- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

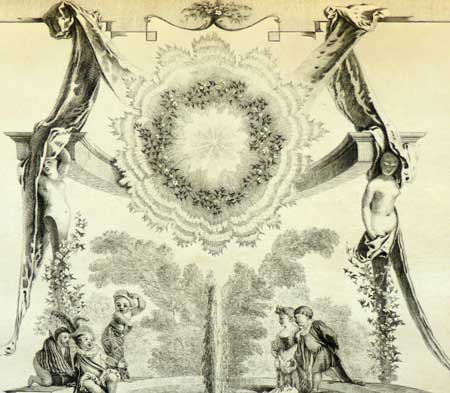

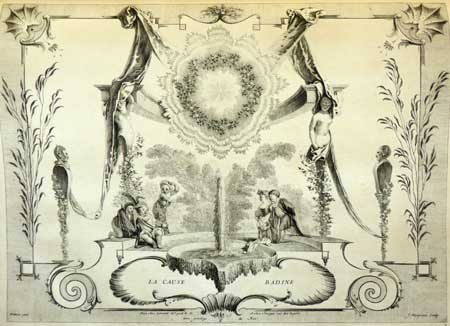

La Cause Badine

Entered June 2017; revised February 2022

Presumed lost

Materials unknown

Measurements unknown

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Composizione con bimbi vestiti da maschere della commedia dell’arte

RELATED PRINTS

Jean Moyreau after Watteau, La Cause badine, engraving, c.1729

This decorative design and its pendant, Les Enfants de Momus, were engraved by Jean Moyreau in 1729. They were announced for sale in the April 1729 issue of Le Mercure (p. 751).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIe siècle (1860), 59.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 291.

Fourcaud, “Watteau: Peintre d'arabesques” (1908-09) ,

Deshairs, “Les Arabesques de Watteau” (1913), 294.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), cat. 119, p. 59.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 273.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 115.

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 46.

Parker and Mathey, Watteau, son oeuvre dessiné (1960), 1: cat. 195.

Montagni and Macchia, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 20.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 9.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 283.

Grasselli, “Eighteen Drawings by Watteau” (1993, n. 13.

Rosenberg and Prat, Watteau, catalogue raisonné des dessins (1996), cat. 154.

Eidelberg, “How Watteau Designed His Arabesques” (2003), 69-71.

Brussels, Palais des beaux-arts, Watteau, Leçon de musique (2013), under cat. 26.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Although a substantial number of Watteau’s studies for arabesques are extant, few can be directly related to the artist’s known compositions. Yet there is a drawing, now in the Horvitz Collection, that is directly connected to La Cause badine and its pendant, Les Enfants de Momus (Rosenberg and Prat 154). Typical of the way that Watteau and other decorative designers worked, the artist sketched only half—the left side—of the overall composition. This was a time-saving convention that decorative designers often employed. He indicated the basic scheme of a female herm, with foliage below and an upraised arm looped in a swag of drapery. Above this is a strong but relatively simple entablature that curves inward to the center. As architecturally solid as the entablature may seem, it floats in the air, unsupported by columns. Finally, at the top of the composition is a wreath-like device centered on a woman’s head. The Horvitz Collection drawing is cut at the top; otherwise there might be additional correspondences in the upper region as well.

A century ago, Louis de Fourcaud rightly recognized that this drawing served for the Watteau arabesque Le Galan, a composition that has much in common with La Cause badine and Les Enfants de Momus. This relationship was repeated by Deshairs, but when Parker and Mathey, and then Rosenberg and Prat, included this drawing in their respective catalogues, they somehow overlooked this important observation. More surprising, Grasselli seems to have cast doubt on this study. Curiously, until 2003, no one had realized the drawing was also associated with our two arabesques as well.

In truth, the Horvitz Collection drawing is more closely related to Les Enfants de Momus but even so, a few of its elements are pertinent to La Cause badine: the female herm with foliage below, the curving entablature, and the general idea of a central wreath at top.

Watteau, Children Comedians Parodying a Military Procession (detail), red chalk. San Francisco, collection of Mrs. John Jay Ide.

This leaves unresolved the issue of the child actors at the center of the composition. Although no specific preparatory drawing for La Cause badine is known, there are a group of early Watteau compositional drawings with children that register his interest in this theme. One, a drawing of nude children and some wearing commedia dell’arte costumes (Rosenberg Prat 13), parodies a military procession and it suggests the sort of drawing that Watteau might have relied on for his arabesque.

REMARKS

In large part, this arabesque and its pendant have not been considered in detail by Watteau scholars.

When Gersaint announced that the Moyreau engraving after La Cause badine was ready for sale in 1729, he described it as “une espèce de plaidoyer fait par des petits enfants qui se disputent,” that is, he saw it as a scene in which the children dressed in commedia dell’arte costumes were divided into two disputing groups: at the right Crispin speaks on behalf of the woman at his side, gesturing as an orator to his fellow actors on the opposite side, who include Harlequin, Mezzetin, and Biscegliese. In a limited way, then, this composition can be related to Gillot’s drawing in the Louvre of a scene of the commedia dell’arte in which an actress pleads a case before the other actors of the troupe.

The engraving states “Watteau pinx.,” but was Moyreau copying an actual, full-size arabesque painted in oil on canvas, presumably meant to function as an overdoor or overwindow? Or was he copying a small preparatory watercolor or gouache?

As for the date of the arabesque, Montagni and Macchia as well as Roland Michel posited 1706-08, whereas Rosenberg and Prat suggested c. 1712 for the Horvitz drawing, which would establish a terminus post quem for the painted arabesques. Adhémar thought that it was executed in mid-1716 (a period to which she assigned more than fifty works). The marked disagreement among these authors is extreme. Presumably the earlier date was proposed on the assumption that Watteau painted such decorative works only in his early career.

For copies of La Cause Badine CLICK HERE