- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

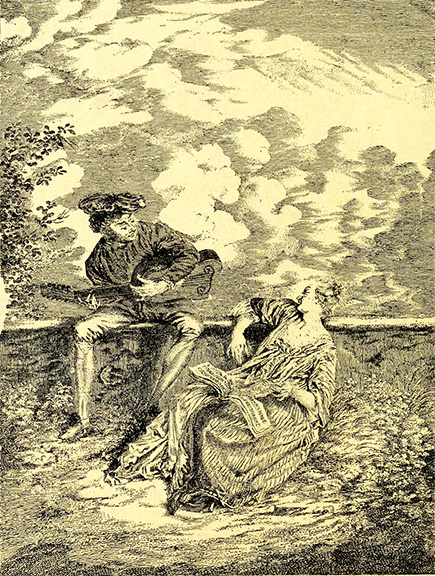

La Leçon de chant

Entered December 2024

Madrid, Palacio Real, inv. 10002404

Oil on canvas

40.5 × 32.5 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Le Duo

Un hombre tocando la guitarra

La leçon de chant

La lección de canto

La lezione di canto

Una madama con un caballero que toca una citara

Un mancebo tocando un instrumento

La Partie de musique

Le Prélude

The Singing Lesson

A Sweet Singer

Un trouvère

Un trovador

RELATED PRINTS

Watteau’s Leçon de chant was not engraved for Jean de Jullienne’s Œuvre gravé, nor was its pendant, L’Amoureux timide. That may indicate that both paintings had already been taken to Spain before work on the Oeuvre gravé had commenced. In 1922 Dacier and Vuaflart noted that there was a unique, anonymous print after this composition in the Paris collection of Jules Strauss (1862-1943). The print has no caption associating the image with Watteau, nor is the engraver identified. Adhémar identified Charles Nicolas Cochin as the engraver, but there is no reason to presume that she was correct. The print is in the opposite direction of the painting.

PROVENANCE

Madrid, collection of Florencio Kelly (d. 1732; doctor to King Felipe V of Spain, antiquarian and art dealer). This painting and its pendant, L’Amoureux timide, were cited in Kelly’s July 1732 probate inventory cat. 14: “originales de Watto, valorados en 1.667 reales.”

Madrid, by descent to Juan Kelly (1704-1763); by descent to his wife. The two pendants were cited in a list of paintings meant to be purchased from Juan Kelly’s widow for the royal collection via Antonio Rafael Mengs, cat. 88: “Dos: une con un hombre tocando la Guitarra y otra con una muger que forma un ramillete, de poco mas media de bara alto, y tercia de ancho, originales de Batto” appraised at 2,600 reales, sold on November 2, 1764.

Madrid, collection of King Carlos III of Spain (1716-1788) .

Madrid, Spanish royal collections. Placed in the Royal Palace of Madrid in 1772, Paso de tribuna y trasquartos (inventory of the Spanish Royal Collections, no I2788, 18: “Dos iguales que sinifican cada uno una muger con un mancebo tocando un instrumento de media vara encasa de caida y tercia de ancho escuela de autor Frances”). Probate inventory of Carlos III, 1789, Palacio Nuevo, Pieza de paso á la de bestir: “88 y 88 Dos de media vara de alto y tercia de ancho: el primero una madama con un Caballero que toca una Citara y el segundo otra madama y un Caballero sentado en el Suelo: los dos Escuela francesa...720 [reales]”. Moved to a passage close to the chapel of the Palacio Real de Madrid in 1808. Transferred to the Museo del Prado in 1819 or in 1824; then to the Monasterio del Escorial by 1857. Casino del Principe, del Escorial in Fall 1865 until at least 1907. Maybe, La Granja, or already moved to the Palacio Real by 1919; then to the Palacio Real, Madrid.

EXHIBITIONS

Washington, Paris, and Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), cat. P 43 (as by Watteau, The Singing Lesson [La leçon de chant], lent by the Palacio Real, Madrid ).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Poleró, Catálogo de San Lorenzo (1857), cat. 792.

Madrazo, Catálogo descriptivo é histórico del Museo del Prado(1872), xliii, note 1.

Araujo Sánchez, “El fin del arte es la expresión del alma” (1874), 570 .

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), 183.cat. number ? , under cat. 562.

Calvert, The Escorial (1907), pl. 174.

Nicolle, “Watteau dans les musées d’Espagne” (1921), 150.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), under cat. 316bis.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 115.

Saltillo, “Casas madrileñas del siglo XVIII” (1948), 17-20.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 175.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son œuvre dessiné (1957), under cat. 593.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 191.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A 20.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 223a.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 187.

Luna, “Watteau et l’Espagne” (1987), 280.

