- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

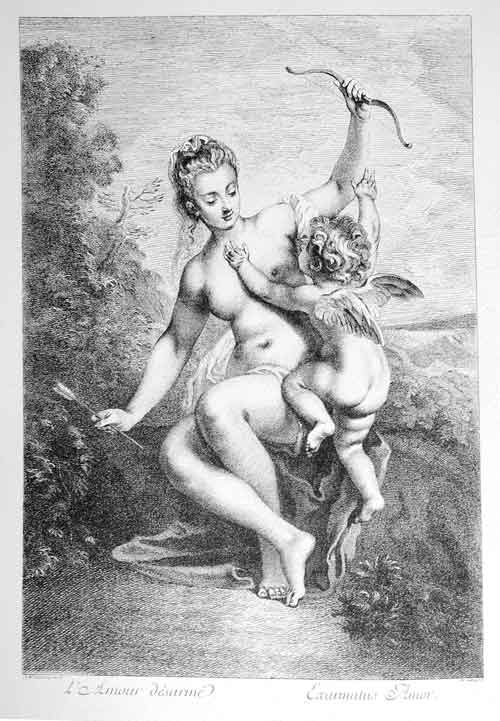

L’Amour désarmé

Entered December 2014; revised October 2024

Chantilly, Musée Condé, inv. PE 369.

Oil on canvas

47 x 38 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Cupid Disarmed

Love Disarm’d

Venus & Cupid

Venus & Cupide

Vénus & l’Amour

Vénus désarmant l’Amour

RELATED PRINTS

The oval painting was engraved in reverse and as a rectangle by Benoît Audran for the Jullienne Oeuvre gravé. The print was executed prior to the end of 1727, and was among those announced for sale in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2677).

In turn, the Audran engraving was copied in London by George Bickham Jr. (1704-1771) under the English and French titles Venus & Cupid; or Love disarm’d and Venus & Cupide; ou L’Amour désarmé, together with the caption “Paul Veronese inv. Watteau pix.” The reference to Veronese and the use of a rectangular format show that Bickham was working directly from Audran’s print and not Watteau’s painting.

PROVENANCE

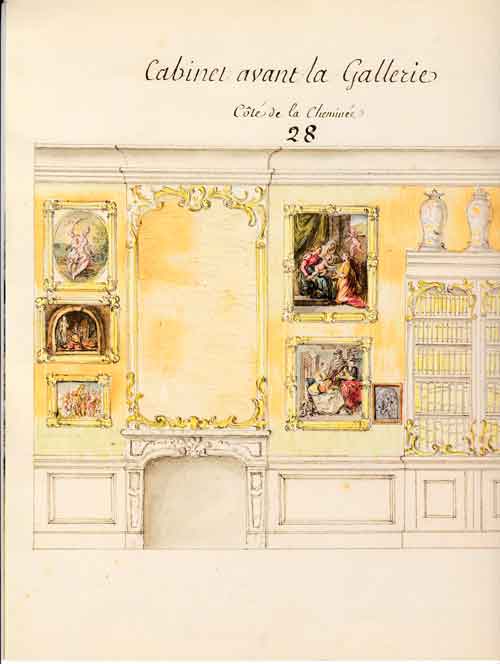

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). Although the name of the painting’s owner is not specified on Audran’s engraving, the picture was listed and illustrated in the manuscript catalogue of Jullienne’s collection, which was prepared before 1756 and is now in the Morgan Library & Museum. It is shown hanging on the wall, to the left side of a mirror above the fireplace, in the “Cabinet avant la Gallerie.” The painting was also listed as no. 1177 in the inventory of the Jullienne collection prepared between March 25 and August 5, 1766. There it again was listed as in the room following an antechamber and before the gallery: “un tableau peint par Watteau, representant Vénus & l’Amour, dans sa bordure dorée, prisé 360 l [livres].”

