- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Leçon d’amour

Entered July 2025

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv. NM 5015

Oil on walnut panel

44 × 61 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Kärlekslektionen

Konserteren

Der Liebesunterricht

Die Liebeslehre

Die Liebeslektion

Love Lesson

RELATED PRINTS

Philippe Mercier after Watteau, Leçon d’amour, engraving, c. 1722-24, Vienna, Albertina Museum.

Exceptionally, Watteau’s composition known as Leçon d’amour was engraved twice, both times in reverse of the original canvas. While they agree in the principal elements of the composition, the two prints differ considerably in their depiction of the trees’ foliage.

It is generally thought that the print by Philippe Mercier was executed first, and that it was done on its own rather than as part of a series. It is not signed in full but, initialed “P.M del. et sculpt.” Hédouin wrongly thought that the initiais « PM»referred to Pierre Mariette, an idea repeated by Charles Leblanc, but rejected by all subsequent scholars. Dacier and Vuaflart set matters right, identifying the engraver as Philippe Mercier. The engraved legend bears an elaborate dedication to the Comte de Caylus, who visited London c. 1721-24, and a retouched proof in the Albertina is inscribed “Sold by B. Baron in Panton Square Pickadilly.” For these reasons, Dacier and Vuaflart reasonably proposed that Mercier’s etching was executed in London in conjunction with Caylus’ visit to the English capital.

Charles Dupuis after Watteau, Leçon d’amour, engraving, 1734.

The second engraving after Leçon d’amour is the one commissioned by Jean de Jullienne for the Oeuvre gravé. It was executed in reverse of the painting by Charles Dupuis. The caption on the print bears not only Dupuis’ name but also the date 1734. Indeed, the print was announced for sale in the October 1734 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2265-2266), at which time the picture was designated as in the “Cabinet de Mr de Jullienne.” The measurements were given in the opposite order of the actual dimensions of the painting. The painting was wrongly described as “haut de 2 pieds sur 1 pied 6 pouces de large” (app. 64.8 × 48.6 cm), whereas, in reality, the width is greater than the height.

PROVENANCE

London, unidentified private collection. It was engraved there by Philippe Mercier, and dedicated to the comte de Caylus, who was in England c. 1721-24.

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory), by October 1734, according to the print executed by Charles Dupuis. The painting is not listed or illustrated in the manuscript catalogue of Jullienne’s collection, which was prepared before 1756 and is now in the Morgan Library & Museum. It is also absent from the inventory of the Jullienne estate prepared between Ma and August 5, 1766, and now in the Archives nationales, Paris.

Potsdam, collection of Frederick II [Frederick the Great] (1712-1786; king of Prussia). It then was transferred to Potsdam, Schloss Charlottenburg, by 1768; Berlin, Schloss, by 1853; and subsequently Potsdam, Neues Palais, 1889-1926.

As part of the peace settlement after World War I, the picture was given in compensation to the Hohenzollern family in 1926.

Berlin, with Hugo L. Moser (1882-1972; art dealer). Moser moved to New York in 1933.

New York, Paris, and London, with Duveen Brothers, by 1951.

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum. Purchased from the Duveen Brothers in 1953.

EXHIBITIONS

Berlin, Königliche Akademie, Exposition d’œuvres de l’art français (1910), cat. 74 (as by Watteau, Der Liebesunterricht, lent by ”Seiner Majestät des Kaisers und Königs“ [of Prussia]).

London, Royal Academy, French Art (1932), cat. 172 (as by Watteau, The Love Lesson, lent from a Swiss collection).

Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, French Painting (1951), cat. 76 (as by Watteau, La Leçon d’amour, lent by Duveen Brothers, Inc.).

Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, Fem Sekler Fransk Konst (1958), cat. 63 (as by Watteau, Konserteren, Le Concert, or La Leçon d’amour, lent by the Nationalmuseum).Stockholm, Nationalmuseum,1700-tal: Tanke och form i rokokon (1979), cat. 492 (as by Watteau, Kärlekslektionen, lent by the Nationalmuseum).

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), 12, 147, 152, 165, 176, 183, 220-1, 223, 372, cat. P 55 (as by Watteau, The Love Lesson [Leçon d’amour], Nationalmuseum).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mercure de France (October 1734), 2265-66.

Hédouin, "Watteau" (1845), cat. 98.

Hedouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 99.

Goncourt, L'Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Cellier, Watteau (1867), 85, 88.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 144.

Dargenty, Watteau (1891), 81, 132.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 186.

Phillips, Antoine Watteau (1895), 56, 64, 67.

Rosenberg, Watteau (1896), 56, 60.

Dilke, French Painters (1899), 81, n. 5.

Seidel, Collections d’oeuvres d’art françaises (1900), cat. 150.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 58, 136.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 320-21.

Fourcaud, “Scènes et figures théâtrales” (1904), 344.

Josz, Watteau (1904), IX, 141, 142 n. 1, 221.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), 80, 84 n. 1, 85, 104, 114, 150.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), 187, 191, no. 82.

