- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Diane au bain

Entered June 2020

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. R. F. 1977-447

Oil on canvas

80 x 101 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Diana at Her Bath

Diana im Bade

Diane sortant du bain

RELATED PRINTS

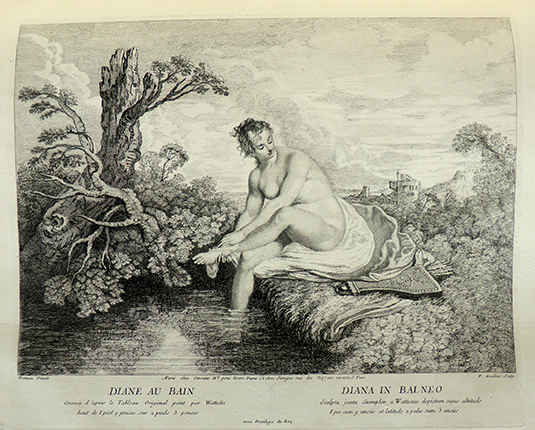

Pierre Aveline after Watteau, Diane au bain, c. 1729, engraving.

Watteau’s Diane au bain was engraved in reverse by Pierre Aveline and was announced for sale in the April 1729 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 751. Gersaint’s advertisement described it as “Diane, sortant du bain, gravée par Pierre Aveline; c’est une femme seule qui se lave les pieds à une fontaine, le sujet en est fort piquant & la manière vague dont il est traité donne parfaitment l’idée de l’original & rend une belle lumière.” Curiously, the engraving gives the painting‘s measurements as 1 pied, 9 pouces by 2 pieds, 3 pouces, i.e., 56.7 x 72.9 cm, which is considerably smaller than the actual canvas. The difference is unexplained.

PROVENANCE

Paris, c. 1729. There was no indication of ownership when the painting was engraved. Its absence from Parisian records and its subsequent presence in London sales suggests that it was taken across the Channel in the 1730s.

London, sale, May 17, 1737, collections of Sir Thomas Saunders Sebright, 4th Bart., and Thomas Sclater Bacon, lot 74 : “Vatteau, A Woman Bathing.”

Collection of Sackville Tufton, 9th Earl of Thanet (1769-1825). His sale, London, May 30, 1797, cat. 47: “Watteau . . . a nymph bathing.” The picture was withdrawn prior to the sale.

London, sale, Phillips, June 13, 1806, collection of Willmot and a person of rank, lot 16: “WATTEAU . . . Venus Bathing.” The painting sold for £2.6.0. The Watteau belonged to the person of rank; the Getty Research Center hypothesizes that these paintings may have come from the collection of a Col. Crewe.

Ipswich and London, collection of Thomas Green. His and others’ sale, Christie’s, March 20, 1874, lot 96: “A. WATTEAU. . . . A NYMPH BATHING AT A FOUNTAIN, in elaborately carved Venetian frame.” The annotated copy of the sale catalogue at the National Fine Arts Library, Victoria & Albert Museum, lists the buyer as “Mat… [illegible]” but the buyer was actually Stéphane Bourgeois.

Cologne, with Stéphane Bourgeois (art dealer). He offered the painting to the Louvre in 1894 but they could not buy it due to a lack of funds.

Paris, sale, G. Duchesne and Henri Haro, May 11, 1896: “Tableau important peint par Antoine WATTEAU « La Diane au bain» gravé par P. Aveline.” The picture sold to Christine Nillson. The sale consisted of just this painting.

Paris(?), collection of Christine Nillson, Countess of Casa Miranda (1843-1921; operatic soprano); she sold the picture to Camille Groult.

Paris, collection of Camille Groult (1837-1908; heir to a flour milling fortune); by descent to his son Jean Groult, and then to Pierre Bordeaux-Groult (1916-2007); sold in 1977 to the Louvre for 3,000.000 francs.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Gazette des beaux-arts, De Watteau à Prud’hon (1956), cat. 97 (as by Watteau, Diane au bain).

Paris, Grand Palais, Cinq années d’enrichissement (1981), cat. 39 (as by Watteau, Diane au bain).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. 28 (as by Watteau, Diana at Her Bath (Diane au bain), lent by the Musée du Louvre).

Bailey, The Loves of the Gods (1992), cat. 13 (as by Watteau, Diana at Her Bath, lent by the Musée du Louvre).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariette, “Notes manuscrites,” 9: fol. 194.

Hedouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 129.

Hedouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 131.

Goncourt, L’Art du XVIIIe siècle (1860), 56.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 36.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 61.

Dargenty, Watteau (1891), 67.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 178-79, 184.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 62.