Paris, sale of the Jean de Jullienne collection, March 30–May 22, 1767, lot 252: “L’Amour désarmé: Tableau sur toile de forme ovale, de 20 pouces de haut, sur 16 pouces 6 lignes de large. B. Audran l’a gravé.” Sold to de Montullé for 499.19 livres according to the annotated copy of the catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie.

Paris, collection of Jean-Baptiste François de Montullé (1721-1787; magistrate). Sale, his collection, Paris, December 22ff, 1783, lot 59: “PAR LE MÊME [ANTOINE WATTEAU] . . . L’intérieur d’un Jardin où l’on voit Vénus désarmant l’Amour; la Déesse est assise sur un banc de gazon couvert d’une draperie rouge. Il vient de la vente de M. de Jullienne, No. 252 du Catalogue. Hauteur 18 pouces, largeur 14 pouces 6 lignes. T. ovale.” Bought for 175.1 livres by the dealer Nicolas Lerouge according to the Getty Provenance Index and the annotated copy in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie.Paris, Hôtel Bullion, sale date unknown (after 1793-94). Bergeret, Lettres d’un artiste, 335, reports that after the Reign of Terror, he and Vivant Denon’s nephew bid each other up on this painting until it reached 45 francs and then it went to a more fervent buyer for another 10 francs, which was considered extraordinary for a painting whose style was then out of fashion.

London, collection of J. F. Tuffen. London, sale, Christie’s, April 2, 1802, lot 7: “Watteax . . . Venus and Cupid, oval.” Bought in. Sale, London, Christie’s, June 18-19, 1802, lot 81: “Watteau . . . Venus disarming Cupid, oval.” Sold for £2. to William Harris or Charles Birch.

London, Peter Coxe, Burrell and Foster, sale, May 7-8, 1805. Collections of Sir John Boyd, Bart and others, lot 33: “Watteau . . . Venus and Cupid—a Study after Corregio.” The cataloguer misidentified the Italian Renaissance master whose work inspired Watteau, probably because he was unaware of the Audran and Bickham engravings, both of which specified Veronese’s influence. Interestingly, the two engravings and Veronese’s were not cited in the previous 1802 sale either. The situation was rectified in the 1829 auction.

London, collection of William Armfield Hobday (1771-1831; portrait miniaturist). His sale, London, Forster, June 19-20, 1829, lot 61: “Venus and Cupid. This Picture has been twice engraved the size of the original. Watteau.” Bought in at £60.18. An error occurred in the compilation of this catalogue and essentially the same text was used for lot 142: “Venus and Cupid. Watteau. Engraved the size of the original.” In the copy of the catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, the printed entry is struck out and replaced by the penned notation “Shetland pony” and with the indecipherable name of a different artist. The allusion to the painting in lot 61 having been “twice engraved” refers to the two prints by Audran and Bickham and reinforces our identification of it as L’Amour désarmé.

London, collection of William Beechey, RA (1753-1839, portraitist). His sale, London, Forster, May 5, 1835, lot 19: “Watteau . . . Venus and Cupid; twice engraved.” Sold for £16.16 to Money according to the Getty Provenance Index.

London, collection of Chevalier Alexandre Antoine Cosson (1769-1867). His sale, London, Christie’s, February 22-23, 1856, lot 95: “Watteau . . . Venus and Cupid—oval. From the ‘Odes of Anacreon.’”

Paris, collection of the marquis de Maison.

Paris and Chantilly, collection of the Henri d’Orléans, duc d’Aumale. The duke bought the painting from the marquis de Maison in 1868; it was transferred in 1886 to the Musée Condé.

EXHIBITIONS

Paris, Alsaciens et Lorrains (1874), cat. 525 (as by Watteau, L’Amour désarmé, lent by the duc d’Aumale).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 15.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 15.

Bergeret, Lettres d’un artiste (1848), 335.

Goncourt, Catalogue (1875), cat. 33.

Gruyer, Notice des peintures (1899), CXIII, no. 369.

Zimmerman, Watteau (1912), pl. 49.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jullienne et les graveurs de Watteau (1921-29), cat. 87.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 9.

