- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

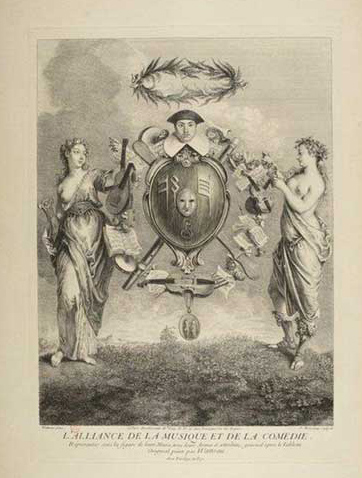

L’Alliance de la musique et de la comédie

Entered August 2014; revised October 2020

Whereabouts unknown

Oil on canvas

64.7 x 54 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Allegoria dell'unione fra Commedia et Musica

Allegorie: Bündnis von Musik und Komödie.

L’Alliance de la comédie et de la musique

The Alliance of Music and Comedy

The Alliance of the Theaters of Paris

The Union of Comedy and Music

RELATED PRINTS

The painting was engraved in reverse by Jean Moyreau for the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé. The print was first announced in the March 1730 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 552).

PROVENANCE

The Moyreau engraving offers no indication of the original owner of this picture and there is no trace of the painting in the eighteenth century.

Paris, anonymous sale, January 26-27, 1835, lot 34: "VATTEAU. La musique et la danse personifiée. Tableau d'une couleur chaude et pleine d'harmonie." Although misidentifying the second muse, this previously unrecorded citation marks the reappearance of the painting in the nineteenth century.

Paris, collection of Paul Daniel Saint (1778-1847, miniaturist). His sale, Paris, Hôtel des ventes, May 4-7, 1846, lot 66: “WATTEAU (Antoine) . . . Deux figures allégoriques represéntant la muse de la comédie et celle de la musique; elles sont placées de chaque côté d’un écusson, autour duquel sont allégoriquement groupés des instruments, des livres et des masques. Ce tableau est gravé sous le titre de l’alliance de la comédie et de la musique.” The painting sold for 500 livres according to the annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Rijksbureau vor Kunsthistorische Dokumentatie.

Paris, collection of Paul Barroilhet (1810-1871). His sale, Paris, March 10, 1856, lot 68: “WATTEAU (ANT.) . . . L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comédie. (Gravé.)” The painting sold for 4,000 livres according to the annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie but, in fact, it remained in the Barroilhet collection.

Paris, collection of Paul Barroilhet. His sale, Paris, Hôtel des ventes, April 2-3, 1860, lot 130: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . L’Alliance de la Comédie et de la Musique. H. 63 c. L. 51 c. ” Withdrawn.

Paris, collection of Paul Barroilhet. His sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, March 15-16, 1872, lot 20: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . L’Alliance de la Comédie et de la Musique. A gauche, la Comédie, la tête ornée de pampres, tient un masque à la main; à droite, la Musique, parée de fleurs, tient une lyre; les deux déesses sont debout, de chaque côté d’un cartouche entouré d’instruments divers et surmonté d’une figure de Crispin. Charmante composition gravée par J. Moyreau. Toile, Haut., 63 cent.; larg., 51 cent.” The painting sold for 2,140 francs according to the annotated copy of the sale catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie.

Paris, collection of Eugène Féral (1831-1900, painter, dealer, and expert) by 1875. Edmond de Goncourt referred to the painting as being with Féral in his Catalogue raisonné of 1875.

Paris, collection of Henri Michel-Lévy (1844-1914; artist). His sale, Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, May 12-13, 1919, lot 29: “WATTEAU (JEAN-ANTOINE) . . . L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comédie. Deux jeunes femmes sont debout de chaque côté d’un cartouche. L’une, presque de face, couronnée de fleurs, portant une draperie rose sur une jupe blanche, tient sous le bras gauche une lyre. L’autre, de profile, couronnée de pampres, drapée de soie rose, regard un masque qu’ell tient de ses deux mains. Le cartouche est composé d’un cadre doré présentant, au centre, un masque et des notes de musique. Au-dessus, une tête d’acteur au large col blanc et coiffé d’un feutre noir. Il est entouré de partitions et d’instruments de musique; une clarinette et une batte sont croisées derrière le cartouche. Fond de paysage. Au sommet de la composition, une couronne de lauriers réunis par un ruban rose. Toile. Haut., 65 cent.; large., 53 cent. Gravé par J. Moyreau.” According to two annotated catalogues in the Frick Art Reference Library, the painting was bought by a Monsieur Hoven; they differ on the purchase price, which was recorded at the very different figures of 80,000 and 41,800 francs.