Maurel, “A propos de «l’Enseigne de Gersaint»" (1913), 74.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 102, 164, 240; 2: 1, 39, 51, 60, 63-64, 94, 97-99, 101, 122, 130, 142, 152, 158, 162 ; 3: cat. 263.

Förster, Das Neue Palais (1923), 61.

Réau, "Watteau" (1928), cat. 128.

Parker, Drawings of Watteau (1931), 12, 36.

Wilenski, French Painting (1931), 108.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), 44, 79, cat. 138.

Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute. French Painting 1100-1900 (1951).

Nordenfalk, Watteau (1953), 153-56.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1957), cat. 427, 529, 632, 779, 804, 897.

Macchia and Montagni, L'opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 191.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A 21.

Jean-Richard, L’Oeuvre gravé de Boucher (1978), cat. 86.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 190.

Stockholm, Watteau i Nationalmuseum (1984), 46-53.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 204, 223, 230, 260.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 111, 154, 157, 160, 174, 283, n. 59, 285, n. 71.

Bergeon, "Quelques points" (1987), 136.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 433, 456, 461, 488, 507, 553, 558, 605, 609, 634, R 159, R 558.

Wintermute, Watteau and His World (1999), 23, 136.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 72, cat. 70.

Valenciennes, Musée, Watteau et la fête galante (2004), 61, 195, 202, 224.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 254, 258.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. A 3.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 238.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), 39, 117, 202.

Paris, Jacquemart-André, Watteau à Fragonard (2014), cat. 6, 80, 92, 208.

Valenciennes, Musée, Rêveries italiennes (2015), 83-7.

Plomp and Sonnabend, Watteau: Der Zeichner (2016), 218 (under cat. 65-66).

Nickel, Die Landschaftszeichnungen von Domenico Campagnola (2017), cat. 185.

Moulinier, “La tenture des douze mois” (2024), 20-25.

Chantilly, Musée Condé, Les Mondes de Watteau (2025), 96.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Most of the principal elements in Leçon d’amour (the landscape, figures, dog) were preceded by drawings—except for the woman reading the music score at the right of the composition.

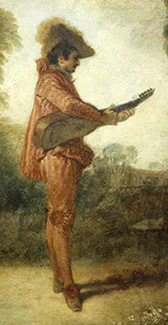

The standing guitarist in Leçon d’amour replicates the character featured in L’Enchanteur. Both musicians were undoubtedly based on a drawing that has not survived, but which was recorded in the Figures de différents caractères (Rosenberg and Prat G50 and R159). Critics such as Parker and Mathey, Jean-Richard, and Rosenberg and Prat have argued that the print might have been executed after the character in L’Enchanteur. However, there is no indication that any of Jullienne’s team of engravers for this project based their designs on figures from Watteau’s finished paintings. Rather, they seem to have remained scrupulously faithful to the program of the Figures de différents caractères, namely to record Watteau’s drawings.

Watteau, Nine Studies of Heads (detail), red, black, and white chalk. Paris, Petit Palais.

For the face of the guitarist in Leçon d’amour, Watteau turned to a sheet of studiesnow in the Petit Palais (Rosenberg and Prat 609). This would have augmented the lost, full-length study of the guitarist. This actor with a distinctive, prominent nose, has long been identified as Jean Lebouc-Santussan, an identification that has recently been proven incorrect (see Chantilly 2025, cat. 10).

The head of the woman seated close to the center of Leçon d’amour, looking up to the right, was based on a study in the upper left corner of a sheet in Haarlem (Rosenberg and Prat 634).

The woman picking flowers in Leçon d’amour was based on a drawing now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Rosenberg and Prat 488). This woman was also used in Réunion en plein air, now in Dresden.

The face of the man looking down over the shoulder of the woman reading the score on the right corner in Leçon d’amour was based on a drawing now in the Eveillard Collection (Rosenberg and Prat 456).

A sheet of studies in British Museum was used for the hand of the man on the right of Leçon d’amour. Like other Watteau drawings, it had been counter-proofed before the artist turned to it for the Stockholm painting. This argument, first formulated by Parker and Mathey, has subsequently been doubted by (Rosenberg and Prat 507).

The dog in the foreground of Leçon d’amour can be traced to a sheet of studies of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels in a private Fontainebleau collection (Rosenberg and Prat 553).

The distant, Venetian-inspired landscape of Leçon d’amour was based on a Domenico Campagnola drawing that Watteau copied. This is not a unique occurrence. In fact, copying Venetian landscapes was a standard part of Watteau’s modus operandi. In 1967, Eidelberg showed that the landscape in Watteau’s Amusements champêtres was based on a Campagnola drawing now in the Besançon Musée des beau-arts, he had seen in the collection of Pierre Crozat. In 1984, Grasselli followed suit, associating the background of Leçon d’amour with a Watteau drawing after Campagnola now in the Art Institute of Chicago (Rosenberg and Prat 433). The Campagnola sheet had also undoubtedly been in the Crozat collection when Watteau saw it. That drawing was subsequently cut on its four sides, but Watteau’s copy records what was trimmed away.