Larroumet, Études (1893-96), 3: 72-73.

Dilke, French Painters (1899), 86.

Fourcaud, “L’existence de Watteau” (1901), 258.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 29.

Josz, Watteau (1904), 177.

Guiffrey and Marcel, Inventaire (1907), 2: under 1451.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), pl. 134.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 29-30; 2: 29, 93, 133, 159, 161; 3: cat. 149.

Seailles, Watteau (1927), 70-71.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 8.

Eisenstadt. Watteaus Fêtes galantes (1930), 69, no. 145, 183-84.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 137.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Gauffin, “Watteau på Nationalmuseum“ (1953), 10-11.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Lossky, Peintures du XVIIIe siècle (1962), under no. 17.

Mirimonde, “Statues et emblèmes” (1962), 16 and n. 17.

Nemilova, Watteau and His Works (1964), 90.

Eidelberg, Watteau’s Drawings (1965), 20-22, 51, 66.

Cailleux, “Newly Identified Drawings” (1967), 59.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 113.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), 1: 214; 3: 785, 1040, 1107.Nemilova, Enigmas (1973), 57.

Posner, A Lady at Her Toilet (1973), 31. 33.

Toledo, Chicago, Ottawa, Age of Louis XV (1975-76), under cat. 11.

Mirimonde, L'Iconographie musicale sous les rois Bourbons (1977), 84, n. 16.

Hagstrum, Sex and Sensibility (1980), 288, n. 18.

Nordenfalk, “Stockholm Watteaus” (1979).

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 207.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 151, 169.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 107.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), under cat. 261.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 42.

Eveno et al., “Palette de Watteau” (2009-10), 40-41, 46-47.

Raymond, “Watteau, Lancret, Pater” (2009-10), 194.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 174-77.

Eidelberg, Rêveries italiennes (2015), 87.

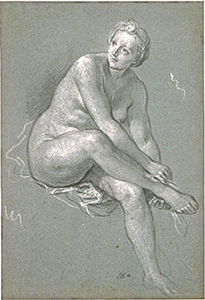

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau, Diana Bathing, red chalk, 17.2 x16.3 cm. Vienna, Graphische Sammlung, Albertina.

The beautiful compositional study of Diana Bathing in the Albertina (Rosenberg and Prat 261) naturally invites comparison with Watteau’s painting in the Louvre. It is highly finished, including the dense foliage at the right and the horizontal indications in the sky, areas that must have originally extended out still farther before the sheet was trimmed. It is as though Watteau conceived the drawing as an end in itself, in the manner of his drawing of St. Anthony (Rosenberg and Prat 361).

The inspiration for Watteau’s painting was Louis de Boullogne’s Repos de Diane, a large canvas that had been displayed in the 1702 Salon. By the time that Watteau began his Diane au bain, the Repos de Diane was hanging in the château of Rambouillet, and thus would not have been available to him. Instead, as it is generally agreed, he must have copied one of Boullogne’s preliminary studies, most probably the one which served for the nymph at the right side of the composition. Watteau took over the essential elements of the pose: the turned head, the torso bent forward and slightly to the side, her right arm and leg crossing over the left leg. Whereas this figure served for one of Boullogne's nymphs, Watteau transformed her into the goddess herself. Boullogne’s drawing bears no indication that the figure was for one of Diana’s nymphs, but Watteau must have been instructed on this point. In his drawing he hung a quiver of arrows over her head to indicate her identity.

Rosenberg and Prat have offered an alternative explanation of what transpired, what they call a “fragile hypothesis.” They would have us believe that Boullogne made a now-lost painting in which he re-used the figure of this nymph, centering his painting around her, and he added a quiver and landscape. The supposition of such a painted model seems quite unnecessary. Watteau was more than sufficiently gifted to have transformed Boullogne’s figure on his own.

REMARKS

The idea that Watteau created a picture with the principal figure borrowed from another master might seem odd, but this is the case elsewhere in his oeuvre. His Amour desarmé is based on a drawing then thought to be by Veronese, and his allegory of Autumn from the Crozat Seasons is largely based on a Rubens painting. Paying homage to the great masters of the past was an integral part of Watteau’s aesthetic program.