Paris (?), Hoven collection; sale, Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, April 21, 1921, lot 25: “WATTEAU (ANTOINE) . . . L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comédie. Deux jeunes femmes sont debout de chaque côté d’un cartouche, symbolisant la Musique et la Comédie: au-dessus du cartouche, une tête d’acteur. Fond de paysage. Toile. Haut., 65 cent.; larg., 53 cent. La gravure par Moyreau est jointe à ce tableau. Voir la reproduction. Collection H. Michel-Lévy, mai 1919, no 29.” According to an annotated catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, the painting sold for 38,000 francs to the dealer Marius Paulme, but Paulme probably acted as an agent for Wildenstein since that firm’s records indicate that they bought the painting at the Hoven sale.

New York, Wildenstein & Co., from 1921 until 2006.

France (?), a French-American private collection.

New York, Christie’s, January 25, 2012, lot 112: “PROPERTY FROM A FRENCH AMERICAN PRIVATE COLLECTION / JEAN-ANTOINE WATTEAU . . . / The Union of Comedy and Music / oil on canvas / 25½ x 21¼ in. (64.7 x 54 cm.) / $800,000-1,200,000 / £600,000-900,000 / PROVENANCE . . . EXHIBITED . . . LITERATURE…

Even for Watteau, that most ambiguous of artists, The Union of Comedy and Music is an unusually elliptical work, one that is unique in his oeuvre. It was engraved in reverse by Jean Moyreau for the Recueil Jullienne and its publication was announced in the Mercure de France in March 1730. The print provides the painting's title and a brief caption explaining that Comedy and Music are represented in the guise of their Muses, accompanied by their arms and attributes. The owner of the painting is not given.

At the center of the composition, a convex oval escutcheon is magically suspended against the sky, above a grassy landscape that curves to suggest the contour of the earth itself. Surrounded by an elaborate gilded frame, the black background of the shield is ornamented with a mask of comedy and old-fashioned musical notations rendered in gold. Surmounting the escutcheon is the head of either Crispin or Scapin, the scheming valets in black hats and white ruffs who were stock characters in the Comédie Française, and suspended above the whole is a crown composed of two intertwined laurel wreaths, a crown being a traditional reward of the conqueror and laurel signifying artistic glory. Behind the shield is a diagonal cross composed of a Harlequin's slapstick and a transverse flute, and around it floats an elaborate garland of musical scores, fool's heads, and various musical instruments—including a violin, a guitar, a lute, a viola, a French horn, tambourines and pan pipes. From a pink ribbon tied to the bottom of the escutcheon hangs a silver medallion bearing the image of two standing figures; according to Joseph Baillio, they might be Apollo and a muse.

On either side of this remarkable floating apparition stands a beautiful, semi-clad female figure. On the left is Thalia, Muse of Comedy and Pastoral Poetry, who intently examines a rather grotesque actor's mask, the traditional attribute that she holds before her. Crowned with ivy and breasts exposed, Thalia wears a pink, vaguely antique costume with buskins decorated with lions' heads.

On the right, Music is embodied either by Euterpe, Muse of Music and Lyric Poetry, or possibly Terpsichore, Muse of Dance and Song; both carry musical instruments and have their hair garlanded with flowers. Watteau's palette of slate blues, pearl gray and pale rose is exceptionally lovely and refined, and throughout the composition are rough traces of underdrawing evident to the naked eye. (Infrared reflectography, which has proven very useful in revealing the changes in design made by the artist in other paintings, has not yet been performed on the present work.)

Although every element of this unusual composition is rendered with naturalistic, three-dimensional exactitude -- the softly fleshed women, their shimmering, silken drapery, the string instruments and darkened sky just beginning to glow with the break of dawn—its subject matter exists in the realm of symbolism, and can only be understood, to the degree that viewers today can understand it, by interpreting it allegorically. Over the years, various readings of the painting's possible meanings have been offered, some of them excessively ornate and obscure. François Moureau has offered the most convincing explication of Watteau's subject matter, made all the more satisfactory by its comparative simplicity. He sees The Union of Comedy and Music as an allegory of the alliance of the two separate and competing theatrical establishments, the Comédie Française and the Opéra—a dream that these official stages in Paris could work together harmoniously—in which Watteau aims 'a certain derisive wit at the 'serious' genres.' Contemporary viewers of the painting, aware of the increasing' lack of interest on the part of the fashionable public for tragedies and the tragic theatre,' would have interpreted its allegorical allusions in the light of this popular shift in taste. Moureau acknowledges, however, that layers of meaning in a complex painting such as this are most likely permanently lost to us. 'Any analysis of the finer perceptions in the 'comic subjects' of Watteau presupposes a profound acquaintance with the contemporary theatrical world in which he and his contemporaries lived naturally. What appears to us today as 'constructions' with hidden meanings were as easily interpreted by the fashionable world of his time as was a fable by a historical painter.'

