- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

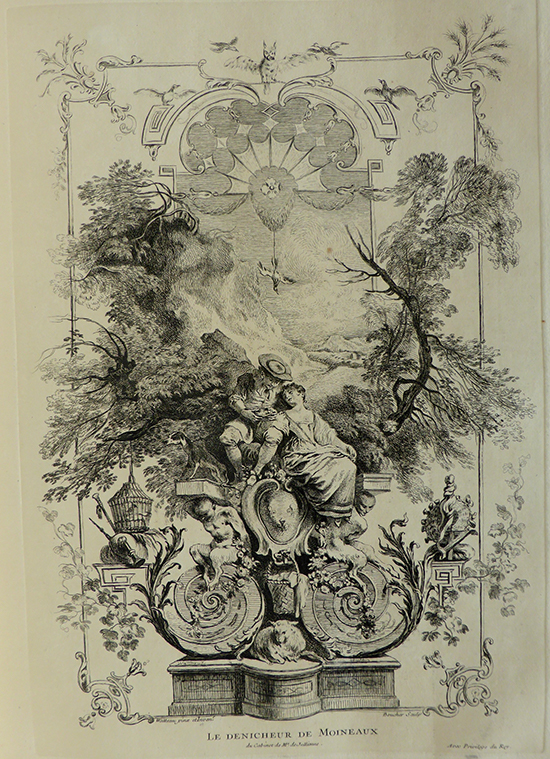

Le Dénicheur de moineaux

Entered March 2020; revised April 2021

Edinburgh, Scottish National Gallery, inv. no. NG 370. 1860

Oil on paper, glued on canvas mounted on wood panel

23.2 x 18.7 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

French Pastoral

The Nest Robber

Pastoral

La Pastorale française

The Plunderer of the Sparrow’s Nest

Der Plunderer des Sperlingsnestes

The Robber of the Sparrow’s Nest

RELATED PRINTS

François Boucher after Watteau, Le Dénicheur de moineaux, engraving, c.1727.

Watteau’s arabesque Le Dénicheur de moineaux was engraved in the opposite sense by François Boucher in 1727. It was announced for sale in the December 1727 issue of the Mercure de France, p. 2677.

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne. His sale, March 30, 1767, lot 255: “Un Tableau d’Arabesques avec deux figures, peint sur toile, de 14 pouces de haut, sur 9 pouces 6 lignes de large. M. Boucher en a gravé une estampe de goût, sous l’inscription du Dénicheur de moineaux.” According to an annotated sale catalogue in the Bibliothèque nationale, the painting sold for 175 livres to Charles Le Clerc de Laisseville.

Paris, sale, Giroux, 1816, cat. 423. This sale catalogue is referred to by Edmond de Goncourt, but it has not been possible to locate such a catalogue, much less verify that the picture in this sale was Watteau’s actual painting.

Edinburgh, collection of Hugh William Williams (1773-1829; painter). By descent to his widow, Mrs. Hugh William Williams (née Robina Miller). Donated to the National Gallery of Scotland in 1860.

EXHIBITIONS

London, Grafton Galleries, National Loan Exhibition (1909), cat. 17 (Watteau, French Pastoral, lent by the National Gallery of Scotland).

London, Royal Academy, Landscape in French Art (1949), cat. 101 (Watteau, Pastoral, lent by the National Gallery of Scotland).

Edinburgh, National Galleries, Scottish Treasures (2001), cat. 25 (Watteau, The Robber of the Sparrow’s Nest).

Botticelli to Braque: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland (2015).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 270.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 28.

Phillips, Watteau (1895), 16-17.

Dilke, French Painters of the XVIII Century (1899), 85.

Phillips, “Imperial German Pavilion” (1901), 362.

Josz, Watteau (1903), 83.

Foster, French Art from Watteau to Prud’hon (1905), 1: 105-06.

Gibb, Catalogue of the National Gallery of Scotland (1906), cat. 59.

Fourcaud, “Watteau, peintre d’arabesques”

Nicolle, “Exposition nationale de maîtres anciens” (1910), 60.

Zimmermann, Watteau (1912), no. 42.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 259; 2: 25, 61, 83, 97, 99, 101, 132- 33, 150, 159; 3: cat. 5, under cat. 10.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 261.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 86.

Moussaili “L’Enchantement de Watteau” (1958).

Mathey, Watteau, peintures réapparues (1959), 67.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 71.

Ferré, Watteau, 1972, cat. B. 84.

Banks, Watteau and the North (1977), 221.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 101.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 213, 269, 281-83, 304.

Le Coat, “Watteau et l’imaginaire social” (1987), 181.

Temperini, Watteau (2002), 37, cat. 19.

Michel, Le «Célèbre» Watteau (2008), 131.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 139.

