- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

Assis, auprès de toy

Entered October 2015; revised April 2021

Destroyed

Oil on panel

Measurements unknown

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Le Portrait de Watteau

RELATED PRINTS

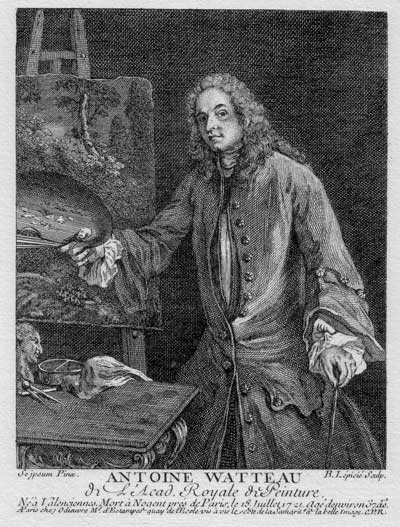

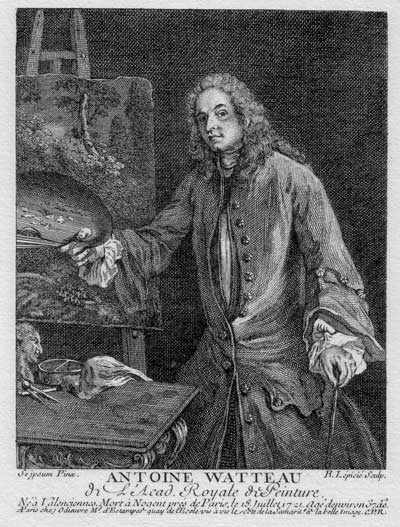

Nicolas Henri Tardieu’s engraving after Assis, au près de toy was executed in the same direction as the painting. It was twice announced for sale, in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure, p. 2676, and in the April 1731 issue, p. 747. Both times it was referred to as Le Portrait de Watteau. At some point between 1731 and 1736, the painted double portrait had deteriorated so badly that it was cut down. Only the central portion containing Watteau’s head, torso, and arms was salvaged, and other parts of the fragment were overpainted. The salvaged section was engraved by François Bernard Lépicié. This second engraving, titled Antoine Watteau, de l’Acad. Royale de Peinture, was advertised in the December 1736 issue of the Mercure, p. 2745. Despite the fragmentary nature of the salvaged painting and its surface, extensively overpainted by a second hand was still declared to be by Watteau. Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold pointed out that this engraving was reissued in Michel Odieuvre’s Portraits des personnes illustres de l’un & l’autre sexe (Paris, 1738) and again in Jean François Dreux du Radier’s L’Europe illustre (Paris, 1765).

There has been a certain confusion about the identity of the second engraver. The print is signed simply “B. Lépicié,” and Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold listed it under this formula. Most modern Watteau scholars have identified the artist as Nicolas Bernard Lépicié (1735-1784), but that cannot be correct since he was only one year old when the print was issued. Rather, the artist must have been his father, François Bernard Lépicié (1698-1755), also an engraver.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). Jullienne's ownership is not acknowledged on the print of Assis, au près de toy nor the two times that the print was announced for sale in the Mercure de France.

The surviving fragment with its modified version of Watteau’s portrait was engraved by François Bernard Lépicié and advertised for sale in December 1736, as discussed above. The cut-down painting showing only the artist was listed in the pre-1756 inventory of Jullienne’s collection, now in the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, under cat. 80: “Portrait de Wateau par . . . Wateau.” Included in the inventory is a carefully drawn watercolor rendering of the wall on which the cut-down Watteau self-portrait hung; it is beneath a large Jacob Jordaens painting of Christ Suffering the Small Children (then attributed to Rubens), and is flanked at both sides by landscapes by Philips Wouvermans, and with pastel heads by François Boucher at the outer edges of the ensemble. In the inventory drawn up in 1766 of the estate of Marie Louise de Brecey, widow of Jean de Jullienne, the two Boucher heads and the modified fragment with Watteau’s portrait were described as hanging in the first room looking onto the first court: “1372 Item trois petits portraits dont celuy de Wateau peint par Luy meme prisés quarante huit livres. . . .”

Paris, sale, Jean de Jullienne collection, March 30–May 22, 1767, lot 256: “Le Portrait de Watteau peint par lui-même; il est à mi-corps tenant sa palette & son appui-main proche d’une table; sur bois, de 5 pouces 6 lignes de haut, sur 4 pouces six lignes de large.” According to the sale catalogue in the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, it sold for 24.1 livres to “Le President De Laisseville.”

Paris, collection of Charles Le Clerc de Lesseville d’Auton (1714-1779; parliamentarian).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 1 and 2.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 1 and 2.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 11 and 14.

Rosenberg, Watteau (1896), 95-96.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 302, cat. 3 .

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), 14, cat. 184.

Alvin-Beaumont, Le Pedigree (1932), 20-27.

Parker, Drawings of Antoine Watteau (1931), 23.

