- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

La Mariée de village

Entered January 2026; revised February 2026.

Charlottenburg, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten, inv. GK I 5603

Oil on canvas

65 × 92 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Der Brautzug

Die Dorfbraut

The Village Bride

RELATED PRINTS

La Mariée de Village was engraved in reverse by Charles Nicolas Cochin. The print was announced for sale in the March 1729 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 542.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean François Lériget de la Faye (1674-1731; lawyer and diplomat). La Faye’s ownership is cited on the Cochin engraving. Possibly listed (with no author name) in his probate inventory with a pendant: “Item numero cent trente un deux tableaux peints sur toilles représentants des noces de villages dans leur bordure de bois sculpté prisés cent livres.”(Paris, Archives Nationales, MC/ET/I/355.) In his will, Lériget de la Faye asks the comtesse de Verrüe to chose twelve paintings from his collection to thank her for her help and kindness (April 5, 1724, MC/ET/I/354).

Paris, collection of Jeanne-Baptiste d’Albert, comtesse de Verrüe (1760-1736), by 1735; according to the Mercure de France, October 1735, p. 2252. Possibly listed (with no artist’s name) in her probate inventory: “Item no 74 un tableau peint sur toille dans sa bordure de bois doré représentant une noce de vilage prisé douze cent livres” or “Item no 102 un tableau peint sur toile dans sa bordure de bois doré représentant une noce de vilage prisé quinze cent livres” (MC/ET/I/380). The painting is not listed in the catalogue of her sale, Paris, March 27, 1737.

Berlin, collection of Frederick II [Frederick the Great] (1712-1786; king of Prussia), by July 1750. Its restoration is documented in Frederick II’s Monatliche Schatullrechnungen (fol. 12, No. 4).

EXHIBITIONS

Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg, Meisterwerke (1962), cat. 89 (as by Watteau, Der Brautzug).

Paris, Louvre, La Peinture française, (1963), cat. 32 (as by Watteau, La Mariée de Village).

Frankfurt, Städelsche Kunstinstitut, Einschiffung nach Cythera (1982) cat . Cd 1-2 (as by Watteau, La Mariée de village, lent by Staatliche Museen, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1984-1721 (1984), (cat. P 11: as by Watteau, The Village Bride [La Mariée de Village.])

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mariettte, Notes manuscrites, 194.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 126.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 128.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 57.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 148.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), cat 148.

Dohme, Watteau (1883), 101.

Seidel, Die Kunstammlung Friedrichs des Großen (1900),cat. 149.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), pl. 12.

Maurel, “Les Collections d’art français de Guillaume II”(1919), 23.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 3: cat. 111.

Förster, “Das Gegenstück zu Watteaus ‘Brautzug’” (1924), 27-29.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 89.

Alvin-Beaumont, Le Pedigree (1932).

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 53.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1957), cat. 5, 40, 42, 51, 141.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 67.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 63.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A 4.

Banks, Watteau and the North (1975), 33-34.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 96.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 209, 213-14, 266.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 21-22, 123.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, Catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 21, 99, 104, 137, 187, R 64, R 324.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 34-35, cat. 16.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008), 148, 153, 210-11.

Paris, Louvre, Watteau et l’art de l’estampe (2010)

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 71-72.

Ziskin, Sheltering Art (2012), 52.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013)

Valenciennes, Musée, Rêveries italiennes (2015), 44-45.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau’s extant drawings offer insights into the various ways that he formed La Mariée de village. A sheet in the Louvre with five red chalk studies of a standing man (Rosenberg and Prat 99) was one of the sources for the painting. The man at the left of the drawing, seen from behind, his hat tucked under his arm, was used for a man who appears in the left foreground of the painting.

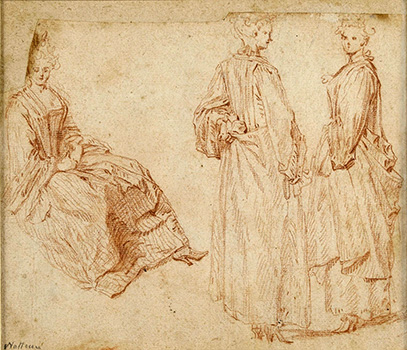

Watteau, Seven Studies of Women and Men, 23.2 x 17.4 cm, red chalk, Dijon, Musée des beaux-arts.

Also related to the genesis of La Mariée de village is a drawing in the Musée des beaux-arts of Dijon (Rosenberg and Prat 137). Its format of five characters distributed on two levels is a scheme found on a number of early Watteau drawings (Rosenberg and Prat 18 recto, 52, 62, 102, 127) and which is generally understood as following a practice borrowed from his teacher, Claude Gillot. The intriguing question is whether the figures on the sheet in Dijon were studied by the artist from a succession of live models or are compilations from other Watteau drawings. The latter is the case, as is demonstrated by the man in the top row, second from the left. He is a somewhat cursory copy from the sheet in the Louvre discussed above.

A drawing of three women in the collection of the Musée Carnavalet (Rosenberg and Prat 104) inspired the character posed in the right foreground of the Berlin painting. But whereas in the drawing she turns her face toward the viewer, in the painting her head is turned in profile. The artist also borrowed this figure for La Musette and Le Bal champêtre, and in these other instances her face is again set in profile.