Charles Nicolas Cochin, after Watteau, Le Bosquet de Bacchus (detail, reversed

engraving.

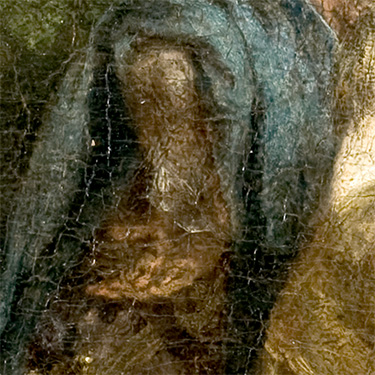

Watteau, Leçon d’amour (detail).

Watteau, Divertissements champêtres (detail). London, Wallace Collection.

Unidentified French artist, Nude Woman Sitting on Her Right Leg, brush and oil (?) on paper, 35 × 18.4 cm. Whereabouts unknown.

The statue of a nude woman that appears at the right side of Leçon d’amour is also seen in two other Watteau paintings: Le Bosquet de Bacchus and Divertissements champêtres. There also is an oil-on-paper study of the same figure in a private collection that previously was given to Watteau but more recently has been rejected (Rosenberg Prat R 558). The nature of this study is unclear. Is it a painted oil sketch or an oil counterproof, pulled by Watteau or by an assistant from one of the related pictures? Was this the intermediary that allowed Watteau to repeat this statue in his various paintings? At present there is no solution to these intriguing possibilities.

REMARKS

Watteau, Leçon d’amour.

Watteau, L’Enchanteur, oil on copper, 18.9 × 25.6 cm. Troyes, Musée des beaux-arts.

Leçon d’amour is a variation on an earlier composition known as L’Enchanteur, and now in Troyes. Actually, they are quite different pictures save for the guitarist. In the Troyes painting, the two women sit in stiffly posed postures, whereas in the Stockholm version, though still seated, they are set at slight angles, creating a richer sense of fluent movement and spatial depth. The differences between them exemplify the artist’s stylistic development.

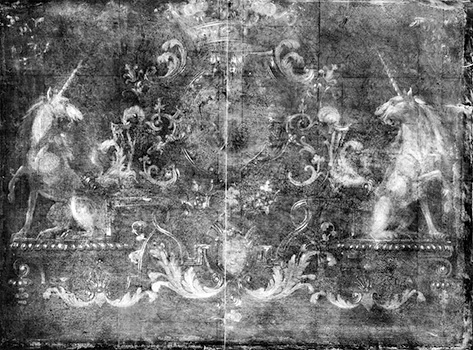

The Stockholm picture is one of several panel paintings that Watteau executed over already existing works. Another of these is the Sérénade italienne, also in the Nationalmuseum; it was painted over a decorative arabesque. The underlying picture beneath Leçon d’amour was discovered when the painting entered the collection of the Nationalmuseum and was published by the museum’s director, Carl Nordenfalk.

As shown in the reconstitution proposed by Arnold Hansen in 1953, the underlying composition is a symmetrical arrangement with a central medallion surrounded by heraldically opposed unicorns, a crown, and other decorative elements. The overall design conforms to similar arrangements by Claude III Audran, one of Paris’ leading ornamentalists and an artist with whom Watteau had direct ties. It has been proposed that the panel served as a coach door. Unfortunately, neither the particular crown nor the unicorns can be related to the coat of arms of a specific patron.

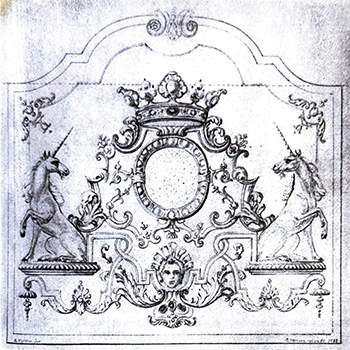

Claude III Audran, Design for a tapestry with Two Unicorns, Black and red chalk, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum.

Claude III Audran, Design for a tapestry with Two Unicorns, Black and red chalk counter-proof, pen and black ink, gray wash, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum.

Claude III Audran, Design for a Tapestry with Two Unicorns, Pen and black ink, gouache, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum.

Several drawings from Audran’s workshop show a similar disposition intended for a tapestry. Three stages in its development are preserved in the Stockholm museum.

The association of Watteau and Audran has implications for the dating of Leçon d’amour, but they are not straight forward. While Watteau worked with Audran around 1709, he was still associated with him several years later. Moreover, there is no need to believe that Watteau used the panel immediately after Audran abandoned it. With remarkable unanimity, all scholars date Watteau’s preparatory drawings between 1715 and 1718, and the painting of Leçon d’amour to the years just before or after c. 1715.

For copies of Leçon d’amour, CLICK HERE