as specific people in Watteau’s circle has little merit and should be abandoned. First, these are only unreasoned, contradictory identifications resting on de Goncourt’s unfounded idea that the painting represented Jullienne’s circle. Where one critic sees Jullienne, another sees Crozat, and vice versa. Secondly, there has been no serious attempt to compare the visages in La Conversation with established portraits of the proposed sitters. Julienne was portrayed by Watteau in his Assis au pres de toy, and also by François de Troy in the canvas now in the Valenciennes museum. Antoine de la Roque was painted by Watteau (with Lancret’s participation) in a work now in Japan. Pierre Crozat’s appearance was captured by Rosalba Carriera and others. Yet there is little that links these established portraits and the characters in La Conversation. The drawings from models that served for the painted figures reinforce this, since they seem to be just models. They do not appear to be portrait studies. Although the identification of the characters with specific people may continue to be debated, the key point is that La Conversation avoids the poetic, artificial aspects of most of Watteau’s fêtes galantes. The painting mirrors actual society walking and conversing in a garden in the early eighteenth century, even if we cannot put names to the people assembled.

The provenance of La Conversation is uncharted from the middle of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. The Toledo Museum occasionally lists Pierre Crozat as an owner, but this error probably stems from some critics’ belief that the bewigged man at the left is Crozat. Lavergne-Durey proposed in 1989 that Evrard Titon du Tillet (1676-1762; author and amateur of the arts) owned La Conversation because the inventory of his collection listed “une conversation” by Watteau, but the term “conversation” was used there only in a generic way, signifying a fête galante but not the title of a specific work.

The dating of La Conversation is less problematic than for most of the artist’s paintings, with most scholars agreeing on an early date, c. 1714-15. Gillet proposed 1712. Mathey, whose chronology is generally set earlier than most, proposed not before 1712-13. The Toledo museum has often used the date 1712-15. Rand and Temperini favored 1712-14. In 1981 Roland Michel proposed 1712-14, but in 1981 she opted for 1715. Adhémar, who has squeezed half of Watteau’s oeuvre into 1716, placed La Conversation in the spring of 1716. Vogtherr and Wintermute opted for 1714, while Posner as well as Macchia and Montagni leaned to 1715. Whereas Rosenberg and Prat would date the drawing of the two seated men to 1712-13, they think that the study of the black man’s head is later, mandating a date of 1715 for the painting. In short, although there is no commonly accepted year, there is agreement within a remarkably small span of years.