Brinckmann, Watteau (1943), fig. 24.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 177.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 68.

Vergnet-Ruiz and Laclotte, Great French Paintings (1965), 71.

Brookner, Watteau (1967), pl. 12.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 124.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. A18.

Chantilly, Peintures célèbrés du Musée Condé (1979), 34.

Ferré, Watteau (1980), cat. p26.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 151, 221, 266, 269, 273.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 79.

Rosenberg, “Une Note sur L’Amour désarmé” (1993), 1-4.

Garnier-Pelle, Chantilly, Musée Condé (1995), cat. 110.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 58, cat. 48.

Hattori, "Montullé" (2010).

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau’s painting was based on a drawing he executed after a Veronese composition that was then in Crozat’s collection and which later was owned by Pierre Jean Mariette before entering the royal collection. Watteau’s copy has not survived but, given his normal practice, its existence can be inferred.

While it was not unusual for Watteau to copy Old Master drawings and then employ his copies when he needed them, it was unusual for him to base an entire picture on such a borrowing. Normally these homages were merely small figures in a larger complex. In this instance, though, Watteau may have been inspired by a second example of Veronese’s art. A closely related painting of this same subject of Cupid and Venus was in Crozat’s collection, similar in composition to the one now in the Worcester Art Museum. This may well have stimulated Watteau to create L’Amour désarmé. However, the obvious differences between the Veronese drawing and the Veronese painting—such as the position of Cupid’s right hand and Venus’ left arm—make it certain that Watteau relied on his copy after the Veronese drawing.

Despite Watteau’s reliance on his study after the Veronese drawing, it was perhaps too generalized for his needs. Thus he may also have had recourse to a sheet of studies now in an Italian private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 635), turning to the charming head at the top left of this page for the head of his Venus.

REMARKS

There has been some confusion about the support of the painting. Gruyer, Zimmerman, Réau, Brinckmann, Adhémar, Macchia and Montagni, and Temperini have all claimed that the painting is on panel, but it is on canvas.

The early nineteenth-century English provenance presented here for L’Amour désarmé is new. Other aspects of the provenance remain unresolved. First Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, then Adhémar, claimed that Boileau père bought the painting at the Jullienne sale in 1767 and that it then sold at “Vente B” in 1778 for 499 francs. However, annotated copies of the Jullienne sale catalogue, such as the one in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Dokumentatie, specify that the Jullienne painting was bought by Montullé. Moreover, it has not proven possible to find a catalogue for a “vente B” in 1778.

Bergeret, Lettres d’un artiste (1848), gives a confused history of this painting’s mid-nineteenth-century provenance. After describing how he and Vivant Denon’s nephew bid unsuccessfully on the picture after the end of the Reign of Terror, in a sale that we have not been able to trace, he then reported that it had come back to Paris, returning from London, and was sold to a rich Englishman for 4,500 francs. None of this is documented, which is a serious fault because some of Bergeret’s other tales are patently false. For example, he claims that he knew a Monsieur Philipot, a curator of paintings at the Academy, who had known Watteau personally and who had described the artist as “un homme charmant, d’un douceur exemplaire.” If this occurred around 1800, as is implied, it would require Philipot to have been born by 1680 and still be alive 120 years later.

There is general agreement that this painting is from the mature portion of Watteau's career, but not the very last years. As inevitably occurs, there is a wide latitude of opinions in assigning a more specific period. Mathey dated the painting as early as c. 1713. Brookner proposed 1714-15. Macchia and Montagni preferred 1715, as did the Chantilly museum’s 1979 catalogue. Adhémar proposed it was from the latter part of 1716, a year to which she assigned an impossibly large number of paintings. Roland Michel favored a date shortly before 1716-17. Posner suggested a wide span of years, between 1713-14 and 1716. As Rosenberg and Prat date the drawing of the head used for L’Amour désarmé to c. 1717-18, they must presume that the painting was executed no earlier than that.

For copies of L’Amour désarmé click here