Theories abound that Watteau's painting was designed as a signboard for a theatre or a dealer in musical instruments, or as a model for a stage curtain. It is sufficiently anomalous to suggest that it may have been the result of a specific, now untraced, commission. The artist's connections to the theatre were deep and of long standing, and so the painting might well have been made at the request of one of the numerous actors, musicians, or other men (and women) of the theatre with whom Watteau was acquainted. In style and handling it appears to somewhat predate the Crozat Seasons which are documented as having been executed in 1717, and it might be placed around 1715, if not slightly earlier.

Whatever the allusions Watteau was making in The Union of Comedy and Music to the politics of the official theatres in Régence Paris, his painting still fascinates and moves us as an affectionate tribute to the triumph of the noble theatrical arts, which seem in Watteau's painting to stand alone atop the breaking dawn of a new world. At a time when actors were regarded with suspicion and traveling theatrical troupes often operated one step ahead of the law, Watteau's respect for their art and their commitment to it is both admirable and bracing.

To be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Watteau's paintings by Alan Wintermute.”

Sold for $902,500 (plus premium) to a private collector.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Galerie Martinet, Collections d’amateurs (1860), no. 429. (as by Watteau, L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comédie, lent by M. Barroilhet).

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, La Musique et de la danse (1923), cat. 159.

Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Le Théâtre à Paris (1929), cat. 81 (as by Watteau, L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comédie, lent by MM. Wildenstein).

New York, New School, Loan Exhibition (1946), cat. 19 (as by Watteau, L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comedie, lent by Mr. Georges Wildenstein).

New York, Wildenstein, French XVIIIth Century Paintings (1948), cat. 55 (as by Watteau, Alliance of Music and Comedy). Also listed as cat. 47 in French Painting of the Eighteenth Century, an alternative publication for the exhibition.

Kansas City, Nelson Gallery-Atkings Museum, Century of Mozart (1956), cat. 104 (as by Watteau, The Alliance of Music and Comedy, lent by Wildenstein and Company, Inc.).Zurich, Kunsthaus, Unbekannte Schönheit (1956), cat. 275 (as by Watteau, Allegorie: Bündnis von Musik und Komödie, lent by Galerie Wildenstein, Paris/New York).

London, Royal Academy, France in the Eighteenth Century (1968), cat. 729 (as by Watteau, L’Alliance de la Musique et de la Comédie, lent by a Lausanne private collector [sic for Wildenstein]).

Tokyo, Wildenstein, Masterpieces of European Paintings (1992), cat. 3 (as by Watteau, The Alliance of Music and Comedy).

New York, Wildenstein, Arts of France (2005), cat. 44 (as by Watteau, The Alliance of the Theaters of Paris).

New York, Metropolitan Museum, Watteau, Music, and Theater (2009), cat. 4 (as by Watteau, The Union of Comedy and Music, L’Alliance de la musique et de la comédie, lent by a private collector).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 136.

Thoré-Bürger, “Exposition de tableaux” (1860), 232-33.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 63.

Goncourt, L'Art du dix-huitième siècle (1880), 1: 56.

Fourcaud, “Watteau: peintre d'arabesques” (1908-09), 133-35.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), 130-31.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 24.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 61-63, 260, 3: cat. 39.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 91.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1957), 1: under cat. 136.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 66.

Mirimonde, “Les Sujets musicaux chez Watteau” (1961), 262-63.

Mirimonde, “Statues et emblèmes” (1962), 20.

Eidelberg, Watteau's Drawings (1965), 259, note 59.

Macchia and Montagni, L'opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 123.

Ferré, Watteau (1972): 1, 114; 4: 1007, 1119, 1130; 3: 1058.

Boerlin-Brodbeck, Watteau und das Theater (1973), 167-8.

Mirimonde, L'Iconographie musicale sous les rois Bourbons (1977), 2: 24, note 31.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 161.

Frankfurt, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Einschiffung nach Cythera (1982), 96.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 155.

Washington, Paris, and Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), 489.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), 1: cat. 90.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), cat. 47.

Glorieux, À l'Enseigne de Gersaint (2002), 195, 200.