There is general agreement that Diane au bain is a mature work, but not from his very last years. The dates proposed show the normal spread of time. Previously I wrongly attributed it to c. 1712; Mathey assigned a date of 1713. Given Watteau’s use here of landscape motifs from Domenico Campagnola, it seems likely that the painting was executed no earlier than 1715, after Crozat’s and Vleughels’ returns from Italy, when both Watteau and Vleughels found shelter under Crozat’s roof and studied his rich collection of Venetian landscape drawings. Rosenberg and Bailey have suggested that the picture was executed in 1715-16; Adhémar put it at 1716; Macchia & Montagni proposed 1715, then 1716-17; Glorieux placed it at 1715; Roland Michel placed it still later, c. 1717-18, but elsewhere she claimed 1716. Grasselli first dated the Vienna drawing to 1716 but then shifted its date later to 1718-19, implying an equally late date for the painting.

The whereabouts of the painting in the early eighteenth century are obscure but it apparently left for England soon after it was engraved in Paris in c. 1729. It appeared in a London auction in 1739 and then disappeared from sight until the last years of the eighteenth century. It reappeared in the first decade of the nineteenth century. then fell from sight again, re-emerging only in the latter part of that century. Given these long absences, critics have sought to fill some of the gaps, using references to paintings of bathers that appeared under Watteau’s name in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sale catalogues.

Edmond de Goncourt, for example, cited a paintings sold in 1777 from the collection of the prince de Conti: “Une femme assise, & sortant du bain; du paysage, des fabriques, & un jet d’eau servent de fond. . . . “ But as even Goncourt recognized, no such water spout is present in Watteau’s Diane au bain and, moreover, the Conti painting had a vertical format. Nonetheless, reference to the Conti painting persisted in relation to the one in the Louvre—in Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold’s entry, as well as in Adhémar’s and Macchia and Montagni’s. Worse still, in all probability the prince de Conti’s painting was executed by Pater, like so many of the scenes of women bathers wrongly attributed to Watteau in the eighteenth century.

Anonymous, Le Bain rustique, oil on canvas, 46 x 56 cm. Brussels, Arenberg collection.

Goncourt also cited a picture of a bathing woman sold in Paris on January 15ff, 1783 (the catalogue is wrongly dated 1782), lot 54. He wrongly believed this to be the painting formerly in the Prince de Conti sale. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold as well as Réau and Adhémar included references to the 1783 sale in their provenance for Diane au bain. However, the text in the 1783 sale shows quite clearly that a different picture was being offered: “Antoine Watteau . . . Une femme sortant du bain occupée à s’essuyer les pieds; elle est vue par le dos; près d’elle sont des vêtements & autres accessoires.” Since she is posed with her back to the viewer, this unequivocally excludes this painting from any association with Watteau’s Diane au bain. Quite likely the picture in question was by Pater, such as one recorded in the Arenberg collection. A prominent element in this composition is the woman climbing out of the stream, her back turned to us. This motif is one that Pater particularly favored, and he employed it in countless paintings.

Louis Desplaces after Carlo Maratta, Diana at Her Bath, engraving.

In contrast to the customary depictions of Diana and her nymphs, which are generally busy scenes (despite Diana supposedly being at rest), Watteau’s isolated goddess is a contemplative, inward-looking figure. Although Watteau’s nude has been compared with Rembrandt’s late, moody Bathsheba, a more appropriate comparison might be with Italian paintings such as Carlo Maratta’s Diana at Her Bath. Perhaps it is just fortuitous, but the curled posture of Maratta’s nude and the overall mood of his picture are quite like Watteau’s.

Also, the traditions of Venetian art were not far from Watteau’s mind when he painted this work. Indeed, the picturesque buildings and mountains in the background reflect Watteau’s reliance on landscape drawings by Titian and Campagnola. Bailey described the buildings as “modest dwellings of indeterminate character and hardly appropriate for Diana’s domain.” Yet they have a distinct character and are highly appropriate for the goddess’ domain. The asymmetric structure with its wide gables and high tower represents a type of architecture frequently found in the Venetian landscape drawings in Pierre Crozat’s collection, drawings that Watteau saw and copied (for example, Rosenberg and Prat 342). Then attributed to Titian but now mostly given to Domenico Campagnola, these drawings not only represented a golden age of art but also allowed Watteau glimpses of Italy, a land he had longed to visit. Some of the backgrounds in Watteau’s fêtes galantes are virtual replicas of Campagnola’s designs. The analogies between the architecture in Diane au bain and that found in Campagnola’s drawings demonstrates Watteau’s purposeful intent.

The technical aspects of Watteau’s painting technique recently underwent careful scrutiny in the Louvre’s laboratories, and the Diane au bain was among the pictures that were analyzed. But one of the picture's unexplained aspects is its chalky appearance. It looks almost as if it had been painted on plaster, like a fresco. I do not recall encountering this quality in other paintings by Watteau.

Click here for copies of Diane au bain.