Mathey, “Aspects divers de Watteau dessinateur” (1938), 376.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 67 and 68.

Mathey, “Une Feuille d’études” (1956), 215.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 209.

Cailleux, “Un Portrait de Watteau” (1969), 176.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B35.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 268-69.

Posner, Watteau (1984), 251, n. 4.

Jervis, “Mariette’s Annotated Copies” (1989).

Vidal, Watteau’s Painted Conversations (1992), 158-67.

Börsch-Supan, Watteau (2000), 90.

Michel, Le «célèbre Watteau» (2008)

Kopp and Tonkovich, “The Judgment of a Connoisseur” (2009), 821-24.

Eidelberg, “Assis, auprès de toi” (2011).

Vogtherr and Tonkovich, Jean de Jullienne (2011), 76-79.

Rykner, “Watteau ou pas Watteau?” (2013).

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), cat. 101-03.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Watteau, Study of a Standing Artist Holding his Palette and a Hand Resting on a Mahl Stick, red and white chalk, 26.9 x 17.5 cm. Private collection.

The origin of this double portrait can be traced to two Watteau drawings. The first is a rapid sketch of an artist that is presently in a private collection (Rosenberg and Prat 588). The man’s legs are only quickly indicated; more attention is paid to his jacket. His arm and hand holding the palette and the other hand resting on a mahl stick are more carefully delineated.

Watteau, Sheet of Studies of a Man’s Face, an Actress Standing with her Arm Akimbo, and Two Hands Playing a Viola da Gamba, red and white chalk, 26.9 x 17.5 cm. Los Angeles, Collection of Ariane and Lionel Sauvage.

The second drawing associated with Assis, auprès de toy is a typical Watteau sheet of unrelated motifs (Rosenberg and Prat 625). The upper half has studies of the commedia dell’arte actor and actress used for Les Habits sont italiens, while the bottom part contains the studies of Jean de Jullienne’s hands playing the viola da gamba that were used for the painting.

In both instances, the drawings are in the same direction as the Tardieu engraving, demonstrating that the engraving was made to mirror the direction of the painting.

Anonymous artist after Watteau, Portrait of Watteau, red, black, and white chalk. Chantilly, Musée Condé.

François Boucher after Watteau, Portrait of Antoine Watteau, etching, Figures de différents caractères, plate 1.

François de Troy, Portrait of Jean de Jullienne (detail), 1722, oil on canvas, 92.5 x 73 cm. Valenciennes, Musée des beaux-arts.

A third drawing is related to the development of Assis, au près de toy, but it is highly problematic. It is a half-length self-portrait by Watteau that is known through a version in red, black, and white chalk in the Musée Condé, Chantilly. Watteau’s original drawing is also recorded in an etching by François Boucher that served as the frontispiece for the Figures de différents caractères. As can be seen, this self-portrait largely corresponds to the upper half of Watteau’s figure in Assis, au près de toy, save that the artist’s costume is different. The Chantilly drawing and the Boucher etching are fraught with problems. Whereas in the past the Chantilly drawing was thought to be by Watteau, its autograph nature has been challenged by most scholars for the last few decades. Some have claimed it to be a copy by Boucher made in preparation for his etching. Alastair Laing has rejected that attribution and instead has proposed that it was by Jean de Jullienne, yet there is no proof that Jullienne was a draftsman, much less one so accomplished. On the other hand, Jullienne must have owned this drawing, because he is shown holding it in the portrait François de Troy painted of him in 1722. Equally problematic, Boucher’s etching is captioned “Watteau pinxit” rather than the customary “delineavit.” Why was it claimed to be after a painted model? (And why would a painted portrait be chosen as the frontispiece for two volumes of engravings after drawings?) The Chantilly drawing and the drawing recorded in de Troy’s portrait of Jullienne argue that it was a standard trois crayons drawing. It should be noted that de Troy’s portrait was painted just a year after Watteau’s death. In its way, it echoes the image of the two friends together that was established in Assis, au près de toy.

What role did this third drawing play in relation to Assis, auprès de toy? All figure drawings need not be preliminary to painted portraits. It is conceivable that after painting the double portrait, Watteau was inspired or asked to make a drawing of just his features, and he gave this to Jullienne as a gift. There is little to suggest that the lost drawing was done from life. It is a highly finished, well-composed study in itself. The way that it is composed within a rectangular format suggests that it is an end in itself, an intentionally finished drawing rather than an impromptu study drawn from life with the aid of a mirror.

REMARKS

How did this double portrait of Watteau and his close friend and patron come into being? Did Watteau make it spontaneously as a gift for his friend or did Jean de Jullienne commission it from the artist?