Tillerot, “Engraving Watteau” (2011 ), 43, 49 n.17.

Ziskin, Sheltering Art (2012), 171, 198.

RELATED DRAWINGS

There are no drawings associated with Le Dénicheur de moineaux.

REMARKS

Although arabesques form an important part of Watteau’s oeuvre, Le Dénicheur de moineaux is one of the few extant examples he actually painted. The others are L’Enjoleur and Le Faune in Valenciennes, and L’Escarpolette in Helsinki. However, the Edinburgh picture represents only the central portion of Watteau’s original design, the whole of which is recorded in Boucher’s engraving. Just the figural elements were kept, and the background was painted over to hide the portion of the garland that remained. A similar disfiguration occurred in regard to the arabesque in Helsinki. Le Dénicheur de moineaux was apparently cut down some time before it was auctioned in 1816. This was noted by Edmond de Goncourt, who referred imprecisely to a sale that listed the reduced measurements; however, it has been impossible to trace that sale. Even when whole, Le Dénicheur de moineaux had been a relatively small picture, measuring approximately 37.8 x 25.7 cm. The arabesques in Valenciennes are much larger, measuring 79.5 and 87 cm in height, and 29 cm in width essentially twice as high as the Edinburgh picture. The Helsinki canvas is still larger, at 86 x 73 cm, and that is only half the size of the original arabesque.

Also remarkable is the medium of the Edinburgh painting: oil paint on paper. This is unusual but not unheard of within Watteau’s oeuvre. The landscape Bièvre à Gentilly is also an oil study on paper. Significantly, another decorative design by our artist, Colombine et Arlequin, was painted in gouache or watercolor on paper. Some of the same questions about the latter composition also are central to our understanding of Le Dénicheur de moineaux. Was the paper laid on canvas originally, or was it strengthened this way later, when Jullienne owned it? Without support, the paper would probably have been too fragile to allow its display as some sort of sign (as some critics have theorized), even if just placed in a window. Were Watteau’s paintings on paper modellos for larger works?

Fourcaud noted the presence of three fleur de lys on the shield at the bottom center of the design, and suggested it was a sign for Sirois’ shop, which was named “Aux armes de France.” It is a clever but not altogether satisfying proposal about the design’s destination.

Because the sky was overpainted to minimize the decorative festoon at the top, some scholars did not recognize the Edinburgh picture as an autograph Watteau. Adhémar grasped the idea that the original composition was much larger but not that the Edinburgh picture had been cut down, wrongly concluding that it was a copy in reduced form. She described Watteau’s arabesque as lost, but noted that the central part was in the National Gallery of Scotland. Similarly, Mathey thought that the painting in Edinburgh was not the original but a replica. Ferré and Saint Paulien were also caught in this confusion, listing the Edinburgh painting as attributed to Watteau, but also calling it a “pastiche grossier” based on the Boucher engraving.

The provenance of the painting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is problematic. After it appeared in the 1767 Jullienne sale it disappeared from sight. According to Goncourt, it reappeared in the 1816 Giroux sale, but so far it has proven impossible to locate a copy of that sale catalogue. Reference is often made to paintings sold in Paris auctions in 1834, 1835, and 1850, but these works, both with similar titles, are unrelated to the original work by Watteau and are catalogued separately; see X.Le Dénicheur de moineaux and X.Les Dénicheurs d’oiseaux. The Edinburgh painting was donated by Robina Miller Williams in 1860 or 1866, but if it was originally bought by her late husband, Hugh William Williams, who died in 1829, this would push the painting’s history back to the early nineteenth century.

When was Watteau’s painting executed? Mathey dated it to 1709. Macchia and Montagni suggested 1710. Adhémar proposed 1712. Temperini and Glorieux opted for 1709- 12. While Roland Michel at first preferred 1710-12, she later claimed it was not painted before 1715-16. This late dating is not one most scholars would accept.

Watteau, Le Dénicheur de moineaux (detail).

Peter Paul Rubens, The Birth of Louis XIII (detail). Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Moussaili proposed that the posture of the woman in Le Dénicheur de moineaux was based on Rubens’ figure of Marie de Medici in the Birth of Louis XIII. Although this is a clever aperçu, it does not hold up: the similarities are more fortuitous than intentional. Rubens posed his woman in a complex contrapposto, her torso and legs turning in opposite directions, while Watteau posed his model rather straightforwardly. Rubens’s woman locks one foot against the other at the heel, a pose derived from Michelangelo and Annibale Carracci, but Watteau points his lady’s dainty feet downward. The languor expressed by Marie de Medici as she gazes at her newborn son is quite different from the perky attitude of Watteau’s young woman. But even if improbable, Moussaili’s idea has found a few adherents, notably Banks and Temperini.

Click here for copies of Le Dénicheur de moineaux