Fernández-Miranda y Lozana, Inventarios reales (1989), vol. 1, no. 91, 20.

Águeda, “Una colección de pinturas comprada por Carlos III” (1989), 289, 290-1.

Águeda, “La colección de pinturas de Juan Kelly” (1990), 493.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), under cat. 329.

Sancho, “Cuando el Palacio era el Museo Real.” (2001), 111, no. 125.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 100.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), under cat. 10, 92, 114b.

Patrimonio Nacional database, “La lección de canto”: https://www.galeriadelascoleccionesreales.es/obra-de-arte/la-leccion-de-canto/11ad0e1e-88f0-48c8-8d63-9d80987452ca\

RELATED DRAWINGS

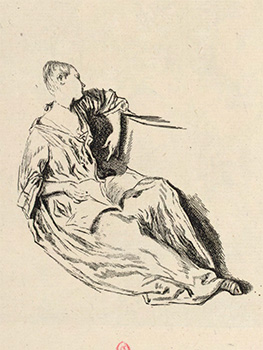

The woman in the Madrid painting is based on a trois crayons study in the British Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 329) . While the woman in the drawing is posed upright, in the painting her head and torso have been canted back to create a less static pose. Although the angle of inclination has shifted, the basic disposition of the drapery folds is unchanged.

Rosenberg and Prat contend that the woman in the painting was not based on the drawing in the British Museum but, rather, on a closely related study which has not survived. This lost drawing, they contend, is recorded in an engraving by Laurent Cars (Figures de différents caractères plate 336). However, we believe, the Cars etching is based on the sheet in the British Museum . If one compares the Cars engraving and the British Museum drawing, especially after reversing the Cars engraving to compensate for the reversal that occurs in the engraving process, it is striking to see how close the two are—line for line and darkened emphases—there should be little doubt that the two images are interdependent.

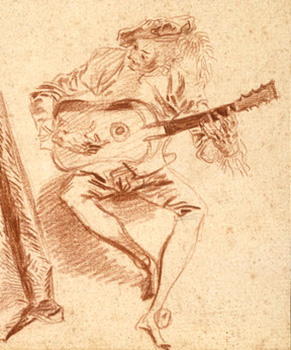

The guitarist in La Leçon de chant was based on a drawing that seems not to have survived. A drawing closely relates to the lost study is in the Ashmolean Museum (Rosenberg and Prat 267) . The lost drawing and the one in Oxford show the same costumed musician looking down to our left, his torso slight inclined. They differ in the way that the man holds his guitar and, more noticeably, in the positioning of his legs. In the lost drawing, as in La Leçon de chant, his legs are splayed whereas in the Oxford drawing they are brought together. One would imagine that the two drawings were part of a series based on the same model.

REMARKS

La Leçon de chant and its pendant, L’Amoureux timide, remained together from the time of their inception to the present.Because they were in Spain at such an early date, and because they were not engraved in the Jullienne corpus, theywere unknown to the public at large until the publication of Jean Laurent’s photographs of Madrid, its landmarks, and works of art. They became more fixed in the public’s mind after their mention in Edmond de Goncourt’s 1875 catalogue. A century ago Nicolle went to Madrid and sought out the pair of paintings but could not locate them, largely because he searched for them in the Prado and not in the Palazzo Real. Indeeed, these two paintings have reamined elusive, even into modern times. Except for their inclusion in the tricentenary exhibition of 1984-85, it would seem that few critics outside of Spain, have seen the pictures firsthand.

Adhémar was the first to suggest a date for these works: late 1716. All other critics who have tackled the issue of chronology have similarly proposed a date of execution ranging from 1716 to 1718. Rosenberg opted for the earliest date , c. 1716, Roland-Michel suggested 1717-18, while Macchia and Montagni advanced 1718. Temperini proposed c. 1718 -1719. Rosenberg and Prat suggested a date of 1715 for the drawing of the seated woman and c. 1716 for the related guitar player, thus supporting a dating of the painting after 1716.

La Leçon de chant and its pendant might seem to excerpts from larger fêtes galantes but, in fact, the figures do not appear in the painter’s more evolved compositions. If they focus on a theme of romance and courtship, it is rendered with a poetic vagary. Despite the traditional title La Leçon de musique, the man and woman do not appear to be engaged in any sort of instructional dialogue. None of the tension that normally is involved in such activity is present; here the man and woman are relaxed, even languid. The pendant, L’Amoureux timide, maintains a similar mood of quiet interaction. According to Rosenberg, the two Madrid pictures in have a common theme of “the expected declaration”—a subject he claimed for other Watteau pictures such as the one in Angers, traditionally known as Le Concert, but which Rosenberg would retitle “La Déclaration attendue.”

For copies of La Leçon de chant, CLICK HERE