The poem beneath the image deals less with Watteau’s portrait than with its function as the frontispiece to Jullienne’s Oeuvre gravé. The six lines declare Jullienne’s fidelity to his friend and his art:

Assis, au près de toy, sous ces charmans Ombrages,

Du temps, mon cher Watteau, je crains peu les outrages;

Trop heureux! Si les traits, d'un fidelle Burin,

En multipliant tes Ouvrages;

Instruisoient l'Univers des sinceres hommages

Que je rends à ton Art divin!Seated near you, in this delightful shade,

My dear Watteau, I hardly fear the ravages of time,

I am only too happy if the marks of a faithful burin,

In multiplying your works,

Can instruct the world of the sincere homage

That I render to your divine art!

This double portrait suggests the physical and spiritual closeness of the two men, the pleasures of the visual and aural arts, and the inspirational beauty of nature. What wonderful foresight prompted the two men to record their friendship. And what genius (as well as self-promotion) on the part of Jullienne to choose this image as the frontispiece to the Oeuvre gravé.

Assis, auprès de toy was considered a fundamental work within Watteau’s oeuvre until Dacier and Vuaflart proposed that the painting had never existed. They were troubled by its lack of documentation: it was not listed in the manuscript inventory of Jullienne’s collection, now in the Morgan Library & Museum, and it did not appear in the 1767 sale of his collection. Its absence from these two important documents, they cleverly argued, was because the double portrait had never actually existed. Thus the scholars proposed that Jullienne had commissioned Tardieu to create the image as a frontispiece to the Oeuvre gravé. According to them, Tardieu started with the small self-portrait engraved by Lépicié, filled it out with a fuller figure of the artist, added the figure of Jullienne playing the cello, and created the garden setting.

Dacier and Vuaflart’s proposal gained traction and was repeated by many subsequent Watteau scholars including Réau and Adhémar. Macchia and Montagni presented the composition in their catalogue of Watteau’s paintings, but in an ambiguous argument they seemed to follow Dacier and Vuaflart’s reasoning. Roland Michel opined that it was almost certain that Assis, auprès de toi never existed. Donald Posner wrote that he would like to believe that Watteau painted such a work, but he was disturbed by the arguments against it. Vidal accepted the idea that the portraits engraved by Tardieu and Lépicié were likely “pastiches commissioned or personally designed by Jullienne." The same position was taken by Helmut Börsch-Supan, and Christian Michel unhesitatingly rejected Assis, auprès de toi, claiming it was Jullienne’s fabrication.

Curiously, Dacier and Vuaflart knew the study of Jullienne’s hands playing the cello, but this did not cause them to rethink their argument. Parker noted this drawing’s relation to Assis, auprès de toi, but did not allude to the problematic nature of the double portrait. Dacier and Vuaflart were unaware that there was a second drawing, the one showing Watteau standing. When Jacques Mathey published it in 1938, he simply proposed that it was used for both Assis, auprès de toi and for Lépicié’s half-length portrait; he did not try to reconcile it with Dacier and Vuaflart’s arguments. Parker and Mathey accepted both drawings with little surprise, even though they were aware of Dacier and Vuaflart’s theory. So too, Cailleux accepted the authenticity of the double portrait because of the drawings. Likewise, Rosenberg and Prat noted the relationship of the two drawings to Assis, auprès de toi, seemingly unmindful that it had been challenged by so many scholars. In these instances, it is as though scholars opened one eye or the other, but not both.

More important, everyone overlooked a remark by Mariette about the painting, a statement that not only proved the autograph nature of the double portrait but also explained what happened to it. Apparently, when the painting was engraved in 1731, just a decade after Watteau’s death, it was still in relatively good condition. Then it deteriorated so badly that by 1736 it had been cut down and only the central portion containing Watteau’s head, torso, and arms was saved. This fragment, with its background painted over and the table in the foreground added, was engraved by Lépicié in 1736. When the overpainted fragment was sold with the Jullienne collection in 1767, Mariette annotated his copy of the sale catalogue, now in the National Art Library, London, with the invaluable note: “Il est dans un état déplorable. Ce sont les debris d’une plus grande composition dont on a l’estampe on y voyoit le peintre accompagné de Mr de Jullienne jouant de la basse de Viole.” The accuracy of Mariette’s remarks should not be questioned. As was recently noted by Kopp and Tonkovich, “Remarkably clear and concise, Mariette’s judgments are distinctly frank and incisive. . . . Mariette’s wording is always sensitive, usually measured but sometimes outright passionate. . . . The connoisseur’s marginalia on the pages of the Jullienne sale catalogue are therefore central to anyone interested in the art world in France before the Revolution.”

Despite my presentation of much of this evidence in 2011, there has been considerable resistance, both from those who claimed the painting had never existed and from those who claimed that the double portrait was still extant. Vogtherr, for example, continued to deny that Watteau ever painted the double portrait, although at the same time he presented Watteau’s two preliminary drawings. Likewise, Raymond supported the idea that the double portrait was a posthumous invention. On the other hand, when a well-known version of the double portrait came up for sale in Paris in 2013 (our copy 2), it was claimed to be the original from Watteau’s hand.

For copies of Assis, au près de toy click here