A drawing in Dublin (Rosenberg and Prat 167) sheds additional light on Watteau’s method of working. In format—three independent figures, presumably studied from life, arranged in a row across a standard size —it is related to some of the drawings discussed above, especially the one now in the Carnavalet Museum. Watteau relied on the central study of the old man with a cane for the figure of the father leading the bridal procession in La Mariée de village.

An intriguing question focuses on the bridal procession at the left side of the painting and a compositional drawing of that same group now in Washington (Rosenberg and Prat 21). As noted above, his study of the father leading the bridal party can be traced to the drawing in Dublin. Can we not presume that the Washington compositional drawing was based on the painting in Berlin? It is the age-old quandary of the chicken and the egg.

Watteau, La Mariée de village (detail).

Although it is evident that these drawings are closely bound to La Mariée de la village, it is possible that the process was more complex. Some ten of the figures that appear at the right side of the picture also appear at the right side of La Musette. As discussed elsewhere, several issues arise, specially which of the two pictures was created first. The chronology of the two works is contested, and no scholarly consensus has yet emerged. Technical examination—most notably radiographic analysis—could, in principle, clarify the sequence of execution by revealing pentimenti or compositional adjustments beneath the painted surface. In any event, it is evident that Watteau used his drawings for one of the paintings, and then copied them from the first painting for his second version.

REMARKS

Watteau, L’Accordée de village, oil on canvas, 63 x 92 cm. London, Sir John Soane‘s Museum.

It has been proposed that La Mariée de village was originally paired with L’Accordée de village. Their sizes match, they are thematically linked, and they are comparable in style and date of execution. Originally the two paintings must have been together as pendants.

It has been suggested that La Mariée de village was once in the collection of Joseph Antoine d'Aguesseau de Valjouan (1676-1744; conseiller to the Paris Parliament). This idea stems from a remark by the comte de Caylus, c. 1748: “une Accordée ou Noce de village faite pour M. De Valjoin.” However, his reference is illlusive and could as well refer to other Watteau paintings with this theme.

La Mariée de village is one of several important compositions from the early portion of Watteau’s career that feature multitudes of figures. They include Camp volant and Retour de campagne, Départ de garnison, La Signature du contrat, Les comédiens sur le champ de foire, and L‘Accordée de village—works that take delight in crowding these many people into particularly ambitious compositions.

These Flemish-style paintings—Flemish in terms of their genre subjects and their interest in landscape—were extremely popular in the North in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, among both artists and collectors. In eighteenth-century France, their popularity continued strong among both genre painters and collectors. The descriptions of such paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Younger and his collaborators at auction in the rococo are telling in the way that they focus on the individual characters, enumerating their activities, even counting them. This echoes the delight that existed when they were first painted, and the many such pictures by Pater, Quillard, and other artists within Watteau‘s circle demonstrate their continued popularity. Tellingly, copies after Bonaventure de Bar’s variation after Watteau’s Mariée de village were paired with copies after Watteau’s composition. Their relation was understood.

Another noticeable aspect of Watteau’s picture is its explicitly italianate landscape. The large umbrella pine trees dominating the foreground are more evident here than in any other Watteau painting. It draws attention to itself. Certainly the artist‘s contemporaries would have been well aware that this was not a species of tree found in Paris and the Île de France. Equally important is the architectural environment, especially the domed and pedimented church. It has caught the eye of all critics writing about the painting. Some have described it alternatively as analogous to the Pantheon, the facade of a Palladian church, or a theatrical backdrop.

Attributed to Louis Jean François Lagrenée, Landscape with Sant’Andrea in via Flaminia, red chalk, 23.3 x 35.6 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, département des arts graphiques.

Whatever their proposed identifications of the buildings in Mariée de village, scholars did not consider the possibility that this was an actual site in Italy, especially because Watteau had never been able to make the trip to Rome. The building in question proves to be Giacomo Vignola’s mid-sixteenth century church of Sant’Andrea in via Flaminia. It was a note-worthy site that was often recorded in drawings and paintings by visitors to the Eternal City. Particularly germane in establishing the identity of the site is a drawing attributed to Louis Jean François Lagrenée that shows the buildings that Watteau depicted, and from essentially the same point of view on the Tiber river bank. Also important is the large, plain building in the foreground,with a round window under the roof. Likewise, the umbrella pine trees are useful geographical markers. Although still standing today, some of the subsidiary building are gone but Vignola‘s church remains essentially unchanged. Undoubtedly Watteau must have had access to a drawing that depicted this site, one like the study attributed to Lagrenée, but not that very drawing. That was executed several decades after Watteau’s painting.

The dating of La Mariée de village, like the dating of so many of Watteau‘s paintings, remains problematic. When shown in Paris in 1963 it was dated c. 1709. Adhémar placed it c. 1710-11. Mathey, Banks, as well as Macchia and Montagni, assigned it to 1710. Roland Michel, Temperini, and Glorieux ventured to a still later date of 1710-12. Rosenberg and Prat’s position on the date of the painting is, at best, confused. For the greater part, they accept a date of 1710-11 for most of the related drawings, except for the study in Dublin which they place c. 1713. More startling, they would date the Washington compositional drawing to c. 1710, even though it postdates all the preliminary studies from the model as well as the painting itself. Lastly, Posner theorized that the painting was executed over a period of several years, from 1712 to around 1714-1715.

For copies of La Mariée de village, CLICK HERE