REMARKS

It is generally agreed that this painting served as some sort of advertisement or signboard for a theatrical company. Although Fourcaud, followed by Adhémar and others, proposed that it might have been destined for a store that sold musical instruments, this is not a prevalent belief. The theatrical masks as well as the head and bust of the comic actor Crispin at the summit of the design argue against such an interpretation. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold suggested that it was painted for the theater run by the widow of Baron, and most recent interpretations have been variants of this basic premise, often with suggestions of different possible troupes. Roland Michel suggested that the picture was a modello for a theater curtain, but the design, especially with the two lateral women, is not particularly well suited for enlargement to monumental scale. Rather, as most critics believe, it seems likely this picture served in its own right as some sort of sign for a theatrical group.

Exaggerated claims have been made for this painting. In the essay written for the 2012 auction catalogue, for example, it was asserted that the painting “is an unusually elliptical work, one that is unique in his oeuvre,” an opinion repeated almost verbatim by Baetjer in 2009. Roland Michel went so far as to claim that this was an example of “a truly allegorical kind of painting unknown and unpracticed at the time Watteau was working.” This is far from true. Allegorical subjects were still fairly common in French art. More important, while allegory was not a predominant element in Watteau’s oeuvre, L’Alliance de la comédie et de la musique is definitely not unique. Allegory is, after all, a common feature of the arabesques that Watteau designed while working for Claude Audran, and it is in the light of those designs that this painting should be understood. Most pertinent is a lost Watteau drawing, colored with gouache or watercolor, that was engraved by Jean Moyreau for the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé under the title Colombine et Arlequin. There are no classical muses in this arabesque, but many of the other elements of the Alliance de la musique et de la comédie are present. At the bottom is an armorial arrangement of a theatrical mask, a fool’s head crossed against a beribboned theatrical sword, and a tambourine. These announce the central motif in L’Alliance: an escutcheon depicting a mask and musical clefs, backed by a bassoon and a comedian’s baton; and they are crossed against each other just as the sword and fool’s head are in the arabesque. Midway up at both sides of Colombine et Arlequin are floral crowns suspended in the air, much like the leafy crown suspended in mid-air in L’Alliance. And at the very top of Colombine et Arlequin, presiding over the whole of the arabesque, is the head of Pierrot, akin to the bust of Crispin placed above the central escutcheon in L’Alliance. In short, Watteau’s early arabesque presages much of the iconography and elements of the compositional scheme found in L’Alliance de musique et de la comédie.

Despite their light-hearted quality, Audran’s and Watteau’s arabesques continued the traditional language of the pagan gods and their attributes. This is predictable since all such artists would have been well versed in this discipline. On the other hand, the attributes in L’Alliance de la musique et de la comédie seem more studied than is normal. A close examination suggests that Watteau employed an iconographical handbook such as Cesare Ripa’s well-known Iconologia, or perhaps one of its French derivatives such as Jean Baudoin’s Iconologie. The muse at the right is Erato, whose name, according to Ripa, signifies love and thus she presides over gentler poetry. Following Ripa’s proscriptions, Watteau shows her holding a lyre in one hand and a plettro (pick) in the other, and she is crowned with myrtle and roses. At the left is Thalia, the muse who presides over comedy and lyric poetry. She has a garland of leaves around her head (Ripa specifies ivy), holds an actor’s mask, and wears buskins, a type of foot covering that was supposedly worn by the ancient comedians—all in accord with Ripa’s instructions. When Moyreau’s engraving was advertised in the Mercure de France, it proclaimed that Musique and Comédie were “répresenté sous la figure de leurs Muses avec leur Armes et attributs,” but critics seem not to have considered how carefully worked out the attributes were. One might wonder if this was Watteau’s doing or whether the patron played a role.

Whereas Mirimonde interpreted Watteau’s painting as representing the coat of arms of the Opéra-Comique, Moureau rejected this because Crispin was a member of the Comédie-Française and masks, such as the one on the escutcheon, were worn by the dancers of the Opéra. So too, the emblems on the shield—musical clefs and scores, as well as the comedian’s baton—correspond to the Parisian Comédie-Française and the Opéra. If the canvas served as some sort of a sign for a theater, this may help explain why there is no record of the work in art auctions until the mid-nineteenth century. It may have bypassed the attention of traditional art collectors, just as the Louvre’s Gilles did.

The thorny issue of dating this work reveals the customary latitude of opinions although most scholars have chosen to ignore the painting altogether. Mathey proposed c. 1707-08, an early date that few would agree with. Adhémar placed it in the period 1712-15. Baetjer opined that while the picture is generally dated around 1715, the “uncertain handling of the nude anatomy” suggests it might have been executed earlier. Yet the joined forces of music and comedy at the Opéra-Comique indicated in the allegory would suggest a date after 1715. Indeed, Roland Michel would date the work to c. 1715-16.